Evolving Research on Ethnographic Resources: Resources—Places—Landscapes

Rebecca S. Toupal, Bureau of Applied Anthropological Research, University

of Arizona

February 26, 2003

Abstract: Ethnographers with the Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology's (BARA) Native American Cultural Resource Revitalization (NACRR) Program have over twenty years of field experience with Native American ethnographic resources. During that time, they have found the need to broaden their investigations from resource-specific studies to holistic place studies and finally to landscape research. Much of the motivation for these changes derived from the need for information beyond basic resource identification, general uses, and management impacts. Questions of context and connections prompted exploration of the meaning of resources and places. Additionally, changing needs of and requirements by contracting agencies influenced the ways in which BARA ethnographers organized their research and reporting methods. The review of several projects demonstrates the growth of BARA's ethnographic resource research. The approach to resource-specific ethnographic investigation is illustrated with a power line impact study conducted in Utah in the early 1980s. The change to a holistic approach to place and resources occurred in the mid-1990s with studies at Zion National Park, Utah and Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona. BARA's landscape approach began to take shape in 1997 during a rock art assessment project on the Nevada Test Site. The first NPS project in which it was applied was with traditional Ojibwa resources in four western Great Lakes parks. The landscape approach to the Ojibwa project generated a complex of ethnographic resource data that prompted the use of an ACCESS database to organize and manage the information. With this software, electronic forms matching those used in the field were developed for data entry, and responses queried by specific parameters such as gender, park, and resource to aid report write-up. While the ACCESS database continues to be used with raw data, further development of it was interrupted with the introduction of NPS's Ethnographic Resource Inventory (ERI). The four categories of the ERI—natural resources, objects, places, and landscapes—reiterate our experience with increasingly complex ethnographic resources. The development of a partial to complete record for a natural resource or object, for example, is more readily achieved than that for a place or landscape. Questions of context, connections, and meaning that prompted us to take a landscape approach to ethnographic resources also arise when developing a place or landscape record in the ERI. Fields and records, however, are not cross-referenced with other fields or records, nor is there a field to address connections. Functionality of this nature along with more querying options could be useful for management and reporting purposes as well as allowing resource comparisons to be made based on ethnic group, park, or some other parameter. While the ERI provides a way to systematically code and report ethnographic resource data, we have found it to be an addition to rather than substitute for consultation, data entry, and reporting. We enter data by summarizing interview responses from the BARA database and placing the summaries in the appropriate ERI fields. Also, while we can print reports from the ERI, we have encountered problems of missing resources, duplicated resources, and missing data. We have also found the format to be inadequate for our written reports, and for review by consultants who often want to know how the knowledge they shared is used. Without a report or document that shows this, they may be reluctant to share more knowledge or participate in other management matters. Other issues that impede data collection include problems that arise from cultural rules for sharing knowledge, knowledge lost between generations, and projects perceived by affiliated and associated groups as inappropriate. The limitations of the first two issues can be mediated with in-depth literature, document, and archival reviews. We have encountered the latter issue, however, as a result of inadequate consultation and communication between parks and traditional groups. Two projects, Isle Royale and Pipestone, provide illustration of this challenge to ethnographic research.

Ethnographers with the Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology's (BARA) Native American Cultural Resource Revitalization (NACRR) Program have over twenty years of field experience researching Native American ethnographic resources. During that time, we have found the need to broaden our investigations from resource-specific studies to holistic place studies and more recently to cultural landscapes.

Much of the motivation for the changes to our research strategy derived from the need for information beyond basic resource identification, general uses, and tangible management impacts. Questions of context and connections prompted exploration of the meaning of resources and places, spatial and temporal extents, and the influence of cultural variables. Additionally, changing needs of and requirements by contracting agencies influenced the ways in which we organized our research and reporting methods. In this chapter, I discuss several projects that illustrate the changes in our research strategy, our shift to electronic data management with in-house and agency databases, and challenges that we have encountered to data collection.

Changing Research Methods

Four projects illustrate the development of our ethnographic resource research: Puaxant tuvip "Sacred Land", Zion National Park and Pipe Spring National Monument, Storied Rocks, and Ojibwa Traditional Use in the Great Lakes area. Our approach to resource-specific ethnographic investigation began with a power line impact study conducted in Utah in the early 1980s. We took a holistic approach to places and resources in the mid-1990s with studies at Zion National Park, Utah and Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona. Our landscape approach came out of the Zion work in 1998 with an ethnoarchaeology project on the Nevada Test Site. We expanded it in 2000 with a landscape form for an NPS project involving traditional Ojibwa resources in four western Great Lakes parks.

Puaxant tuvip "Sacred Land"

The Intermountain Power Agency (IPA) planned to construct a power-generating system from Utah southwest into southern California in the 1980s. Over 1,000 miles of transmission lines would be run across lands used traditionally by the Goshute, Pahvant Ute, and Southern Paiute peoples. The BARA ethnographers investigated cultural resources that potentially would be adversely affected by the construction and presence of the transmission lines. In doing so, they asked the Native American participants about cultural items and cultural places independent of other cultural resources. Specifically, they wanted to know how concerned Indian people were about potential impacts, how Indian people felt about having more power lines constructed, what mitigation actions should be taken for affected items, places, and burial, and whether Indian people believed the information they shared would be considered.

The results of the study included several recurrent points in the discussions of specific items or places. Sections of the power lines were identified as crossing parts of the Indian people's traditional Holy Lands suggesting a broader area of impact beyond the power line footprint. The participants expressed concern about impacts to everything within their Holy Lands including minerals, the soils from the surface to the center of the earth, water, and all living things. They repeatedly described interrelationships between cultural items within the Holy Lands thereby introducing processes as part of the array of cultural resources.

Zion National Park and Pipe Spring National Monument

In the mid-1990s, the National Park Service sought an ethnographic study of Southern Paiute cultural resources in Zion National Park, Utah and Pipe Spring National Monument, Arizona. Beyond identification and use information, NPS wanted to know how these resources were related to the natural ecosystems that surround and incorporate these administrative units. The Virgin River ecosystem in Zion and the Kanab Creek ecosystem in Pipe Spring provided the physical basis of the study.

The study was special in two ways: it moved beyond the formal boundaries of park units in an effort to understand them as components of a broader natural ecosystem, and it involved Indian tribes in the design and conduct of research to give them a voice in how their cultural resource issues would be studied and presented to the NPS. Since the power line study, we had contemplated how to address processes in our cultural resource studies and the Zion project provided an opportunity to do just that. We shifted our research strategy to a holistic place study that would accommodate the ecosystem approach desired by the Southern Paiute people and the NPS.

In order to achieve an integrated approach of functions, values, and relationships between resources, we used four scales of analysis: ecoregion, ecosystem, park, and place. While we attained an in-depth indigenous perspective, we also encountered issues concerning the sharing of knowledge. Knowledge is important, sacred, and critical to survival, so Indian people restrict what they share about something. If the person who receives the information treats in a culturally correct manner, then Indian people typically share more information.

Traditional knowledge also is unevenly distributed because some Indian people are specialists in plants, animals, places, or other resources, and some knowledge is highly privileged. When the federal agency funds resource-specific studies, tribal governments can send people who specialize in these topics. Often multiple resource-specific studies are necessary because the cultural significance of a natural resource can vary by location or season. Certain Southern Paiute medicine plants, for example, acquire more power because they are near the Colorado River in the Grand Canyon.

Southern Paiute interpretations of the two riverine ecosystems revealed a complexity of connections and relationships, and a landscape-scale of understanding resources including plants, animals, water, minerals, archaeology, rock art, and air. They spoke of general use patterns such as food, ceremonies, medicines, and crafts but also more specifically about some uses of food and craft resources. They shared their taxonomies for air and water, which they view as separate, living entities that exist in different forms. Throughout their discussions, connections and relationships among resources, places, and people recurred, illustrating the cultural roles associated with ecosystem processes.

Storied Rocks: American Indian Inventory and Interpretation of Rock Art on the Nevada Test Site

This study was conducted as part of a government-to-government consultation between the Department of Energy/Nevada Operations Office (DOE/NV) and the American Indian tribes and Indian organizations that make up the Consolidated Group of Tribes and Organizations (CGTO). The study focused on 10 rock art sites, seven of which were on the Nevada Test Site (NTS), and three of which were in the Yucca Mountain Project (YMP) area. We conducted a systematic ethnographic study of petroglyphs, pictographs, and other rock manipulations, generally referred to as "rock art," to develop a better understanding of the cultural significance of rock art for contemporary American Indians and its place in their traditional cultural landscapes.

Methodological changes included distinguishing between individuals, their families, and their ethnic groups in terms of relationships with and use of rock art sites, transmission of knowledge about the sites, and meaning of the rock art and/or sites. Connections to other resources and places, including other rock art sites, seasonality and timing of use, and condition and impact assessments further clarified cultural landscape processes for resource managers.

The overall finding of this study is that the rock art sites in the study areas constitute processes of a living landscape. The place of rock art is one of differential use, that is, behaviors and activities conducted at rock art sites may be quite different than at other places in the landscape. In Nevada, rock art types include rock rings or other surface alignments, petroglyphs, pictographs, cupules (cup-shaped depressions), and geoglyphs (figure or symbol cut into the earth). In terms of relationships with other resources, rock art sites typically have water, food plants, medicine plants, animals, paint sources, minerals, and basket-making materials. Dark volcanic rock, vertical rock or cliff faces, and large rock surfaces are not uncommon although not all such sites will have rock art.

Rock art as a permanent modification of the natural landscape is not unlike a form of architecture that reflects a delimiting of social, political, and religious spaces. Rock art sites are differential as well depending upon their location and the type of markings or modifications. These sites may be gender-specific or for individuals, teaching, or groups. Individual or teaching sites, for example, tend to be in areas of limited access that afford much privacy.

Implicit in all rock art sites are connotations of ritualism and ceremonialism. Most telling of landscape processes associated with rock art sites are the stories, songs, and song trails that connect the sites with other places, resources, and the people of the cultural landscape.

Traditional Ojibwa Resources in the Western Great Lakes

In this ethnographic study, we collected data about natural and cultural resources of contemporary significance to Ojibwa people in four NPS units: Sleeping Bear Dunes National Lakeshore, Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore, Apostle Islands National Lakeshore, and Voyageurs National Park. The objectives were to provide an overview and assessment of Ojibwa land and resource use in and around the parks, and to develop an inventory of ethnographic resources as an information database to aid decision-making.

We developed an ACCESS database to manage the data collection of this project, which occurred before the NPS's Ethnographic Resource Inventory, also ACCESS-based, was developed. Basing it on the history and ethnography of land and resource use, we organized it by 11 activity complexes including links among resources and various activities such as ricing and fishing. Our database accommodated multiple uses of single resources, connections among resources, between resources and people, and between people and the land, and different types of connections including physical, behavioral, and spiritual.

The findings included identification of 488 plants, wild and cultivated varieties, and 79 animals; each resource could be cross-listed by park, habitat-type, type of resource, and site, and could accommodate other resources including minerals and landscape features. Water resources at all four parks had great cultural significance, and details about water uses revealed a complex connectivity throughout the region and among the Ojibwa bands.

Our database allowed us to address more effectively the broad extent of the Ojibwa people's relationship with and use of the aquatic ecosystem. The trend of increasing complexity and need to understand cultural relationships with the land at a landscape-scale continues with each project. Electronic databases allow us to capture and analyze cultural data more thoroughly and quickly, consequently, benefiting the cultural groups and resource managers associated with the projects.

Electronic management of data

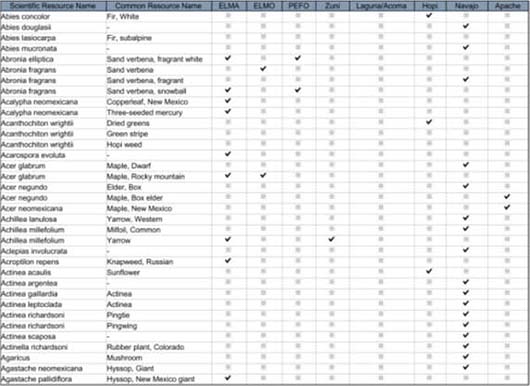

Our first use of an ACCESS database was with an NPS project involving three southwestern Parks. In this initial effort, we identified plants and animals associated with each park and ethnic group. The resulting tables allowed us to run queries based on these parameters to create lists of species common to groups and/or parks (Figure Toupal-1).

Figure Toupal-1 ACCESS database query output of plants associated with three southwest parks and one to five ethnic groups.

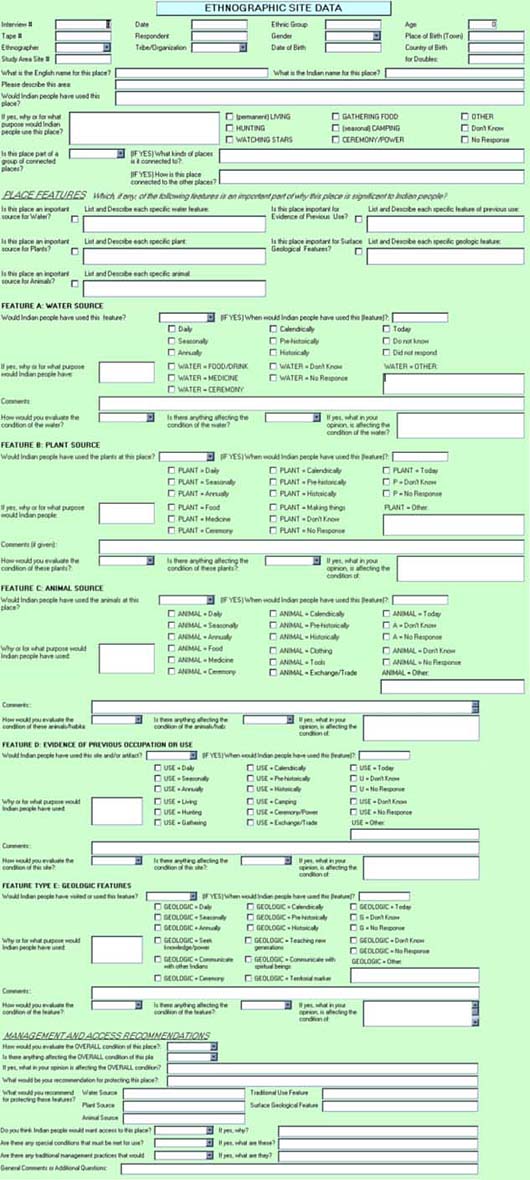

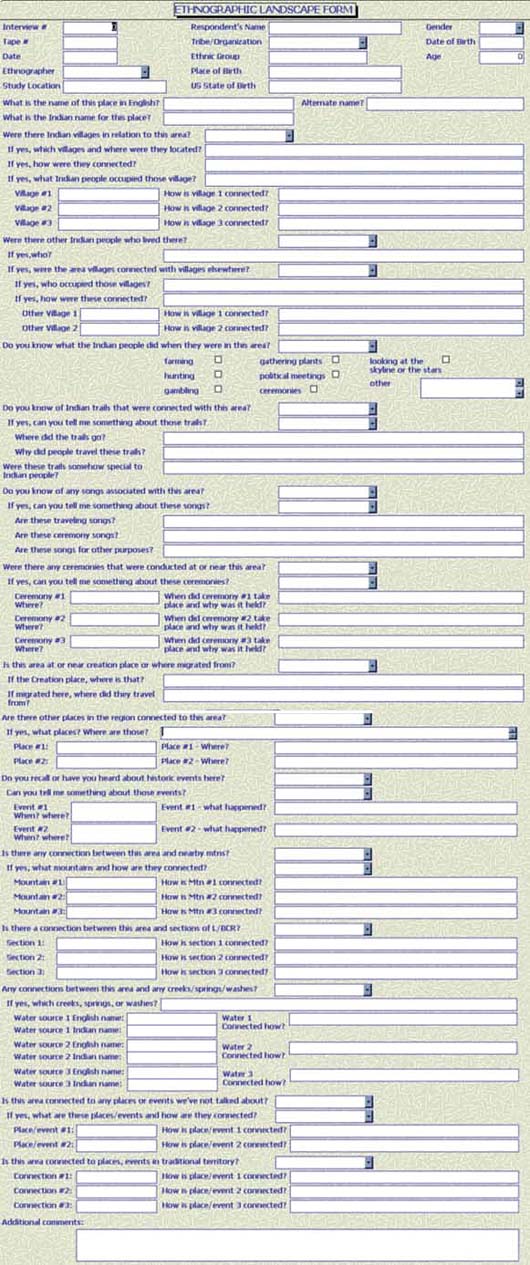

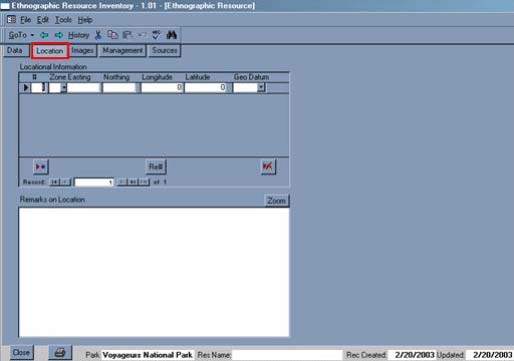

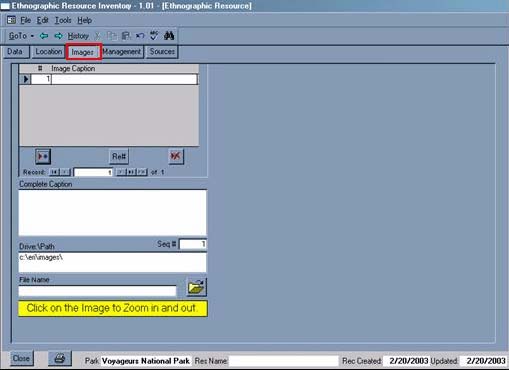

The landscape approach to the Ojibwa project generated a complex of ethnographic resource data that prompted more advanced use of an ACCESS database to organize and manage the information. With this software, electronic forms that replicated those used in the field were developed for data entry, and responses were queried by specific parameters such as gender, park, and resource to aid report write-up (Figures Toupal-2 and Toupal-3). While we continue to use ACCESS to manage our raw data, further development of it was interrupted with the introduction of NPS's Ethnographic Resource Inventory (ERI).

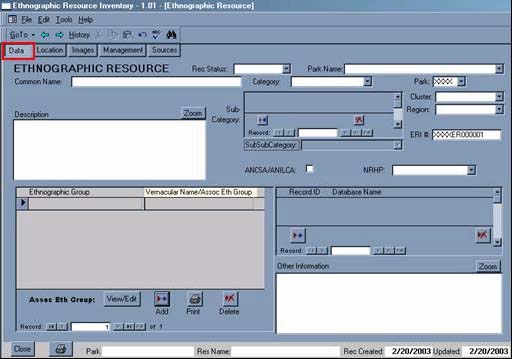

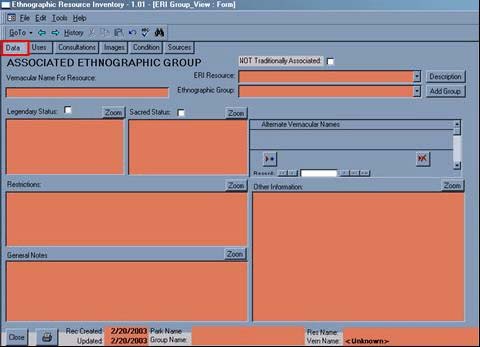

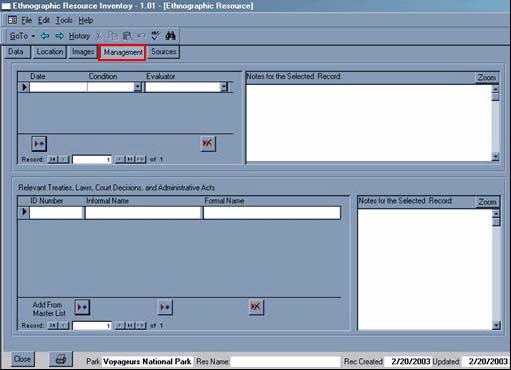

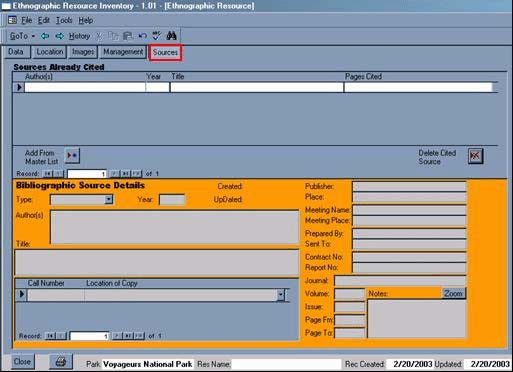

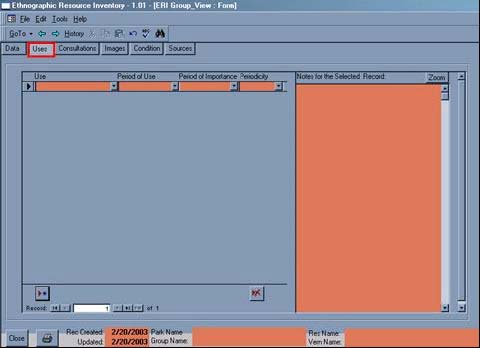

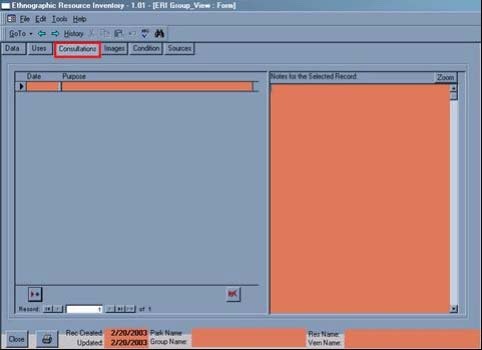

The four categories of the ERI—natural resources, objects, places, and landscapes—reiterate our experience with increasingly complex ethnographic resources. The program serves a different purpose than our databases. It is designed for park management rather than comparisons and analysis of data, and is much more detailed and complex than our databases. It also distinguishes between Ethnographic Resources (Figures Toupal-4a-e) and Ethnographic Groups (Figures Toupal-5a-f).

Figure Toupal-4b. ERI's Ethnographic Resource Location window.

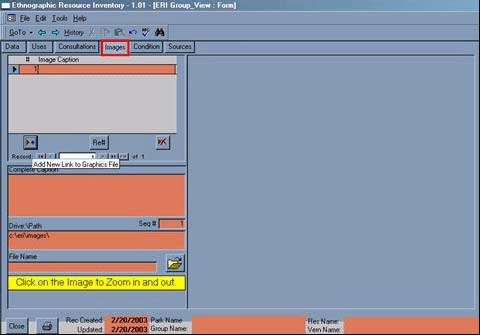

Figure Toupal-4c. ERI's Ethnographic Resource Images window.

Figure Toupal-4d. ERI's Ethnographic Resource Management window.

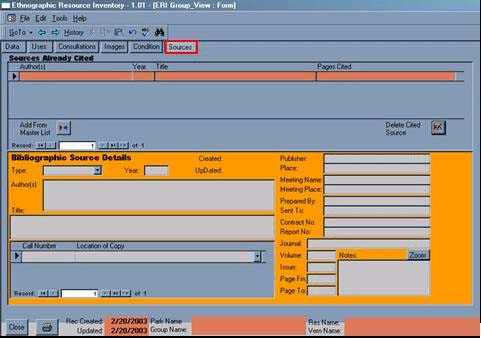

Figure Toupal-4e. ERI's Ethnographic Resource Sources window.

Figure Toupal-5b. ERI's Ethnographic Group Uses window.

Figure Toupal-5c. ERI's Ethnographic Group Consultations window.

Figure Toupal-5d. ERI's Ethnographic Group Images window.

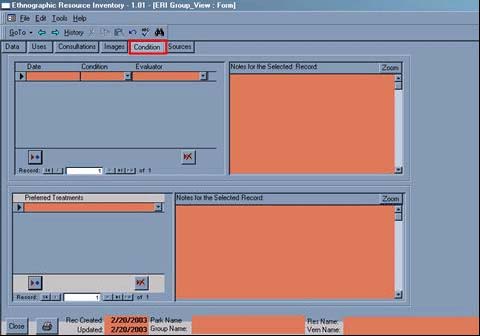

Figure Toupal-5e. ERI's Ethnographic Group Condition window.

Figure Toupal-5f. ERI's Ethnographic Group Sources window.

We have found the development of a partial to complete ERI record for a natural resource or object to be achieved more readily than that for a place or landscape. As we develop a place or landscape record, questions of context, connections, and meaning arise. Fields and records cannot be cross-referenced with other fields or records, nor is there a way to indicate that connections exist. These may not be issues for the parks, however, they do complicate inclusion of connection and relationship data, and analysis.

While the ERI provides a way to systematically code and report ethnographic resource data, its intent for park use makes it an addition to rather than substitute for our ethnographic research. We summarize interview responses from our databases and place the summaries in the most appropriate ERI fields. While we can print reports from the ERI, we have encountered problems of missing resources, duplicated resources, and missing data. We have also found the format to be an inadequate substitute for our written reports, and for review by consultants who often want to know how the knowledge they shared is used. Without a report or document that shows this, they may be reluctant to share more knowledge or participate in other management matters.

Two projects are underway that we anticipate will improve electronic management of ethnographic data. A web-based version of the ERI is being developed by NPS and will expedite data entry and access. An ethnographic project in a Midwest Region park includes the development of data collection instruments specific to the ERI that also will expedite data entry.

Challenges to data collection

The usefulness of electronic databases is limited by the kind and amount of ethnographic data that is collected. In addition to the need to show consultants how knowledge they share is used so that they will continue to share knowledge, there are other issues that complicate or impede data collection. Cultural rules for sharing knowledge, knowledge lost between generations, and projects perceived by affiliated and associated groups as inappropriate can greatly restrict access to the information sought by ethnographers. The limitations of the first two issues can be mediated with in-depth literature, document, and archival reviews, however, the latter issue may occur when there has been inadequate consultation and communication between parks and traditional groups.

Cultural knowledge is important, sacred, and critical to survival. When cultural rules for sharing knowledge complicate data collection, it may be due to who is being asked, when they are being asked, and where they are being asked. Different people know about different aspects of a resource or its use. Cultural significance may vary by resource location, or by season; the telling of stories that reveal a resource's significance may be restricted to certain times of the year.

Three projects, Isle Royale National Park, Pipestone National Monument, and the Flagstaff area monuments provide illustrations of how inadequate consultation and communication can impede ethnographic research. These examples also illustrate the need for in-depth literature reviews as the foundation for ethnographic studies rather than as support or guide to field findings.

At Isle Royale, a non-Indian ethnographic study, consultants wanted to know why they should talk about their places when the park had a history of burning and bulldozing homes when the residing families were absent. Although they shared cultural data with us, the consultants felt the study was too late to do any real good.

We encountered one of our most challenging projects at Pipestone. Dakota consultants expressed much anger about the study being conducted before the cultural issues concerning the treatment of pipestone material were settled. They felt that plants were an inappropriate starting point, that they needed to talk about the pipestone first, but that communication and consultation between the park and tribes had been limited and ineffective. While we collected some ethnobotanical data, it was less than we anticipated and we had to use methods less structured than our normal routine.

The Flagstaff area monuments include Sunset Crater Volcano, Walnut Canyon, and Wupatki. Although the park staff had put much effort into developing good relationships with the area tribes, they and we were surprised when the Cultural Preservation Director for the Hopi Tribe reacted negatively to the study. He was upset because he thought the issue of cultural affiliation had been settled and to do a Traditional Use Study that would inform the parks for consultation purposes was to threaten the decision that had been reached. Although the park staff and we came to understand that he was distinguishing between culturally affiliated (NAGPRA), and traditionally associated (traditional use but not occupation, i.e. burial use of the area), we were unable to resolve the issue to his satisfaction and collected no data from the Hopi Tribe.

This account of the development of our research strategy reflects our efforts to be responsive to the needs of the cultural groups and agencies with whom we work. It reflects our application of lessons learned through our failures and successes, and through those of cultural groups and agencies. Where we go next depends on the next lessons learned.