Liquid Gold Looking at Glenn Springs today, it is hard to imagine that anything ever happened here or that, in 1916, there were nearly 80 people living here in a busy little village. But history tells the tale of turbulence and violence that put Glenn Springs* on the map. It all begins with water—the "liquid gold" of the desert. Glenn Spring assumed its place in history because it was a reliable water source in an arid land. It lies on one branch of the Great Comanche Trail. Flint chips and bedrock mortar holes throughout the area indicate that Indians used Glenn Spring not only as a water stop during their raids into northern New Spain, but also for more permanent stops as well. The first Anglo settler was H.E. Glenn, who grazed a remuda of horses in the area. To provide a better water supply, Glenn dug out, and walled the largest spring. He was killed by Indians near the spring that bears his name. * According to noted historian Dr. Clifford Casey, the village was called Glenn Springs. The area itself is called Glenn Spring.

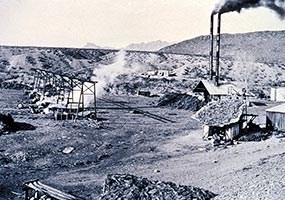

NPS Photo/Big Bend National Park The Wax Industry During the second decade of the 20th century, there were several ranches near Glenn Spring, and the village was a social center. In 1914, “Captain” C. D. Wood and Mr. W. K. Ellis built a factory near the spring to produce candelilla wax—another form of “liquid gold”. They employed 40–60 Mexican workers to operate the factory, and hired O.G. Compton to run the general store and post office. Candelilla, the wax plant, was the primary raw material needed for the wax business, and the Glenn Spring area not only had an abundance of the plant, but it also had water, another essential ingredient for the wax rendering process. Candelilla is a perennial plant, with hundreds of gray-green stems (each somewhat smaller in diameter than a pencil), which grow vertically from the base. Rendering wax from this plant was hard and hot work. In 1916, wax workers were paid $1.00 per day. The workers boiled the stems in large vats of water, adding sulfuric acid to separate the wax from the stems. When the wax floated to the surface, the men skimmed it off and boiled it again to remove excess water and impurities. They let it cool, broke it into small blocks and put it in burlap bags for shipping. Two boilers provided the steam to cook the wax. Dried, cooked plants were used as fuel to keep the boilers going. Processed candelilla wax is a very durable substance. It is still used in some quality shoe polishes, car waxes, chewing gum, and lip balm. More information on the wax industry along the Rio Grande... Glenn Springs Raid Bandit raids along the border initiated the U.S. government to send troops to the Big Bend region as early as 1911. On the warm summer night of May 5, 1916, there were nine soldiers stationed at Glenn Springs. Around 11:00 PM, after everyone had gone to bed, Mr. Compton, the storekeeper, was awakened by several armed Mexicans at his door. When they inquired if there were any soldiers in the village, he said no, hoping that they would go away. Compton was afraid they would return, however, and took his small daughter to a Mexican woman across the draw and asked her to keep the child for the night. He was returning for his nine-year-old son, Tommy, when the raid began. Captain Rodriguez Ramirez, a Mexican bandit, led his men into a dark, sleeping Glenn Springs, each man well-armed and shouting “Viva Carranza” and “Viva Villa” as he rode. How many Mexican raiders accompanied Ramirez or to whom they pledged their allegiance is not known. In Mexico during these unsettled times, it made little difference to the followers whether the leader was a Carranza or a Villa sympathizer, for political affiliations made little difference if the men were provided with food. Regardless of their numbers or affiliation, there were too many for the nine cavalrymen attempting to defend the village. These nine men of Troop A of the 14th Cavalry were sleeping in their tents when the bandits appeared. Upon hearing the shouts and commotion, they fled in the dark to an adobe building nearby where they would have more protection. For nearly three hours, the soldiers exchanged fire with the bandits and were able to hold off much of the attacking force. When the Mexican raiders realized that they were not making any headway they set fire to the thatched roof of the building. Pieces of the burning roof began to fall on the necks and heads of the men. As the oven-hot room filled with smoke someone yelled “run for it” and the soldiers fled from the adobe inferno to a nearby hill. Three of the soldiers were killed and all but two were either seriously wounded or badly burned. When Mr. Compton returned, he found that his son had been fatally shot. Mr. and Mrs. Ellis were awakened by the shooting and fled to the hills where they hid through the night. Captain Wood also heard the commotion at this home three miles away at Robbers Roost. At first, he thought it was the celebrations of Cinco de Mayo, but upon seeing the glow of the burning buildings, he and his neighber, Mr. Oscar de Montel, set out in the dark to see what was going on. They lost their way through the rough terrain and arrived after most of the shooting had ceased. Upon arriving, they were fired upon and quickly took cover till daybreak. The little community of Glenn Springs suffered heavy losses due to the raid: four people killed and four others severely injured, the store looted, two of the major buildings partially burned and much of the wax factory destroyed.

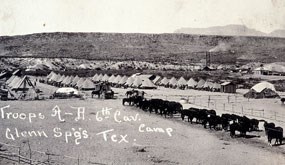

NPS Photo/Big Bend National Park The End Of Glenn Springs The Glenn Springs raid received national attention in major newspapers across the country. President Wilson issued orders for the mobilization of the Texas National Guard to aid federal forces along the border. A permanent cavalry camp was established at Glenn Springs in 1916 and remained until 1920, when the border situation improved. For three years after the raid, the rebuilt village persisted, but even with increased military support, it was difficult to find and keep good workers. After World War I, the price of wax plummeted and that seemed to be the last straw for Ellis and Wood. In 1919, they sold their property to a rancher named Burcham. When Ellis and Wood left, so did almost everyone else and the village dissolved. Other ranchers followed Burcham and the land changed hands many times until it was acquired by the State of Texas for donation to the Federal government for a national park. The spring remains—a golden flow of water in the desert, but little else remains as a reminder of the activities that once occurred here, or that fateful night of 1916.

NPS Photo/Big Bend National park To Learn More:

|

Last updated: September 1, 2020