|

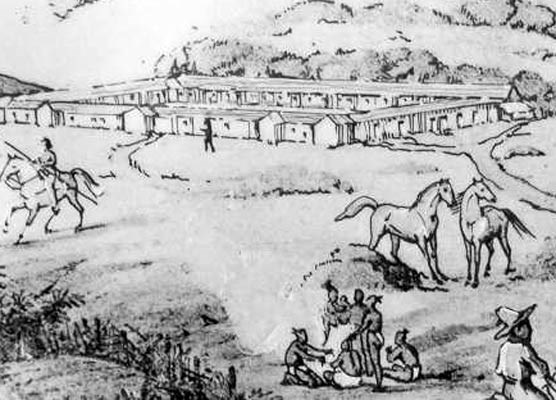

Spanish Era 1776 - 1821 In an effort to solidify their control over North American resources and territory, European colonial powers began to construct fortifications to protect their settlements from foreign encroachment. The Spanish empire had made several claims to California and sought to consolidate its position in North America as a colonial power. Recognizing the significance of San Francisco Bay's vast harbor, Spain began to fortify the area with defensive structures. Construction of the first defensive structure began in 1776. A lightly fortified military outpost, known as El Presidio de San Francisco in Spanish, was built just inside of the Golden Gate to provide protection for the garrisoned soldiers. This fortification and the others to follow were largely constructed using labor provided by indigenous people from the villages and missions of the Santa Clara Valley and San Francisco area. El Presidio was quite vulnerable to foreign attach, considering its lack of armament to defend itself against naval attack. The Spanish were aware of this vulnerability, and the growing tensions in the region would soon prompt them to address their concerns.

Image courtesy of the Bancroft Library, University of California, Berekely, CA In the years following the establishment of the Presidio, Spain and Great Britain contested ownership of the North America Pacific Coast. Both colonial powers attempted to settle their territorial dispute at the Nookta Convention of 1790. However, their efforts to reach an agreement were unsuccessful, and in 1792, the growing tensions between the two colonial powers became evident when British naval officer George Vancouver visited the Presidio of San Francisco and apprised his government of the lack of adequate defenses. In a reaction to this report and a growing concern for British territorial claims on the West Coast, Governor Jose Arrillaga order the construction of a coastal fortification to protect Spain's control of the harbor. In 1793 work began on a land battery to protect the Bay of San Francisco at its narrow entrance. Located on La Punta de Cantil Blanco, or the point where the white bluffs overlook the two-mile wide Golden Gate Straits from the south, an adobe fort with 15 cannon embrasures was completed in December of 1794. The Spanish fort, which became the first coastal defensive structure on the western coast of North America, was named the Castillo de San Joaquin. A report in 1794 states that ordnance for the castillo and post included 800 cannon balls, "30 stands of grapeshot or canister, 52 arrobas and seven ounces of powder, 21 arrobas and 10 ounces of lead foil for wrapping flints, seven arrobas and 24 ounces of musket balls, 3,065 musket Not long after building the Castillo de San Joaquin, Spanish relations with Britain began to deteriorate. The tensions between the two countries eventually erupted into a full-scale war in 1797. The war spread rapidly, and when the conflict reached the small settlement on San Francisco Bay, Governor Diego de Borica ordered an additional battery built two miles to the east of the Castillo, well inside the bay at a point with suitable anchorage (Fort Mason would be built at the same location in the future). First called Bateria San Jose, but later known as Bateria de Yerba Buena after the name of a nearby cove, this outpost was constructed with eight embrasures, yet it was only equipped with five eight-pounder cannons at the time of its completion.

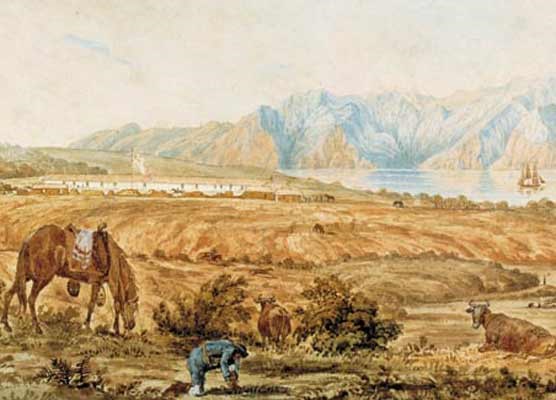

Illustration courtesy of the Mr. and Mrs. Henry S. Dakin Collection Mexican Era, 1822-1846Although Spain had anticipated an attack on the pueblo on San Francisco Bay by the British, that assault was never realized. Ironically, the greatest threat to Spain's control of the region came from an unforeseen enemy which had also been a former ally. The Spanish colony of Mexico embarked on a war for independence in 1821. Following a successful revolt later that year, the Colony won its freedom from Spain. Alta California, which encompasses present-day California, passed quietly into Mexican control. Augmenting the fortification of the San Francisco Bay was a low priority for the new regime, and the defenses at Bateria Yerba Buena soon fell into further disrepair. A U.S. military report issued in 1841 revealed that only one rusty cannon was stationed at the derelict battery, and by 1846 the coastal fortifications at Bateria Yerba Buena were entirely abandoned by the Mexican military forces. At the present time, no remains of this outpost are known to exist. In 1834, General Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo, who was the new comandante of the Presidio, moved part of the San Francisco garrison north to Sonoma. The move was partially precipitated by the dilapidated condition of the Presidio's adobe structures. The damage to the fort's structures, largely as a result of adverse weather conditions, was so severe that the fort needed to be almost entirely rebuilt. However, the Mexican government refused to fund the project and the Presidio continued to deteriorate. By 1835, Vallejo had transported the last of the San Francisco garrison to the new northern outpost in Sonoma, leaving the security of the Presidio in the hands of a few caretakers.1 During the period of Mexican control of California, the increasing prominence in sea commerce and an expanding migration of Anglo-American settlers into the region had aroused the territorial ambitions of the United States. In June of 1846, American settlers, supported by a contingent of indigenous Californians, revolted against the Mexican government of Alta California in a movement known as the Bear Flag Revolt. The United States backed the insurgents, which dispatched a small force to march south from Sonoma. The revolt was led by a Captain of Topographical Engineers, John C. Fremont, and included mountain man Christopher "Kit" Carson. Only meeting light resistance on their march to the pueblo of Yerba Buena, Fremont and his men quickly reached the mouth of the San Francisco Bay, and crossed the harbor at its narrowest point (the Spanish called the entry to the bay Boca del Puerto de San Francisco, but in the following years Fremont used his influence as a topographer to rename the harbor's entrance Chrysoceras or Golden Gate, when translated from Latin into English). When the American force reached the shores of Yerba Buena, the few Mexican soldiers stationed at the Presidio fled at the sight of Fremont's men, leaving the Castillo de San Joaquin and the Presidio effectively abandoned. Just two hours after the Americans landed on Yerba Buena, the entire arsenal of the Castillo, comprised of a number between ten and fourteen cannons, was rendered useless by a process known as "spiking." The final assault on the Presidio came on July 9, 1846, when Captain John B. Montgomery of the U.S. sloop Portsmouth landed a force of marines to seize the settlement of Yerba Buena, which would later become known as San Francisco. At the Castillo de San Joaquin, the marines found three brass guns that they believed to be 12 and 18 pounders, made in 1623, 1628, and 1693. In addition, seven iron guns were found at the Castillo. The bronze guns that were recovered are believed to be the San Pedro, San Domingo, and La Birgen de Barbaneda. These guns are currently on display at the Presidio.

NPS photo Today, the archaeological remains of El Presidio lie buried beneath the Presidio Main Post and inside the walls of the Presidio Officers' Club. Nothing remains of El Castillo or the above ground elements of Bateria de Yerba Buena, but the archaeology remains of the latter are unstudied. To learn more about the early history of the California coast and how the Spanish colonized this area, visit the National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary at Discover our Shared Heritage - Heritage Travel (U.S. National Park Service)

1. Dana, Richard Henry Jr. Two Years Before the Mast: A Personal Narrative. Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1872. |

An official website of the United States government

Here's how you know

Official websites use .gov

A

.gov website belongs to an official government

organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A

lock (

) or https:// means you've safely connected to

the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official,

secure websites.