NPS The Escalante Subdistrict has no marina or launch ramp access to Lake Powell. It does, however, provide for some of the best backcountry hiking and camping experiences within Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. Much of it is managed as part of Glen Canyon's proposed wilderness. The lower section of the Escalante River, approximately 12 miles, can be reached by boat from the main channel of Lake Powell. All of the canyons in the Escalante drainage feature excellent hiking opportunities. Trip PlanningServicesEscalante is a small town, typical of rural southern Utah, however most major tourist services are available, including: motels, a Bed & Breakfast, RV Parks, gas stations (including towing service and auto mechanic), restaurants, grocery stores, a farm supply center, art galleries and gift shops. There is a medical clinic that is open Monday through Friday. The nearest hospital is in Panguitch, about 70 miles west of Escalante. The Escalante Interagency Office is located on the west side of town. This houses a visitor information center, as well as the combined offices for the Dixie National Forest, the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, and the Escalante Subdistrict of Glen Canyon National Recreation Area. There are also numerous Forest Service, BLM, and State Park campgrounds in the area. Note that fires are not permitted in any drainages of the Escalante River and all of its tributaries. This is the same for the Grand Staircase-Escal

Coyote Gulch & Beyond

Make sure you are prepared for your hike to Coyote Gulch. Get your maps and permits, pack your gear, and see this beautiful area.

Floating the Escalante River

Or pushing, pulling, towing, and portaging your boat down the Escalante River

Driving Hole-In-The-Rock Road

Follow the wagon-prints of the 250 pioneers who crossed the Colorado and made a new settlement on the other side.

Image Gallery

Image Gallery

Image Gallery

Image Gallery

HistoryThe Escalante River was named in 1872 by A.H. Thompson, a member of the Powell Survey who passed through the upper basin area on a mapping expedition. He was travelling through the area again in 1875 when a group of pioneers from the Church of Jesus Christ of latter-Day Saints were planning a settlement in the area. Thompson suggested they name their new town Escalante. The name comes from the Dominguez-Escalante Expedition of 1776. Two Spanish priests, friars Dominguez and Escalante, traversed much of the southwest in a grueling expedition in an attempt to reach California from Santa Fe, New Mexico. The party did not reach the Escalante drainage, but Thompson, who knew the history of the area, thought it would be a good way in which to honor one of the first known explorers of the Southwest. Ranching was one of the primary occupations of the new village and the cowboys soon began to push their way into the many canyons of the Escalante seeking good grass and lost cattle. They were among the first non-native people to see the arches, bridges, alcoves, and other wonders which draw visitors today. Just prior to World War II, a proposal was put forth in Congress to create Escalante National Park. This proposed park included not only the canyons of the Escalante, but most of southeastern Utah. World War II intervened however and the proposal was all but forgotten in the crush of legislation related to fighting the war. Afterwards, some felt that national priorities had changed and Congress was, perhaps, more reluctant to restrict extractive activities such as mining on so large a chunk of land. Eventually, several national parks and monuments were created in this area, though even their combined size did not approach that of the original Escalante National Park - the park that almost was.

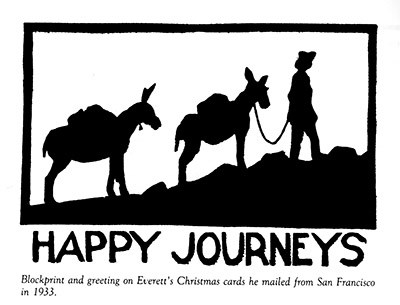

Everett Ruess"…[T]here is always an undercurrent of restlessness and wild longing, 'the wind is in my hair, there's a fire in my heels,' and I shall always be a rover, I know." Everett Ruess In 1934, an aspiring artist and adventurer, 20 year-old Everett Ruess, arrived in Escalante to continue pursuing his vision of wandering wild areas, including the vast canyon country of the Colorado Plateau. After spending time in Escalante getting to know local residents, he struck out with his burros in the direction of the Escalante canyons. He was never seen again and the mystery that resulted endures as one of the greatest known in the region. At first, his parents, accustomed to not hearing from Everett for long periods, waited for word from him. Some four months later, however, they began sending letters to various people in the region seeking assistance in finding their son. Over the next year, four different searches were conducted, one of which enlisted the assistance of an expert Navajo tracker. During one of the searches, they found his burros, nearly starved but alive, in Davis Gulch. Also found was an inscription: "Nemo 1934." What "Nemo" meant remains open to speculation, but his parent thought that it might mean "no one," perhaps reflecting on Everett's desire to be a part of the unknown wilderness. Several theories exist to explain Everett's disappearance. Some speculate that he continued his wanderings with a backpack and departed the region altogether. Some suggested that he might have climbed up crumbling cliffs to explore ancient ruins and fell to his death, the body covered by blowing sand. Others suggest that he may been murdered by cattle rustlers. It had been rumored at the time of Everett's disappearance that the government was sending an agent to the area to investigate a series of livestock thefts. It was speculated that Everett might have been mistaken as such an agent. The Navajo tracker, however, claimed that Everett had entered Davis Gulch, but had not come out; he stated there were no other tracks except Everett's. For more information about Everett Ruess and his wanderings, read Everett Ruess: A Vagabond for Beauty, by W. L. Rusho, Peregrine Smith Books, Salt Lake City. |

Last updated: September 20, 2024