African Systems of Meaning

People express cultural meaning through their sacred and secular rites, ceremonies, rituals, art, music, dance, personal adornment, celebrations and many other socio-cultural customs and practices. However, language is the primary means through which they communicate what they think, believe, imagine, and understand.

Language

For the first generations of Africans enslaved in the colonies, language accommodation and acculturation were a necessity for their survival in the Western world. Depending upon when and where they came from in Africa, in addition to their own languages, different African people had varying degrees of language competence in English, Spanish, Portuguese and Dutch. As a concomitant of trade with Portuguese in the mid-fifteenth century, bilingualism arose among West Africans along the coast. In succeeding centuries, as West Africans traded with the Dutch, French and English, some Africans continued to at least understand, and many to speak, some form of one or more European languages. Even though they spoke many different African languages, many Africans who had participated in long distance trading on the African continent spoke a “lingua franca” or trade language that allowed them to communicate among themselves (Abrahams 1983:26). African sailors on European vessels may have also spoken a “maritime jargon (Berlin 1998; Birmingham 1981; McWhorter 1997, 2000a).” The first generations of Africans and Europeans coming in contact, like all people of different language groups, spoke their own language and developed a pidgin, language. Pidgins included words and meaning from both languages that allowed them to communicate. Pidgin has no native speakers.

Over time, both Africans and Europeans communicated in some form of creole. People of Angola and West Central Africa developed Angolar Creole Portuguese, a language still spoken by descendants of maroon slaves who escaped from Portuguese plantations on São Tomé beginning in the mid 16th century (1535–1550). People who were enslaved by the Spanish developed Spanish-based creoles, called Papiamentu Creole Spanish. Palenquero is another Spanish creole developed by Africans in maroon settlements of what is now Colombia, South America. Enslaved Africans in New Netherlands, later New York, developed a Dutch-based creole, Negerhollands Creole Dutch, in Haiti and later in Louisiana people spoke a French-based creole, today called Haitian Creole French. In the English colonies Africans spoke an English-based Atlantic Creole, generally called plantation creole. Low Country Africans spoke an English-based creole that came to be called Gullah. Gullah is a language closely related to Krio a creole spoken in Sierra Leone.

African Creoles Languages

| Location of Enslavement/ African People | European Contact Language | Creole | Spoken Language 21st century? |

| Settlements of Maroons from São Tomé | Portuguese | Angolar Creole Portuguese | Yes |

| Viceroyalty of New Spain (Mexico), Surinam, Aruba, Bonaire, Curacao | Spanish | Papiamentu Creole Spanish | Mexico? Surinam, Aruba, Bonaire, Curacao Yes |

| Maroon settlements in Vice Royalty of Peru (Colombia) | Spanish | Palenquero or Palenque | Yes 2500 speakers in 1989 |

| New Netherlands 17th century Virgin Islands 18th century forward | Dutch | Negrerhollands Creole Dutch | No, last speaker in Virgin Islands died in 1987 |

| Haiti Louisiana |

French | Haitian Creole French | Yes |

| Atlantic Sea Coast Low Country | English | Gullah | Yes |

| Sierra Leone | English | Krio | Yes |

(Hancock 1992; Holm 1989)

Enslaved African American Language

According to the limited access model of creole language development, Gullah and other creoles emerged because enslaved Africans greatly outnumbered Whites on colonial plantations as occurred in the Low Country, especially in the Sea Islands where a particular form of plantation creole called Gullah developed. McWhorter advances an “Afrogenesis Theory”of creole origins, stressing the importation of most plantation creoles from West African trade settlements. There creole languages originated in interactions between white traders and slaves, some of whom were eventually transported overseas (McWhorter 2000a, 2000b). The Afrogenesis Theory helps explain why Gullah and Krio are similar creoles.

Walsh notes that, “Gullah,” attained creole status during the first decades of the 1700s, and was learned and used by the second generation of slaves as their mother tongue. Around the same time, in the 1720 and 1730s, Anglican clergy were still reporting that Africans spoke little or not English but stood around in groups talking among themselves in “strange languages (Walsh 1997:96–97).”

In the past, enslaved Africans from Jacksonville, North Carolina to Jacksonville, Florida along the coast and 100 miles inland spoke Gullah. In the present, many of the descendants of the early Gullah speakers continue to speak a form of the language (Hancock 1992:70–72; Geraty 1997). African American heritage preservation efforts in the Sea Islands include attempts to maintain Gullah as a living language.

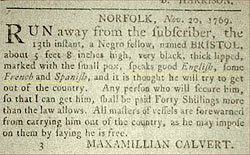

Runaway advertisements noted enslaved people’s distinctive language characteristics and level of language proficiency as identifiers. A search of runaway advertisements 1736–1776 in the Virginia Gazette, Williamsburg, Virginia yielded advertisements for (5) men described as “Angola negroes” or born in Angola. Two could speak very good English, two “speak English tolerably good” and one was described as stammering. Two advertisements identified “Eboe negroe.” One could “speak tolerable good English.” Jemmy, John and Boston in this image illustrate the range of English language competency among African-born men in 18th century Virginia.

As part of a more extensive study of comments on language found in runaways advertisements in 8 colonies/states, Gomez examined the quality of English spoken by 99 Africans in Virginia 1736–1836. He found that the advertisement’s descriptions said 39 Africans spoke “none, little or very little, 36 spoke “bad,” “very bad” or “broken” English and 24 spoke “good” or very good” English (1998:177–180).

According to Gomez, those African runaways 30 years of age or older or who had been in North America more than 3 years were most likely to speak good English. Like the Virginia Africans, over 70 percent of Africans running away from South Carolina, Georgia were also described as speaking “bad, very bad, very little, or no English.” Among Louisiana runaways, they were about equally divided between those who could speak French and those that could not. Gomez found the few women in the study were slightly more likely than the men to speak French or English (1998:179).

Many enslaved people were multi-lingual. “Without a doubt,” Morgan contends, “blacks were the most linguistically polyglot and proficient ethnic group in the Americas (2002:139).”

Africans and their American-born descendants who had frequent contact with American Indians also learned to speak their languages. Aside from shared enslavement, in the early settlement of the Southeast colonies, the cultures of Africans and American Indians intertwined in complex ways. In areas such as Southeastern Virginia, the “Low Country” of the Carolinas, and around “Galphintown” near Savannah, Georgia, there were communities of Afro-Indians born of intermarriage between enslaved African men and enslaved Indian women. Galphin, who was Irish, was a prominent Indian trader in the Creek Nation and Indian Agent for the First Continental Congress. He used African Americans as scouts, translators and laborers in his trade with the Five Nations of the Southeastern United States (Forbes 1993:225–228; Mingues 1999).

The continuous arrival of “salt-water” Africans influenced the language spoken by American-born Africans in the rural colonial Chesapeake and Low Country regions up until 1807. Even after this date, smugglers sold Africans in the region, right up until the Civil War (Kashif 2001). In contrast, many free African Americans in the Southern colonies became more acculturated in speech and literate, along with all other European cultural customs, as they consciously sought to differentiate themselves from their enslaved sisters and brothers.

Language Performance

Beyond linguistic competence in grammar and vocabulary, language performance by enslaved people continued to incorporate characteristic African elements in language performance. In African and African American societies eloquent delivery of speech is highly valued. Peer respect and admiration are garnered by people who are witty, can speak broadly about many subjects, use devices such as rhyming, switch back and forth between vernacular and standard language (Abrahams 1983:21–25). Bryan Edwards writing in the late 18th century about “Negroes” in Jamaica commented:

“Among other propensities and qualities of the Negroes must not be omitted their loquaciousness. They are fond of exhibiting set speeches, as orators by profession; but it requires a considerable patience to hear him throughout; for they commonly make a long preface before they come to a point; beginning with a tedious enumeration of their past services and hardships (Edwards 1793:78–79).

Here Edwards refers to what others have called “indirection” in language performance. Use of an intermediary, that is attributing remarks to a third party even a fictitious one such as “Brer Rabbit” is another characteristic of African influenced speech performance (Morgan 1991; Brown 1999). Use of proverbs and double entendre are other language performance characteristics found among speakers of African descent. Edwards describes one such instance:

[A] servant brought me a letter and, while I was preparing an answer, had through weariness and fatigue, fallen asleep on the floor…I directed him to be awakened….When the Negro who attempted to wake him exclaimed in the usual jargon, You no hear Massa call you?” “Sleep” replied the poor fellow looking up, and returning composedly to his slumbers…“Sleep has no Massa”. (Edwards 1793:78–79).

Runaway slave advertisements frequently describe English speakers as artful, sly, and impudent, in their speech. Read more about African and African American language and language performance.

Language and Worldview: Time

Through the use of language and its meaning, people express their cultural world view. For example, the English viewed time as mechanical and a measurable asset. They spoke of using time “wisely,” “wasting” time” and “saving” time. The English recorded the past as a history stretching back to antiquity. They recorded births in bibles and other written documents.

Apparently descendant generations of enslaved people were slow to acculturate to English concepts of time. African’s use of time was one of the greatest criticisms by slave owners. They wanted them to change their perception of time and work.

Some West Africans recorded the birth of their children by naming them after the day of the week they were born, others associated the year of their birth with a natural event. Vass and others report enslaved African and African-Americans continued the practice of naming their children after days of the week, months, and seasons (Hollaway and Vass 1993:80–81). West Africans conceptualized time in terms of nature and the passage of seasons. Passage of long periods of time were not measured, at least not precisely but rather “located” in association with some seasonal variation in nature, like the dry or rainy season or in relation to significant physical or social events, as in the time of a great flood. Sandy, a runaway in 1768 told the sheriff he had “made two crops for his master” and that he had been a runaway for “two moons.” Other accounts suggest Africans as well as and their descendant generations, were slow to acculturate to English concepts of time, for example the rare 18th century autobiography of “Old Dick” born to African parents enslaved in Virginia describes him as saying: “I was born at a plantation on the Rappahannoc [sic] River. It was the corn pulling time, when Squire Musgrove was Governor of Virginia (Sobel 1988:33).”

Time in the Akan systems of meaning is conceptualized as a merger of the past and present into an enormous present (Adjaye, 1994:72). These kinds of ideas persist among contemporary Akan (Twi-Fante) groups from areas in Africa that were the source of large numbers of people enslaved in the southern colonies (Brown 1995).

The so called “Kongos” and “Angolas,” Bantu peoples, held similar perceptions of time. In the Bantu people’s systems of meaning the past goes and returns to people in the present time, the future is tomorrow’s past, so that the future, present, and past are one (Fu-Kiah 1994). Religious music and prayers of present day descendants of enslaved South Carolinians express similar ideas (Brown 1995). Enslaved Africans resisted acculturation of their time orientation. Instead, they incorporated African meanings for time into their Creole language, and into aspects of their sacred cultural performances. Some African Americans continue such performances in the present. Read more about Time, Language and Worldview.

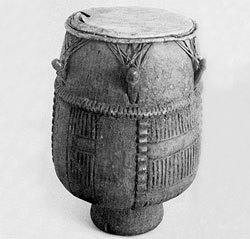

Night was a traditional time for celebrations in Africa. In 18th century Gambia, for example, people were observed to dance to the drums and other instruments, all through the night and sometimes for as long as twenty-four hours. As early as 1688 Governor Nicholson of Maryland noted that slaves commonly traveled long distances on Saturday nights, Sundays and around Christian holidays to visit one another. Whenever possible Africans “took time,” usually at night. This was “time” they used for hunting, dancing, funerals, and religious ceremonies (Sobel 1988:33).

Colonial accounts describe African performance of culture in the dance, music, and religious ceremonies of the day. Artifacts and human remains found in archeological excavations yield further insights into colonial African funerary practices and secret rituals.