Park managers, who were stationed at Mount McKinley National Park and then Sitka National Monument, initially planned to construct a hotel in Sandy Cove. With the onset of World War II, however, the military developed Gustavus Point Airfield, and park officials modified their plans. Recognizing that there were no hotels for travelers with delayed flights due to inclement weather, park managers planned to construct a lodge closer to the airport, at Bartlett Cove, with the potential to accommodate both park visitors and delayed travelers.

Mission 66 would be responsible for the construction of new park administrative facilities, roads, campgrounds, amphitheaters; At this time, the NPS turned away from the expensive log-based, rustic style architecture that dominated national parks in the early twentieth century, and moved towards modern architecture and building techniques. The NPS would adopt their own architectural style that blended rustic with modern, which would become known as “Park Service Modern.”

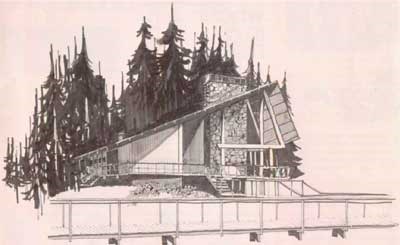

In 1964, the NPS hired the Seattle-based architect, John Morse, to design the lodge at Bartlett Cove. Morse had just completed the visitor center at Sitka National Monument. Primarily working in Washington State, Morse was known for his work in the modern “Northwest Regional” architecture, a regional variant of the more widely known “International Style.” With a strong background in modern architecture, Morse designed a Park Service Modern style complex that employs heavy timber posts, indicative of the rustic style with an overall modern design in cedar characterized by its enormous, asymmetrically pitched roof, offset triple triangular dormers, and expansive windows. The distinctive roofline is now mirrored throughout the park. The central lodge, with a check-in area and dining room, is flanked by wings of cabins with features that echo the design of the lodge. The complex is connect with a system of boardwalks through the forest.

Glacier Bay Lodge was a jewel in the Mission 66 crown, reflecting the cultural and scenic heritage of Glacier Bay through modern architecture. In the main lodge, the exposed carved wooden beams evoked traditional Tlingit clan houses. Before the second story was added, light filtered through the tall windows like light through the trees in the forest. Uncovered walkways immersed guests in the rainforest as they walked to their cabins. Chapters of the American Institute of Architects bestowed several awards on the Lodge.

Today, the Glacier Bay Lodge, like all Mission 66 projects, serves as an enduring reminder of the efforts of the National Park Service to welcome, accommodate, and serve generations of visitors. Over the next few years, Glacier Bay is embarking on an ambitious series of projects to renovate the lodge. This summer guests will enjoy new furniture in rooms and the lobby, renovated boardwalks, and even a new boiler system. Park staff will continue to be busy with a variety of interior and exterior improvements, ensuring another 50 years of welcoming visitors to their National Park.

|

Last updated: November 13, 2025