When you think of migrating animals, what do you envision? Birds flying north in the spring? How about great herds of zebras, antelopes, and other hooved animals navigating the African plains? Or maybe salmon leaping upstream to the place they were spawned? During the months of December through March, we at Cabrillo National Monument are fortunate to witness one of the longest animal migrations in the world – that of the Pacific Gray Whale (Eschrichtius robustus). “Robustus” means “strong” in Latin, which is an apt description for these majestic marine mammals who make a pilgrimage from the Bering, Chuchki, and Beaufort Seas near Alaska all the way to Baja California and back again. But why, and how, do they manage this 10,000+ mile trek?

Photo courtesy of Pacific Beach Coalition – An adult Pacific Gray Whale breaches out of the water.

Photo courtesy of Pacific Beach Coalition – An adult Pacific Gray Whale breaches out of the water.

Infographic courtesy of Journey North.org – A map representing the 10,000+ mile migration of the Pacific Gray Whale.

Infographic courtesy of Journey North.org – A map representing the 10,000+ mile migration of the Pacific Gray Whale.

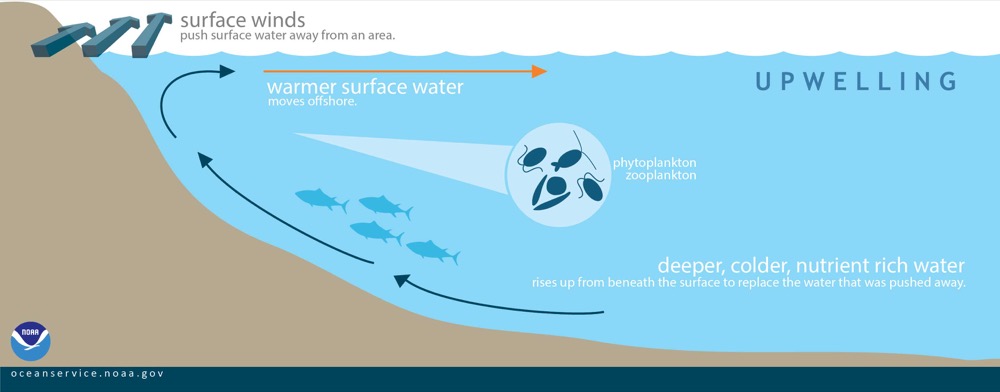

In the cold waters of the Arctic, there is a frequent phenomenon called upwelling that powers much of the species abundance and richness in the region. Upwelling is caused initially by wind – as wind blows over the surface of the ocean, water is pushed away, making space for colder water to rise up from the deep to take its place. This upwelling of colder, deeper water carries nutrients from the bottom of the ocean up to the surface, creating perfect conditions for plankton productivity. Where there is plankton, there is life – fish that feed upon the plankton, and creatures, like birds and dolphins, that feed upon the fish. Nutrient-dense waters like these are perfect for the Pacific Gray Whale – this species is a medium-sized baleen whale that dines primarily on planktonic species called amphipods. To feed, a Pacific Gray Whale first turns on its side and sucks the seafloor into its mouth, then it pushes the mud and silt back out again with its tongue, trapping amphipods and other plankton in its course baleen. While foraging, Pacific Gray Whales plow acres of mud which, in turn, releases nutrients trapped at the bottom into the water column – perpetuating the cycle of nutrients and abundance in these Arctic waters.

Infographic courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – A pictorial representation of “upwelling” – how water moves from the bottom to the surface, providing nutrients.

Infographic courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – A pictorial representation of “upwelling” – how water moves from the bottom to the surface, providing nutrients.

Photo courtesy of Hans Hillewart – A close-up shot of a tiny, shrimp-like creature called an amphipod.

Photo courtesy of Hans Hillewart – A close-up shot of a tiny, shrimp-like creature called an amphipod.

The summer months of foraging up north prepares these whales for their long journey south. The bounty of amphipods Pacific Gray Whales harvest is converted to enough blubber to sustain them for the migration to Baja and back again. But why leave such a robust food-source in the first place? The answer has to do with a couple of different factors. First, the shorter days of fall and winter negatively affect plankton abundance – less sunlight means there are fewer plankton for whales to dine upon. The second reason to migrate has to do with the life cycle of this whale species: the sheltered bays of Baja California are a safe haven for mating and birthing calves (baby whales).

Female Pacific Gray Whales endure a long pregnancy of 12 months, and then nurse their calves for approximately another 8 months, only weaning them after migrating back north. Calves need to drink around 50 gallons of high-fat milk a day to sustain their rapid growth and to prepare them for their first migration – a gray whale calf will double its birth weight by the time it’s weaned! After weaning her calf, the mother feasts on amphipods to build up that blubber once again – preparing to begin the cycle of migration, mating, pregnancy, and birth all over again.

As the migration is in full swing, we hope that you will grab your binoculars (or check them out for free at our visitor center) and make a migration of your own to Cabrillo National Monument for a peek at these majestic creatures. And we’re celebrating all things whale with an interesting and informative talk from Dr. Thomas Jefferson during our Naturally Speaking Lecture Series – this event will take place Thursday, April 4 at 6 p.m. and is open to any Cabrillo National Monument Foundation members or Volunteers! Learn more and RSVP at https://cnmf.org/event/how-to-spot-a-whale/

Photo courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – An aerial view of a Pacific Gray Whale mother and calf.

Photo courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – An aerial view of a Pacific Gray Whale mother and calf.

References

How upwelling happens:

https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/facts/upwelling.html

Pacific Gray Whale facts:

http://www.marinemammalcenter.org/education/marine-mammal-information/cetaceans/gray-whale.html

More Field Notes on the Pacific Gray Whale:

https://www.nps.gov/cabr/blogs/the-whale-diaries.htm

https://www.nps.gov/cabr/blogs/whales-on-the-horizon.htm

Naturally Speaking Lecture Series: