Rural Ozark Women and Traditional Associations to the Ozark National Scenic

Riverway

Karen Gaul, Hendrix College and Corey Lashlee

February 27, 2005

Unidentified woman and boy in john boat, c. 1930s; OZAR Cultural Resources Office archives photo.

In addition to protecting natural resources, the National Park Service is charged with, in part, preserving historical and cultural resources, and engaging intelligently and respectfully with those people traditionally associated with park areas and resources (NPS Management Policy: 2001; NPS-28). Doing so means identifying who such associated peoples are, and conducting dedicated research focusing on ways their lives are related to parks and park resources. These rich ethnographic studies provide qualitative data that can better inform interpretation, management and protection. While many of the studies for the NPS ethnography program are standard Ethnographic Overview and Assessments, or studies focusing on the use impacts on certain resources, there are occasional Special Emphasis Ethnographic Studies conducted for the sake of filling out the ethnographic detail of a particular area.

One such research project, Women of the Riverways, focused on women's lives in and around the Ozark National Scenic Riverway in southern Missouri (Gaul and Lashlee 2001). The study examined the scope of women's work in and outside of the home, their roles in contributing to the family's livelihood, and their sometimes less visible roles in larger institutions such as church, school and politics over the last hundred and fifty years.

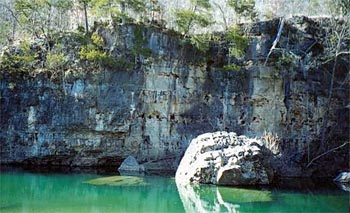

The Southern Missouri Ozarks

The Ozark hills are characterized by karst topography. Blue-green springs, caves, and clear riverways have long been features people have enjoyed and used. Fed primarily by the Ozarks' many springs, the regions' rivers in the past served as a means of transportation of people as well as timber and other materials. When flooded by heavy rains, however, they could become a hindrance to travel. Today, as in preceding decades, the rivers provide forms of recreation as well as various types of livelihood (Rhodes 1974; Beveridge 1990; Hall 1958).

Many of the residents in the Ozarks of southern Missouri have been tied to these hills for several generations. Some are of Native American descent (Zedeno and Basaldu 2002), but the majority is of Scotch-Irish heritage, perhaps from families who stayed in the Appalachians for some period before moving westward (Gerlach 1984; McNeil 1995). These people who have chosen to live along the riverways are to some degree shaped by the geographical and environmental surroundings in which they live. And they in turn alter their environments—to greater or lesser degrees—through such activities as hunting, agriculture, timber extraction, construction and road building. They have seen the area undergo radical environmental and cultural change, while maintaining important links to past traditions. Gender relations, and gendered interactions with local landscapes, are among the many cultural features that are changing with the times.

The earliest settlers found an area forested with hardwood white and black oak, as well as hickory, maple and black walnut. There was also an abundance of coniferous yellow short-leaf pine. For many years the Ozarks remained a lightly-touched semi-wilderness that provided first native peoples and later European settlers with everything they needed to fashion together a life. For the more permanent settlers, forests provided building materials for homes and furnishings, barns and fences. The Ozarks' chert-filled soil, somewhat more fertile along the lowlands and near rivers, was good enough to provide simple staples of corn, beans, potatoes, a variety of squashes and melons, peanuts and other vegetables. Some families grew non-food items such as tobacco and cotton, the latter of which could be made into clothes and bedding. Numerous grist mills along the river offered people a place not only to grind corn and wheat, but to gather and visit with other members of the community (Stevens 1991:32-35; Murphy 1982:88). In areas where the land was not ideal for farming, the Ozarks forested hills were rich with native species such as wild legumes and numerous grasses, which provided fodder for settlers' free-roaming livestock and fed the wild game of the area (Hall 1958; Murphy 1982).

A timber boom in the early 20th century radically reshaped the local environment. The river systems were used to float thousands of rafts of hardwood railway ties, and the pine was cut as well, until the forests were thoroughly cleared. Not only timber resources, but animal habitat, riverbeds and micro-climates were affected (Sauer 1920; Hall 1958; Murphy 1982; Stevens 1991). Elderly women, some of whom recall living in early timber camps, speak of changes they witnessed in the decades following the heavy deforestation of the area. It became harder to find animals to hunt. People looked for work in mining, transportation and other industries, which often took them out of the area of their homelands.

Tourism has become an increasingly important industry in the area, and the Ozark National Scenic Riverway draws thousands of visitors each summer. This influx of tourists is met with mixed responses from local residents. While many of them participate in and benefit from tourist-related businesses, they also rue the loss of quiet, and the easy access to the rivers that they enjoy during off-season.

The Ozark National Scenic Riverway

The Ozark National Scenic Riverway (OZAR) consists of stretches of land and waterways along the Jacks Fork and Current Rivers in southeastern Missouri. The Park was formed in 1964 when several State Parks along the Riverways were combined to make a National Park that stretches like a big reclining "Y" for some one hundred and thirty-four miles along the waterways.

Blue Spring, on the Current River; Karen Gaul photo, 2000.

The process of the setting up the Ozark National Park Riverway system was a rocky and controversial one. Most residents now agree that preservation by the NPS was the best outcome for their rivers. In order to protect contiguous stretches of land along the Riverway, the federal government purchased some private lands along the rivers, offering residents various options for continued residence or relocation. Families continue to use various parts of the park system in sometimes shared, and sometimes gender-specific ways. Additionally, a number of women and men are employed by the NPS, which offers opportunities for employment and a fair working environment that are not always easy to find in the region.

Women's Lives and Work

The women who have lived in and around the OZAR region have crafted family and community through a great deal of hard work. Technologies changed, various industries came and went, and the Ozark National Scenic Riverway was established. But even though women have seen a great deal of change in the last few generations, there are threads of continuity that stretch from homestead farming of the past, to state-of-the-art computerized classrooms of today.

Unidentified woman working with cows n.d..; OZAR Cultural Resources Office archives photo.

A diversified approach to family subsistence is a practice that has persisted for generations in these hills, with women and men pursuing multiple possibilities for food production and income. Most families lived in rural areas and, until recently, raised or traded for the majority of what they consumed. In the past as well as today, it was not uncommon for a person to have two or more paying jobs, and to perhaps sell garden produce, eggs or firewood, to offer child care, or to sell arts and crafts.

Researchers have noted the practice of multiple economic strategies as a hallmark of Ozarks culture (Stevens 1991; Gibson 2000). This is an environment that is not abundant in any one resource, but instead offers many small opportunities from which to piece together a living, and a diversified approach is a tried and true means of survival. When we consider the range of diversity in women's activities, we see that their gender, rather than limiting or confining them to certain kinds of work, meant that an even greater range work was delegated to them.

The division of labor between women and men was not always so neatly defined. Some women plowed, planted, and helped in the fields during the harvests of corn and other grains. They also chopped or sawed wood and split rails for fences. Of course, women would undertake such "man's work" for a variety of reasons…" (Stevens 1991: 128).

Most centrally, of course, women undertook "women's work." At the center of life was the family. Families have always been central to community building, and women were and are often at the core of family organization. Women typically have been primarily responsible for child care, socialization, and instilling moral values in children. They usually provide meals for the family, as well as clothing and other basic daily necessities.

In addition, simply running a farm meant many kinds of work. Most women remembered growing up on farms where quite a number of different tasks were necessary in a day or a season to pull together the family's subsistence, and this was often combined with paid work. Additionally, these multiple tasks often meant undertaking and supervising many different kinds of work simultaneously. One woman told of her mother setting up the children with a reading lesson for the morning while she went out to milk cows and do other chores. She would return to the house and redirect the children in additional activities as well. Women of the Ozarks may certainly have been some of the earliest and most successful "multi-taskers."

For most of us, it is probably difficult to imagine, just a few generations ago, how hard women worked and what such work entailed. Just to clothe one's family was often more complicated than simply making the clothes by hand. The fabric, if not purchased from a store, had to first be produced. Even after the cotton had been grown or sheep had been raised and shorn—and women were likely to have no small part in these endeavors—cotton or wool would then need to be picked clean, carded, and spun, woven and dyed. These were jobs that were almost exclusively women's. And such work would oftentimes take place at night when women's outdoor work was over for the day (McNeil, 1995: 37-42). Like making clothes, other kinds of work were also more involved than we might first imagine. Not so many decades ago, washing clothes or other items meant one had to first make soap, an extremely time consuming activity. Lighting for the home meant making candles. Quilts on the beds needed to be pieced together and stitched. Having food for the winter meant drying or later, when it was technologically feasible, canning the season's crops. Butter had to be churned and animals butchered, cleaned and prepared. A kitchen garden had to be tended, in addition to crops in the field. Cooking meant building a fire in the stove, and having enough wood on hand to do so. The list of work related activities for a life lived on a basis that was in most respects self-sufficient is a long one, and women were the sole participants in many of these activities and an important contributor in many others.

Women of this region are proud of what they consider to be a strong work ethic, and they remember with fondness the hard working days of the past. Of course, all of the work women did and do is supported and complemented by the work of men of the family, as well as others in the community. Women spoke about community cooperation on butchering day, barn-raising and corn husking, or big canning days. Men did focus on farm and field work that was primarily their responsibility. But women contributed to "men's" work in ways that was rarely true in the reverse.

Spatially, for example, we can see that women typically ran the household, with the kitchen at its center. Work also took them out into the yard for washing, butchering and care of chickens. The garden might be relatively near the house, and the sheds, barns and fields further out. Women went into forests to gather firewood, berries and greens, or to gather in grazing animals. And so they traversed spaces that expanded far beyond their kitchen door. Men, on the other hand, usually did not share a command of domestic activities that were typically understood as "women's." Women spoke about the range of domains within and across which they worked, demonstrating their ability to apply themselves as economic generalists in ways even more far-reaching than men, in many cases. One woman remembers some of the subsistence and income-generating activities her family would engage in as she was growing up…

We lived on a creek and they got a lot of creek bottom land…and [my father] raised watermelons and cantaloupes and peanuts and of course I had to help with the peepaw and I had to lay the vines…And they sold some garden products, eggs and chickens and stuff like that. Mom canned and she froze stuff…you know, put everything into…all kinds of jellies…[B]efore the kids started school she stayed home but…she…took care of a neighbor, an elderly woman, and they had milk cows…and she sold milk so she still worked all the time. Then after both kids were in school…she worked at restaurants in 1964 or 1965. I can't remember what year it was but it was in the 1960's she went to work in the nursing home here in Van Buren and that's where she worked until she retired.

Another woman remembers fondly,

I had a very special mother. She…married really young, but she was so intelligent and so widely read. And she was really clever. She could sew. And she was so industrious that we always had more to eat than any of our neighbors. In fact, on weekends, people would come in, and I can see now it was for my mother's cooking, you know.

Oh, she was the most marvelous cook and we always had good things to eat. And we all helped. By the time we were three or four we could wash fruit jars, you know. And my mother was always workin.' She canned all summer and then she would sew all winter and…we just had kerosene lighting. And my mother read to us every night…

In addition to their considerable contributions to the sustenance of family, and the running of homes and farms, women throughout the past century and a half or more have taken up paid work outside the home. Women spoke of their grandmothers running general stores for timber camps, or serving as the sole postal worker for tiny post offices throughout the hills. Some women worked in early hotels and boarding houses, cooking and cleaning; in later decades they worked in restaurants and theaters. Less common, perhaps, were women who had more professional jobs in town, such as working in the family bank. In the present, of course, women work in all sectors, and are in many cases the sole or primary income earner for the family. Add to this the fact that some of them also work on degrees of higher education, while raising children and working at their jobs, and we see that the hard work ethic of the past burns just as fiercely in women of today.

Communities of Faith

For the majority of people living in the Missouri Ozarks, religion is a central feature of their lives. Church and faith offer some of the bonds that have historically held families and communities together, and this is largely still true today. The most predominant church found in the region is Southern Baptist. There are also a number of Methodist and Lutheran churches, a fair number of Pentecostal churches, and a few smaller congregations of Catholic, Mennonite, Jehovah's Witness and Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. The church, regardless of denomination, has served a number of functions for people. Church offers a time and place to solidify faith in God, provides moral and aesthetic foundations for hard work, and offers teachings and doctrines that guided the socialization and moral training of the young. Quite significantly, the church has always also provided a centralized meeting place for people not only to worship together but to socialize with one another. Churches were and still are an extremely important center around which all sorts of social activities take place, from the old "dinner on the grounds" to contemporary "Italian dinners" or pancake breakfasts, as well as bible study and services (Bellou 2001).

River baptism, Cultural Resources archives, n.d.

Many women we interviewed noted the central role of the church in providing a moral foundation for themselves and for their children. As one woman said, "[I]t makes you a much better person…The closer you get to God, the better you're gonna be…in everything you do."

Almost all of the churches in the region are headed by men in the roles of priest, preacher, minister, or deacon, and very few women are interested in pursuing formal leadership roles. As one woman in an Assembly of God church put it, "Women can be deacons…but the area we're in, people frown on that." Another woman added, "That's not part of the doctrine, it's a part of the culture" (quoted in Bellou 2001: 13). Still, women's leadership is central and extensive in all church congregations. Males in leadership positions admit to the centrality of women's work in the church, and women themselves clearly recognize that without them, church communities would fall apart. This is true in terms of organizing, cooking for, setting up and cleaning up after social events; teaching Sunday school to children and Bible school to adults; keeping churches clean and decorated; and celebrating special days of the church calendar, among other things. But women also contribute in the rhythm and flow of Sunday services through playing music, leading and singing in choirs, ushering, greeting and so on. Women directly support the central figure of the male church leader in dozens of ways, and they draw a strong sense of empowerment from their roles in the church (Bellou 2001; Waal, Carla and Barbara Oliver Korner 1997; Hardesty 1984).

A relationship with forces larger than themselves have helped people to explain sudden death, years of drought, and countless other hardships. Contemporary efforts to maintain a strong sense of family and a moral context for raising children continue to be pursued through daily prayer and Sunday worship. For decades women have turned to prayer in difficult and joyful times. For many, faith in God is the backdrop to all that they do in the rest of their busy days. And coming together as communities of faith is at the heart of a larger sense of cohesion and continuity shared by most residents of these Ozark hills.

Changing Times

Women who range in age from fifty up through their nineties can easily remember the hard working times of the past. And many of them have seen changes that range from the installation of indoor plumbing, to electricity, telephones, computers and the internet all in their lifetimes. Elderly women spoke with mixed feelings about the changes they have seen. Undoubtedly, those who have lived through the last several decades have seen more change than humans of any previous century. Changes in transportation and communications technologies have affected them on many levels. Improvements in roads and use of automobiles have meant greater personal mobility; at the same time, massive transport of goods made available at large department stores or convenience stores means an almost complete reliance on the market and, in many cases a reduced quality in nutrition. Appliances, electricity and telephones radically changed the way house and farm work was done.

Along with material changes came changes in priorities about lifestyle and moral values. Many women, for example, were saddened by the relatively small amount of time their children and grandchildren spent outside. Church communities are still of central importance in most women's lives, but women spoke of shifts in the ways that people now focus more on their nuclear families, and less on others in the community. The lessening of a sheer demand for help with hard physical labor has meant folks may no longer have good reason to go visit neighbors. Women remember with fondness the enjoyment of hard work together, shared neighborhood entertainment, and a sense of community in the past. Yet they also value the changes in technology and economy that their region has seen. For the most part, they have nicer homes, appliances to ease the work, and a few more luxuries than in the past. While they may be nostalgic about hard work of the past, they do not wish to return to it.

Gender Specific Use of the Park

OZAR Cultural Resources archives photo, n.d.

The ways that men and women may interacted with the lands and waters of the riverway sometimes reflects gender roles played out in other areas of life. In the past, women gathered berries, greens, nuts, and herbs, providing food and medicines for their families. In the past as in the present, men hunt and fish in favorite camping spots, and women sometimes join them for this. While men go out fishing together, women might cook on the sand bars. Children have always played along the rivers and in the woods. Women are almost always the primary caretakers for children, even on leisurely outings. And preparation for and clean up from such trips was also often women's work.

People noted changes in technologies such as larger boats and cars meant that women and children could enjoy trips on the river that had previously been made by men only. A few women joked that some husbands would use their family as a reason to purchase a bigger or more powerful boat.

In contemporary river use, women are more likely to accompany their children to swimming holes during the day, or to take them to one of the historic sites as a day outing. Thus, women and men may have different knowledge of various Park areas. And local residents overall use the park in ways that visiting tourists do not. Locals utilize primitive camp sites on rough little roads that do not even appear on Park maps, and which outsiders are not likely to find; conversely, they are much less likely to stay at a paid camp site. Overlaying maps of use areas would show many mutually exclusive sites of activity. Local people's sense of the rivers and their significance is fundamentally different from understandings by visiting tourists.

In this sense, the entire Riverway has long been of significance to local residents. People have attachment to certain special spots, but also to the flowing rivers as a whole. These residents of the Southern Missouri Ozarks meet the requirements for being identified as Traditionally Associated Peoples (Management Policies 2001; NPS #28). They have lived in the region for many generations, they have a strong attachment to and subsistence reliance on the Riverway environment, and it is central to their cultural identity. All of this was true long before the OZAR was established. On a scale that is much larger than the few very special springs along the Riverway, the corridor of river and contiguous lands is significant as a whole (Evans, Roberts and Nelson 2001). Indeed, perhaps the controversy over the formation of the Park would not have been so heated were it not for people's strong sense of attachment to this place.

The Significance of Gender

Gender is a central element to human identity, and is variously constructed in different cultural areas. What gets determined to be women's work, for example, is not somehow naturally apparent, but is something assigned to women by their particular culture. In the Ozark hills, gender is understood in ways particular to the culture of this area. Other features such as ethnic background, race, religion, and class contribute to conceptualizations of gender identity. Of course, not all women are alike. Even within one cultural region, there will be a fair amount of variation in how women and men think and behave. This larger research project focused on both what is shared by most women in this region of the Ozarks, as well as their particularities. Ranging across what is shared and what is unique to these women, the project considers how they are attached to, interact with, derive meaning from and identify with their local landscapes.

This project is an exemplary case of research undertaken by the National Park Service in order to better understand Park-related communities. Women's lives have typically been given less attention in the historical and cultural record. Yet, of course women's experiences are as central to the unfolding of human events—if not even more pivotal, in some cases—as men's. There is great need for uncovering and highlighting the history and contemporary experiences of women, and doing so in careful ethnographic detail (Scott 1988). By investigating women's past and contemporary lives in the OZAR area, the Park can consider ways to better represent those historical lives, and to better integrate with contemporary women's and men's experiences, whether local residents, visitors, or NPS staff.

Bibliography

-

Bellou, Tina

- 2001 Women and Religion in the Ozarks. Research paper for Women of the Ozarks course, Hendrix College, spring term 2001.

-

Gaul, Karen and Corey Lashlee

- 2001 Women of the Riverways: Special Emphasis Ethnography for the Ozark National Scenic Riverway. Report prepared for the National Park Service, Midwest Region, Contract No. 1433CX200099012.

-

Gerlach, Russell L.

- 1984 "The Ozarks Scotch-Irish: The Subconscious Persistence of Ethnic Culture." P.A.S.T. Pioneer America Society Transactions 7: 47-57

-

Gibson, Jane

- 2000 Living By the Land and Rivers of the Southeastern Missouri Ozarks. National Park Service, Ozark National Scenic Riverways.

-

Hall, Leonard

- 1958 Stars Upstream: Life along an Ozark River. Chicago: the University of Chicago Press.

-

Hardesty, Nancy

- 1984 Women Called to Witness. Abingdon Press.

-

McNeil, W K.

- 1995 Ozark Country. Folklife in the South Series. Jac

-

Beveridge, Thomas

- 1990 Geologic Wonders and Curiosities of Missouri. Rolla, MO: Missouri Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geology and Land Survey

- Director's Order #28: Cultural Resource Management

-

Evans, Michael J, Alexa Roberts and Peggy Nelson

- 2001 Ethnographic Landscapes. Cultural Resource Management, vol. 24, no 5. p. 53-55, MI: University Press of Mississippi.

- National Park Service Management Policies 2001

-

Parker, Jane H.

- 1992 Engendering Identitie[s] in a Rural Arkansas Ozark Community. Anthropological Quarterly. July [65] 3, 148-156

-

Rhodes, Richard

- 1974 The Ozarks: The American Wilderness. Time-Life Books: Alexandria, Virginia.

-

Scott, Joan Wallach

- 1988 Gender and the Politics of History. New York: Columbia University Press.

-

Stevens, Donald L.

- 1991 A Homeland and a Hinterland: The Current and Jacks Fork Riverways. Historic Resource Study, Ozark National Scenic Riverway. National Park Service.

-

Zedeno, Maria Nieves and Robert Christopher Basaldu

- 2002 Ozarks National Scenic Riverways, Missouri Cultural Affiliation Study. Bureau of Applied Research in Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, for the National Park Service, Task Agreement No. 04 for Cooperative Agreement No. H8601010007.