PARC, NPS Since its sighting by Spanish navigators in 1769, the San Francisco Bay has been the site of countless shipwrecks. The infamously difficult sailing conditions off the Golden Gate must be navigated using great caution, experience, and sometimes luck. For many unfortunate ships the waters of the Bay became a final resting place. Some made their way in pieces to the sands of Ocean Beach. Ships that were more fortunate were rescued and survived to continue sailing. To learn more about the history of shipwrecks near Lands End, please expore the following narratives:

The Wreck of AberdeenThe steam schooner Aberdeen was built in Aberdeen, Washington in 1899 for the Pacific Lumber Company to carry passengers and lumber up and down the Pacific Coast. In 1911 Aberdeen was sold. Her new use was to haul garbage from Oakland and dump it off at the Farallones. Aberdeen and her sister ship, Signal, made the trip through the Golden Gate three times a week.In 1913 Signal, along with several of her crew were lost in heavy seas. Aberdeen met a similar fate in 1916 on her way back from the Farallones. Rough seas and a 95 mile per hour gale capsized the schooner, breaking it in two. Over the next few days pieces of the vessel washed ashore along Ocean Beach from the Cliff House to Sloat Blvd. All eight members of the crew met their deaths in the wreck.

The Wreck of Frank H. BuckBuilt in 1914 for the Associated Oil Company of California, the Frank H. Buck was named for the company’s vice-president. Frank H. Buck traveled between New York, Europe, Central America and Asia carrying bulk cargo for the petroleum industry. When World War I broke out, Frank H. Buck was requisitioned by the Navy as an oiler and fitted with a 6-inch and a 4-inch gun. The tanker put her guns to use, exchanging fire with a German U-boat and sinking another surfaced U-boat that had opened fire on the tanker.After the war Frank H. Buck was returned to her owners and continued service as an oil tanker. On March 6, 1937 the Frank H. Buck was on her way through the Golden Gate, bound for Martinez with a cargo of oil from Ventura when it crashed head-on into the luxury passenger liner, President Coolidge. Fog at the Gate had prevented the ships from seeing each other and warning signals were heard too late to avoid the collision. The President Coolidge was one of the two largest American passenger vessels at the time. It merely suffered a crushed bow. But the Frank H. Buck was fatally wounded. Quick responses by the Coast Guard and the San Francisco Police Department saved all of the crew, including the ship’s dog. The remains of the Frank H. Buck came to rest in the sand and rocks off Lands End, next to its sister ship, the Lyman Stewart, which had met a similar fate 15 years earlier. In 1938 the ship’s remains were dynamited as part of a general effort to clean up some of the many shipwreck hulks that littered the harbor approach. Today the engine and sternpost can still be seen at low tide, resting next to the engine of the Lyman Stewart.

The Wreck of King PhilipThis clipper ship built in Maine in 1856 transported trade goods between Boston, Europe, South America, and the Pacific coast. An 1869 mutiny in Honolulu left the ship seriously damaged by a fire set by a crew member.The damaged vessel was sold to a San Francisco lumber merchant who repaired and put her to work shipping guano and grain to Europe. In 1874 the ship was set on fire by yet another mutinous crew in Maryland. King Philip survived the fire and was re-rigged for the Pacific Coast lumber trade. In January 1878 King Philip and Western Shore were being assisted out the Golden Gate by a steam tug. The captain of Western Shore was fatally injured. The tug let go of King Philip to assist the other ship. King Philip dropped anchor, but the seas were heavy and rolled the ship, stranding it on Ocean Beach at high tide. When the tide receded the ship was dry and high enough for spectators to walk up and touch her hull. The hulk was sold to John Molloy who cut away the masts and used explosives to salvage metal and timber. The lower portions of the bark still lie buried beneath the sand, occasionally made visible by a heavy storm or low tides.

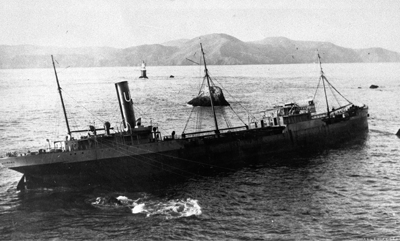

The Wreck of Lyman A. StewartNamed after the president and one of the founders of the Union Oil Company, the Lyman A. Stewart was built by Union Iron Works in San Francisco in 1914. Though identical to its sister ship, the steel-hulled oil tanker, Frank H. Buck, the Lyman A. Stewart’s career along the West Coast was far less adventurous until 7 October 1922.Lyman A. Stewart left San Francisco Bay on a routine trip to Seattle with a cargo of oil. As she left the harbor in thickening fog and a powerful current, the freighter Walter A. Luckenbach was headed in through the Golden Gate. Horns and whistles were muffled in the thick fog and neither vessel saw the other until it was too late. The Lyman A. Stewart’s port bow suffered a deep cut in the collision and began to sink. Captain Cloyd ordered his crew to abandon ship while he stayed on the tanker to steer her to shore. The vessel ripped her hull on the jagged rocks of Lands End where she stayed grounded despite strenuous salvage efforts. Powerful ocean waves eventually pushed Lyman A. Stewart further up on the rocks and she broke in two. Fifteen years later, Lyman A. Stewart’s sister ship Frank H. Buck would meet a similar fate in the same spot. In 1938 both wrecks were dynamited in an attempt to clean up wrecks in the harbor. The engine block of Lyman A. Stewart and the engine and sternpost of Frank H. Buck can still be seen today at low tide

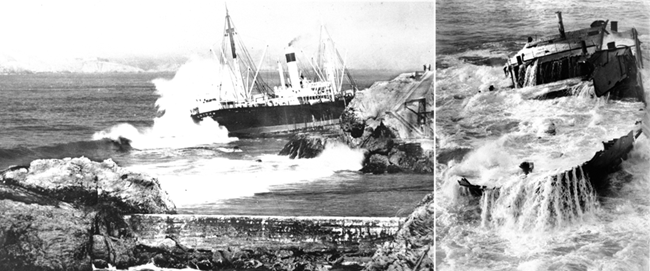

The Wreck of OhioanThe freighter Ohioan was built for the American-Hawaiian Steamship Company of Maryland in 1914. The Company was one of the most important shipping firms of the early 20th century, owning the largest single fleet of American freighters. Ohioan was a part of the Company’s attempt to double its size between 1910 and 1915.Ohioan worked on the Atlantic for the first six years of her career, including several years with the U.S. military during WWI. After the war, Ohioan began sailing the coast to coast routes through the Panama Canal that she would for the rest of her career. In October 1936 Ohioan was carrying a cargo of washing machines, trucks and general merchandise to San Francisco. She ran aground off Point Lobos after her pilot lost his bearings in the dense fog. The cargo was salveged over the next few months and the wreck remained off Point Lobos until torn apart by a winter storm in 1938. Ohioan’s stern post and boiler can still be seen at low tide

The Wreck of ParallelThe San Francisco-built schooner Parallel served as a “work-a-day” vessel hauling cargo along the Pacific Coast beginning in 1868. On 13 January 1887 Parallel left the Golden Gate headed for Astoria, Oregon with a cargo that included 42 tons of black powder.The ship fought against head winds and a strong tide for two days before Captain Miller ordered the crew to abandon ship near the rocks at Point Lobos. The nine men made it safely to Sausalito while Parallel grounded near the Cliff House at the future site of Sutro Baths. Rescuers from the Life-Saving Station found no crew on board. They posted watchmen and retired for the night, unaware of the ship’s explosive cargo. At 12:34 a.m. on January 16 after hours of being tossed against the rocks, the explosives detonated, demolishing the ship, damaging the Cliff House, and sending debris over one mile in all directions. According to local newspapers, the next morning more than 50,000 people gathered to view the scene of destruction.

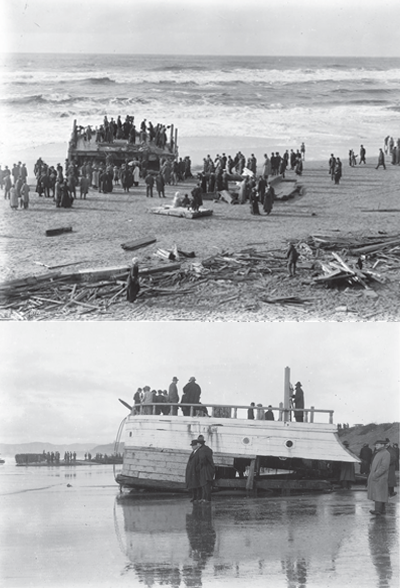

The Wreck of ReporterThe schooner, Reporter was built in Washington in 1876 and spent its years hauling lumber along the Pacific Coast. In early March 1902 Reporter, loaded up with four hundred thousand board feet of lumber, shingles, and shakes, left Grays Harbor bound for San Francisco.Reporter approached the Golden Gate on the foggy evening of March 13. Because of the low visibility, Captain Adolph Hansen mistook a light at the Cliff House for the Point Bonita lighthouse, causing him to steer the ship right into Ocean Beach instead of through the harbor entrance. Fortunately, a surfman of the Golden Gate Life Saving Station saw the ship’s distress signal and the entire crew was saved by the rescuers of the Life-Saving Station. By morning the waves had pushed the remains of Reporter onto the beach about three miles south of Point Lobos, the same spot where King Philip had washed ashore in 1878. Thousands of spectators came to the beach to view the wreck, which gradually fell apart and disappeared beneath the sand.

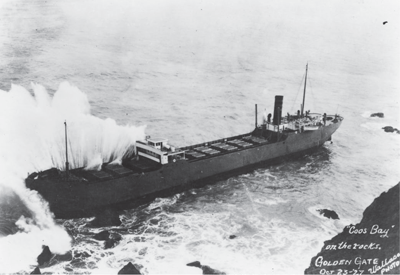

The Wreck of Coos BayOriginally named Vulcan, the Coos Bay was built in 1909 in Maryland. Vulcan was owned by the US Navy Department and used to transport coal to vessels along the Eastern Seaboard.By 1924 fuel oil was beginning to replace coal and Vulcan’s services were no longer necessary. She was sold to the Pacific States Lumber Company of Delaware. Renamed Coos Bay, the vessel was enlarged and modernized, carriying lumber from the Northwest to San Francisco and San Pedro. On 22 October 1927 the ship was headed toward Coos Bay, Oregon. As she passed through the Golden Gate the vessel was enveloped in thick fog. No visibility, a strong ebb tide, and a northwesterly swell led the ship far from its path, crashing into the rocks east of China Beach. The hull was destroyed and water flooded the engine room, shutting down the ship’s power. After waiting out a cold night on deck the 33 crew members were eventually rescued by boat and rescue line. For several years the remains of Coos Bay could be seen stuck in the rocks becoming increasingly bent and twisted by the waves. In 1930, after complaints over the unsightly appearance of scattered shipwreck remains in the harbor, the Junior Chamber of Commerce scrapped the vessel. Today, fragments of twisted metal still can be seen at low tide. |

Last updated: May 13, 2022