Commanding OfficersBy the time Captain Simon Snyder took command of Fort Larned in April 1873 the era of the railroads on the prairies was well underway. In 1872 Major General William Sherman expressed the opinion that the railroads, which had by this time replaced the Santa Fe Trail as a commercial highway, were important assets for the military to protect. Not only did they help the Army rapidly transport troops and supplies to wherever they were needed but they also did so with less expense than previous modes of transportation.

|

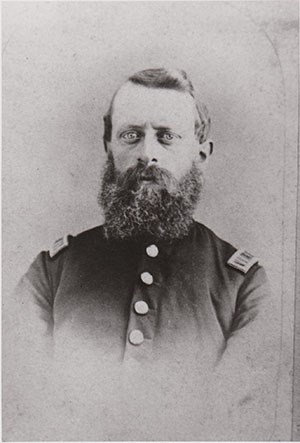

Public Domain Sherman also believed that what was commonly called the “Indian problem”, i.e. removing Indians from the Plains in order to make room for White settlers, lessoned in direct proportion to the growth of the railroads. Eventually the railroads would bring enough settlers to the plains that the southern and northern Indians tribes would be permanently separated, thus eliminating the problem. Certainly Capt. Snyder didn't have to deal with any dire situations with Indians. During the first four months of 1873, there was no mention in the post returns of Indian movements in the area. People still used the Santa Fe Trail to get to Colorado and other points west, however, nobody at the post kept a log of the wagons or “armed men” passing by. Also, according to the records, the post commander didn't feel there was enough of a threat from Indians to justify sending out patrols along the Santa Fe Trail, or to scout the area around the fort for signs of war parties. Events at Fort Larned, as they had been for several years now, were fairly quiet and routine. Soldiers planted gardens in April and two companies from the 6th Cavalry passed the fort on their way to Camp Supply in Indian Country. Company D, 5th Infantry transferred to Fort Dodge, leaving only 56 enlisted men under Capt. Snyder’s command. Settlement in the surrounding area continued at a fast pace with people moving to Larned and the nearby community of Camp Criley (later Garfield). This small settlement located near Coon Creek had been a favorite Indian ambush site in earlier years. Now it was a growing farming community. Simon Snyder entered the Army in Pennsylvania as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 5th U.S. Infantry on April 26, 1861. He was promoted to 1st Lieutenant on June 25, 1861, and then to Captain on July 1, 1863. He came to Fort Larned in May of 1872 as Captain of Co. F of the 5th U.S. Infantry. June 22, 1874. Capt. Snyder’s daughter, May Lillian Snyder, was born on January 24, 1872. His wife died within two years of their daughter’s birth, leaving Captain Snyder as a single parent. It was hard enough for Army officers to keep their children with them when their wives were there to help out, but it was even more difficult for a single father in the Army to raise a child. Capt. Snyder kept Lillie with him and managed to raise her on his own, but it was not easy when he had to be away on campaign for extended periods of time. In June of 1874 Co. F, 5th Infantry was ordered to Fort Leavenworth while Co. E of the 5th was sent to Fort Riley. These companies were replaced by Companies A and B of the 19th Infantry, which came west after duty along the Gulf Coast. Capt. Snyder went with Co. F to Fort Leavenworth and was replaced by Captain J. W. Lyster from the 19th. Simon Snyder went on to become a Major in the 11th Infantry on March 10, 1883, and was then promoted to Lt. Col of the 10th Infantry on Jan 2, 1888, and then became Colonel of the 19th Infantry on September 16, 1892. He was honorably discharged from volunteer service on May 12, 1899 while also receiving a promotion to Brigadier General of Volunteers. He was promoted to Brigadier General in the Regular Army on April 16, 1902, and retired on May 10, 1902. Despite the difficulties of raising a motherless child on frontier Army posts, Capt. Snyder succeeded in keeping his daughter with him at all his postings throughout the west. He also managed to provide her with special celebrations for her birthdays and holidays. When Lillie turned 15 her father reluctantly sent her to the Convent Mount de Chantal in West Virginia for further education. By 1874 had changed quite a lot at Fort Larned, mainly due to the railroad. In 1864 a board of survey at Fort Larned might have asked a subsistence officer why a sack of flour was lumpy while 10 years later records show them discussing what to do with a wagonload of fresh cabbages brought by rail to Larned. Even the cattle coming to Fort Larned for fresh beef were actually fat enough to slaughter and eat. The main change for the soldiers at Larned, though, was that the days of escorting wagons was definitely over, and a period of inactivity and boredom was setting in. Until the Army finally closed the post there was not much for the soldiers at Fort Larned to do besides keep up the daily routine of the garrison.

|

Last updated: February 20, 2024