NPS

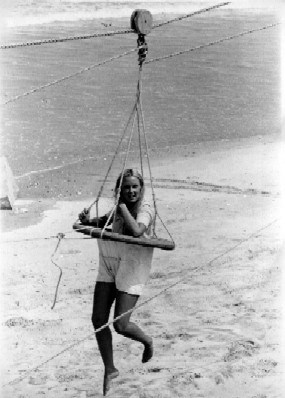

NPS The beach apparatus or breeches buoy was a fairly common rescue technique utilized by the US Life-Saving Service on the Outer Banks since so many of the shipwrecks occurred near or on the beach or in seas that prohibited the use of the surfboat. To effectively use the breeches buoy took skill and timing. Surfmen practiced it in their Beach Apparatus Drill each week. Each man had to know exactly what to do at the proper time or the entire rescue would become a disaster. The first step was to send a line, called the shot line, out to the shipwreck, using a projectile fired from a line-throwing gun known as the Lyle gun. With its wooden carriage, the Lyle gun weighed almost 200 pounds and had to be taken out to the shipwreck in the beach cart along with all the other required equipment. This gun could fire a 20 pound metal projectile with a line attached to it up to 400 yards. It was aimed simply by line of sight and elevated by a stepped wooden block called a quoin. The idea was to establish an initial means of communication with the wreck so that equipment could then be sent out and the breeches buoy rigged up. This was not as easy as it might sound, however. Wind, rain, snow, fog, darkness, and the wreck’s position could all affect the accuracy of the shot and, even if the line reached the target, it could still become entangled in the debris. It often took several shots to achieve success but sometimes the conditions were simply too severe. The lifesavers were then forced to wait until conditions improved enough for a successful shot or until a boat could be launched. It was every ship captain’s responsibility to have his vessel and crew prepared in the event of a disaster and instructions were distributed that explained what to do in a rescue attempt by the US Life-Saving Service. The most important of thing those on the wreck had to know was to pull in the shot line when it reached their vessel. The lifesavers attached another line with a pulley on it to their end of the shot line but they could do nothing more until this was pulled out by those on the wreck and secured to a mast. There were times when the captain or the men on the wreck did not meet this critical responsibility due to fatigue or ignorance. Many shipwreck tragedies could have been averted if only this necessity had been realized. Other important aspects of the beach apparatus procedure included securing the breeches buoy line or hawser to a wooden anchor buried in the sand, using block and tackle to maintain tension on it, and keeping it above the water using a wooden prop called a crotch. Only then could the breeches buoy be sent out and the survivors pulled to safety one at a time.

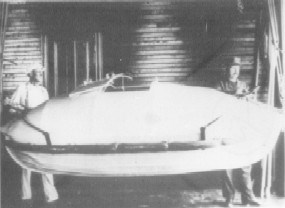

Circumstances such as extremely rough seas or a wreck at a substantial distance from shore made the use of the breeches buoy impractical since it put the person being rescued at risk of drowning. In such situations, the surfmen could instead employ the lifecar, a cigar-shaped metal device with room inside for several people. Though claustrophobic and uncomfortable, the enclosed compartment protected survivors from the dangers outside as it was pulled across the water. Problems with the lifecar included its excessive weight, the strain on the hawser line, and the limited breathable air inside. But the advantages of protection and the number of people that could be transported at one time often outweighed these disadvantages and the lifecar became a favored lifesaving method when there was a large number of people to be rescued. The breeches buoy and lifecar may appear to be rather peculiar forms of lifesaving but they worked very well; thousands of lives were saved through their use. This method of lifesaving continued in practice with the US Coast Guard until replaced by the helicopter as a means of rescue in the 1950s. |

Last updated: April 14, 2015