Guidelines for Rehabilitating Cultural Landscapes

Vegetation

Identify, Retain, and Preserve Historic Features and Materials

![]()

Identifying, retaining and preserving the existing historic vegetation prior to project work. For example, woodlands, forests, trees, shrubs, crops, meadows, planting beds, vines and ground covers. Documenting broad cover types, genus, species, caliper, and/or size, as well as color, scale, form and texture.

Evaluating the condition and determining the age of vegetation. For example, tree coring to determine age.

Retaining and perpetuating vegetation through propagation of existing plants. Methods include seed collection and genetic stock cuttings from existing materials to preserve the genetic pool.

![]()

Undertaking project work that impacts vegetation without executing an existing conditions survey of plant material.

Undertaking project work without understanding the significance of vegetation. For example, removing roadside trees for utility installations, or indiscriminate clearing of a woodland understory.

Failing to propagate vegetation from extant genetic stock, when few or no known sources or replacements are available.

Protect and Maintain Historic Features and Materials

![]()

Protecting and maintaining historic vegetation by use of non-destructive methods and daily, seasonal and cyclical tasks. For example, employing pruning or the careful use of herbicides on historic fruit trees.

Utilizing maintenance practices which respect the habit, form, color, texture, bloom, fruit, fragrance, scale and context of historic vegetation.

Utilizing historic horticultural and agricultural maintenance practices when those techniques are critical to maintaining the historic character of the vegetation. For example, the manual removal of dead flowers to ensure continuous bloom.

![]()

Failing to undertake preventive maintenance of vegetation.

Utilizing maintenance practices and techniques which are harmful to vegetation; for example, over- or under-

irrigating.

Utilizing maintenance practices and techniques that fail to recognize the uniqueness of individual plant materials. For example, utilizing soil amendments which may alter flower color or, poorly-timed pruning and/or application of insecticide which may alter fruit production.

Employing contemporary practices when traditional or historic can be used. For example, utilizing non-traditional harvesting practices when traditional practices are still feasible.

Repair Historic Features and Materials

![]()

Rejuvenating historic vegetation by corrective pruning, deep root fertilizing, aerating soil, renewing seasonal plantings and/or grafting onto historic genetic root stock.

![]()

Replacing or destroying vegetation when rejuvenation is possible. For example, removing a deformed or damaged plant when corrective pruning may be employed.

Replace Deteriorated Historic Materials and Features

![]()

Using physical evidence of composition, form, and habit to replace a deteriorated, or declining, vegetation feature. If using the same kind of material is not technically, economically, or environmentally feasible, then a compatible substitute material may be considered. For example, replacing a diseased sentinel tree in a meadow with a disease resistant tree of similar type, form, shape and scale.

![]()

Removing deteriorated historic vegetation and not replacing it, or replacing it with a new feature that does not convey the same visual appearance. For example, a large mature, declining canopy tree with a dwarf ornamental flowering tree.

Design for the Replacement of Missing Historic Features

![]()

Designing and installing new vegetation features when the historic feature is completely missing. It may be an accurate restoration using historical, pictorial and physical documentation; or be a new design that is compatible with the habit, form, color, texture, bloom, fruit, fragrance, scale and context of the historic vegetation. For example, replacing a lost vineyard with more hardy stock similar to the historic.

![]()

Creating a false historical appearance because the replaced feature is based on insufficient historical, pictorial and physical documentation.

Introducing new replacement vegetation that is incompatible with the historic character of the landscape.

Alterations/Additions for the New Use

![]()

Designing a compatible new vegetation feature when required by the new use to assure the preservation of the historic character of the landscape. For example, designing and installing a hedge that is compatible with the historic character of the landscape to screen new construction.

![]()

Placing a new feature where it may cause damage or is incompatible with the character of the historic vegetation. For example, constructing a new building that adversely affects the root systems of historic vegetation.

Locating any new vegetation feature in such a way that it detracts from or alters the historic vegetation. For example, introducing exotic species in a landscape that was historically comprised of indigenous plants.

Introducing a new vegetation feature in an appropriate location, which is visually incompatible in terms of its habit, form, color, texture, bloom, fruit, fragrance, scale or context.

The Star-Fort at the Ninety-Six Battlefield, Ninety-Six, South Carolina, was eroding from mowing operations. [left] To remedy the situation, native grasses were installed on the historic Revolutionary War Star Fort. [right]. The interior of the fort has been mown short to accommodate visitor access, but tall native grasses are kept longer on the earthworks to discourage visitors from walking on them and to aid in their interpretation. The difference in height of the new grasses also help to visually define the earthworks themselves. ( NPS)

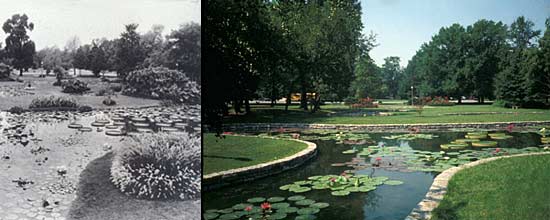

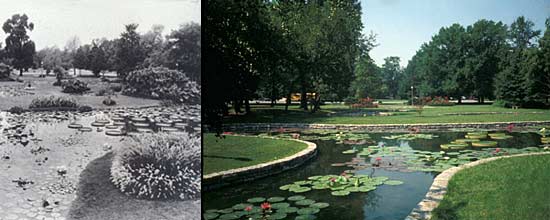

Tower Grove Park in St. Louis, Missouri, is a National Historic Landmark. The Victorian park, famous for its ornamental herbaceous beds, or “bedding-out,” [top,left] had all but lost most of these areas of seasonal plant display to mown lawn for ease of maintenance. [top, right] More recently, these beds have been reinstated using historic photographic documentation and written accounts. The results are herbaceous beds that are of a new design that is compatible with the habit, form, color, texture, scale, massing and context of the historic vegetation. [below] (Tower Grove Park)