Jean Seavey, NPS volunteer Approximately 86 percent of Everglades National Park has been designated the Marjory Stoneman Douglas Wilderness. As the largest wilderness east of the Rocky Mountains and the only subtropical wilderness in the United States, this wilderness offers a unique opportunity to study, document, and preserve lichens. Lichens exist in every terrestrial habitat within Everglades National Park and on all substrates, such as tree bark, rock, leaves, and soil. Although Everglades National Park is known for its extensive sawgrass marshes, lichen diversity is richest where trees are present. Tree islands and cypress domes visible from the main park road provide excellent habitat for native lichens. Other forested communities such as tropical hardwood hammocks and mangroves also support a large lichen flora. Casual viewers typically see lichens as a constituent of tree bark. Lichens even grow on manmade substrates, such as on asphalt and concrete in parking lots, along roadsides, and in developed areas. Close inspection reveals a special lichen world unique to subtropical Florida.

Jean Seavey, NPS volunteer What Lichens Are Lichens cannot be classified as a single entity like plants because they are a composite of fungi (lichen’s mycobiont) and green algae or blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) (lichen’s photobiont). Alga are capable of producing food by photosynthesis but fungi cannot produce their own food. In this special biological relationship the fungus provides a protective exterior surface for the alga. This enables the alga to exist in full sun thus maximizing its ability to produce food for both. This mutually beneficial relationship is called symbiosis, although many now consider it a controlled parasitism of the photobiont by the fungus. Lichens carry the name of the fungal lichen partner.

Jean Seavey, NPS volunteer What Lichens Look Like A bewildering variety of color and form are found in the lichens of Everglades National Park. Lichens can look like little shrubs, drape tree limbs like Spanish moss, or appear as little dots, lines, or smudges. Their color range is wide and includes red, yellow, green, gray, and white. Many are very small but others can cover large areas. For taxonomic purposes they are divided into four growth forms: crustose (crust-like), foliose (leafy), fruticose (shrubby), and squamulose (scale-like). Crustose lichens are the most common form present in Everglades National Park and in other subtropical and tropical regions of the world. They are distinguished by their tight adherence to substrate, which makes it impossible to remove them without including part of the substrate. Taxonomically they are divided into numerous groups on the basis of fruiting body shape and internal structure.

Jean Seavey, NPS volunteer Identification of crustose lichens involves viewing the external and internal structure of lichen fruiting bodies through microscopes. External features can be viewed with a low-magnification inspection scope, and internal structures such as spores and asci (sac-like cells containing ascospores) can be viewed with a higher-magnification compound scope. Identification also involves testing the chemical composition of lichens with Thin Layer Chromotography. These methods are time consuming but simple in comparison with interpretation of the results. Reference material is scattered worldwide, often difficult to obtain, and expensive or not available at all. Foliose lichens are leafy in appearance and loosely attached to the substrate. The top side is easily distinguishable from the bottom side. They can be flat, leafy, or convoluted, and can contain multiple ridges and bumps.

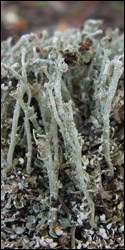

Jean Seavey, NPS volunteer Fruticose lichens are typically the most glamorous and showy. The word "fruticose" is a technical term meaning "shrubby" and has nothing to do with fruit. This shrub-like growth form is the most highly developed and plant-like of the four forms, and some species of fruticose lichen can be difficult to tell apart from plants. Fruticose lichens often appear to be miniature shrubs. They are often densely branched and the most three-dimensional, often with a single point of attachment to the substrate. The growth rate of lichens is variable and depends on multiple factors, including the species of lichen. Substrate is also important; a lichen growing on organic tree bark teeming with nutrients will grow at a different rate than a lichen growing on an inorganic solid rock. Growing conditions, such as climate and amount of sunlight, also affect the growth rate.

Jean Seavey, NPS volunteer Squamulose lichens have scale-like lobes called squamules that are typically small and overlap to form mats. The squamules are attached to their substrate at one end, like a tiny shingle. Squamulose lichens are similar to crustose lichens at the base, with leaf-like squamules that are lifted up off of the substrate. The growth form of squamulose lichens is intermediate between that of crustose and foliose lichens. Because of the similarities in small size and stature, crustose and squamulose lichens are generally grouped together as microlichens. The larger foliose and fruticose lichens are generally grouped together as macrolichens. Some species of lichen are combinations of the fruticose and squamulose growth forms. The "fruticose" stalks of Cladonia cinerella (see photo at left) develop from a "squamulose" base. Although many species of crustose lichens are conspicuously lobed at their margins and appear to be foliose, they are classified as crustose because they are in intimate contact with their substrate over most of their lower surface. Similarly, some species of foliose lichens are so tightly attached to their substrate that a microscope is needed to check to make sure that the lichen is indeed foliose. How Subtropical Florida Lichens Compare with Lichens from Other Places

Jean Seavey, NPS volunteer Until recently it was believed that lichen abundance and species richness were greatest in cool-temperate areas. Now, about half of the predicted global 26,000 –28,000 lichen species are estimated to occur in the tropics (Dr. Robert Lücking, The Field Museum of Chicago, 2009), which represent less than 25 percent of the Earth's land surface. Most areas of the continental United States have been well studied except the tropical and subtropical parts. Available publications document the extraordinary diversity, especially of crustose epiphytic microlichens, and suggest that many species await discovery and could provide substantial additions to the North American Lichen Checklist. At a lichen workshop at Fakahatchee Strand Preserve State Park in southwestern Florida in March 2009, 369 species of lichen were identified, 7 of which were new to science and 45 new to North America. Subsequent research efforts ranked Everglades National Park fifth in lichen diversity in a comparative analysis of protected areas within the United States.

Jean Seavey, NPS volunteer Everglades National Park Lichen Project As of 2014, the Everglades National Park lichen project has identified 550 species of which at least 50 are additions to the North American Lichen Checklist. Thirteen species have been described and published as new to science and an additional 7 new species are in press. At least 10 others are believed to be new to science but have not been described. More than 3,000 specimens have been delivered to the National Park Service South Florida Collections Management Center for archiving, and several hundred more are currently being processed. Lichens are good barometers of air and habitat quality. After sufficient baseline data on Everglades lichens have been collected, it is hoped that analysis of those data may provide insight to their potential use as environmental indicators. Learn more about Rick and Jean Seavey, the volunteers who are conducting the Everglades National Park Lichen Project, below. Volunteer Profile: Rick and Jean Seavey Rick and Jean Seavey have been research collaborators with Everglades National Park for more than 25 years. Honors include the Marjorie Stoneman Douglas Award from the Dade Chapter of the Florida Native Plant Society in 1989 for first use of large community volunteer groups in non-native plant removal (Royal Palm Hammock), the George B. Hartzog Award from the National Park Service (2009) Enduring Service Category, and the naming of a lichen (Heiomasia seaveyorum Nelson & Lücking) in their honor in 2010. Rick Seavey is the only known systemic taxonomic lichenologist in south Florida and possibly all of Florida. Visit the Seavey Field Guide website and learn more about subtropical Florida lichens. Rick and Jean lead the Everglades National Park lichen project, which is being conducted completely by volunteers. Major contributions have been made by seasonal, local, and student volunteers. Support has been provided by the National Park Service volunteer program, Everglades National Park Inventory and Monitoring Program and Science Communication Team, and the South Florida National Parks Trust. The Seaveys are always looking for help! Call the Everglades National Park Volunteer Coordinator at 305-242-7752 to learn how you can volunteer to help Rick and Jean with their lichen project or with any of the many other opportunities available in the park. Current Volunteer Opportunities |

Last updated: July 28, 2015