|

Visitors to the Platt Historic District find a remarkable and inviting landscape of swimming holes, winding trails and roads, campgrounds, and rustic stone buildings that provide a quiet, intimate place to relax and explore the natural environment. These features reflect the hard work of young men whose lives were changed by an organization that lasted only nine years but left an indelible mark on the landscape of the United States. These “Men Who Built the Parks” left a legacy in parks and forests across the country, and decades later, millions of people still enjoy their work. A Troubled EconomyMany people who had enjoyed the prosperity of the Roaring Twenties found themselves in soup lines and tattered clothes by the early 1930s. Sputtering Model Ts rumbled down dusty roads, carrying passengers and their few possessions toward dreams of a better tomorrow. The growing depression devastated the nation’s economy and left many in dire straits. By 1933, nearly ten thousand banks had failed and more than 16 million Americans were unemployed. Fifteen percent fewer children were born in 1933 than in 1929; a reflection of severely diminished expectations. Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) was elected president by a landslide in 1932 with his promise of a “New Deal” for the American people. Within days of his inauguration, FDR called Congress into special session to work on emergency legislation to aid the economy and the American people. Many new agencies and programs were created to provide relief and restore the economy. President Roosevelt kept his promise and the New Deal was born.

NPS Photo Roosevelt’s “Tree Army”Probably the most popular New Deal program was the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). Designed to reduce unemployment while also conserving natural resources, the CCC affected the lives of millions of Americans, and transformed the American landscape. Nicknamed “Roosevelt’s Tree Army,” the CCC was operated through the cooperative efforts of four departments. The Department of Labor oversaw the selection of enrollees, the Army ran the camps, and the Interior and Agriculture departments provided work projects. The work of the CCC initially focused on reforestation, but quickly evolved to include soil conservation and development of recreational park facilities. Initially, unmarried men between the ages of 18 and 25 whose families were on relief could apply. They enrolled for six months, with an option to reenlist for up to two years. Enrollees earned $30 a month, $25 of which was sent to their families. Eventually, “Local Experienced Men” and World War I veterans were allowed to enroll. African-Americans and American Indians also participated, generally in segregated CCC companies.

NPS Photo A New Deal for Platt National ParkFrom 1906 until 1976 the present-day Platt Historic District was known as Platt National Park. Established as Sulphur Springs Reservation in 1902 to protect mineral springs and water resources, the site evolved from a settlement and town site into a national park. This evolution required almost equal amounts of obliteration and construction of buildings, roads, and other features. The early appearance of Platt National Park was not what we imagine today when we think of national parks. Early park features included not only mineral springs, but flower beds, animal pens, and a golf course. The small size and humble resources of Platt National Park were somewhat atypical, when compared to the great landscape parks with their sublime scenery and monumental hotels. Yet visitors didn’t seem to notice; in 1914, Platt’s visitation exceeded that of both Yellowstone and Yosemite and was second only to the Hot Springs Reservation in Arkansas. Because of its limited size and the unusually large number of visitors, portions of Platt were heavily impacted by camping, cars, and people. Balancing visitor needs while protecting park resources was a constant struggle in the early years of Platt National Park. The programs and federal dollars of the New Deal were seen as “a golden opportunity” by park staff.

NPS Photo Camp and CommunityThe community of Sulphur had some apprehension about a CCC camp, concerned over the possible presence of unruly young men. This attitude swiftly changed as the camp was established and work began. The city demonstrated their appreciation in 1935, by donating thirty gallons of paint to improve the appearance of the camp buildings. Enrollee Earl Pollard remembered, “Sulphur used to be a lively place. Very lively. The camp didn’t have any air conditioning, and we’d open the windows and doors at night, and the music from the honky tonk would put us to sleep every night.” Camp facilities included a headquarters building, day room, and a little canteen where enrollees could buy cigarettes, gum, and candy; in the middle of the camp were a shop, educational and supply buildings. Two barracks, a latrine, and a mess hall were on the west end. Three more barracks were located on the south side and a flagpole in the parade ground. The camp cook would prepare hot lunches, including sliced pies, which were brought into the field to feed work crews. Company 808’s masonry, forestry, and landscaping work was exemplary, but the development of the young men “mentally, physically and morally” was the most outstanding part of the program. Enrollee Jay Pinkston remembered working “harder in Platt National Park than I ever worked for any contractor or expected to.” In June 1940, after eight years of work, Company 808 moved from Platt National Park to Rocky Mountain National Park. When the CCC boys left, one writer remembered, “a feeling like that accompanying an irreparable loss settled on the community.”

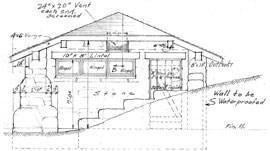

NPS/Chickasaw National Recreation Area "Improving" NatureBetween 1933-1940, a series of landscapes—including spring pavilions, creek dams, swimming holes, wooded picnic grounds, hiking trails, a new road system, and campgrounds—were created or improved with the labor of the CCC in Platt National Park. Old restrooms, roads, and other features were removed and the land rehabilitated. Master planning treated the landscape as a whole, enhancing and revealing its natural, geological, and water-based marvels, while providing for visitor recreation in and enjoyment of nature. Constructed of native materials, the resulting New Deal landscape of Platt National Park is of exceptional quality and demonstrates outstanding workmanship that has proven extremely durable. According to CCC mason Frank Beaver, soil and rock was removed from the front of Antelope Springs to reveal the fresh water spring emerging from the solid rock formation below. Enrollee Earl Pollard commented that, “The construction supervisor said that all landscaping was ‘nature faking.’ The shoulders had been graded and they wanted to make it grow back natural.” Enrollee Truman Cobb commented that he “took care of those slopes. They put us to doin’ somthin’ that would last, and make something beautiful. You go today, where they’re building highways and it’s just an old barren cut there and nothin’ pretty about it. But we sloped those things, leaving the boulders, leaving the outcroppings that would be picturesque…. We might work half a day around one boulder… kinda like an artist” The CCC planted 800,000 plants, including 60 tree species throughout Platt National Park. Enrollee Delbert Gilbert, who served on the ‘sapling crew’ remembered, “They schooled us on not hurting the trees. Don’t break no green limbs off, you know, and we took that schooling.” Although the Platt Historic District’s landscape features—stone bridges and culverts, scenic vistas, rustic buildings constructed of native limestone, and plantings of cedars and wildflowers—are important individually, together they compose a cohesive and seemingly natural recreational environment. Thus the CCC design of Platt National Park transformed an eroded resort landscape into a holistic place of great beauty, whose enduring recreational and scenic values visitors still experience and appreciate today. The LegacyNationwide, the CCC operated 4,500 camps in national parks and forests as well as state and community parks. More than three million men enrolled between 1933 and 1942, planting three billion trees, protecting 20 million acres from soil erosion, and aiding in the establishment of 800 state parks. The CCC advanced natural resource conservation in this country by decades, and provided education, training, and experience for a generation of young men. Remembering the work of the CCC at Platt National Park, enrollee Truman Cobb observed that, “all of the pavilions are just kind of monuments to some real good construction work. Even the restrooms are made with permanence….” Millions of visitors to the Platt Historic District have enjoyed the work of the CCC. During your visit take a drive along the perimeter road, hike the trails along Travertine Creek or through Flower Park, and remember the young men who worked there many years ago. As Arthur M. Schlesinger, Jr., wrote, the Civilian Conservation Corps has “left its monuments in the preservation and purification of the land, the water, the forests, and the young men of America.” To learn more:

|

Last updated: February 16, 2021