Last updated: January 8, 2023

Article

Smith Court and the Underground Railroad

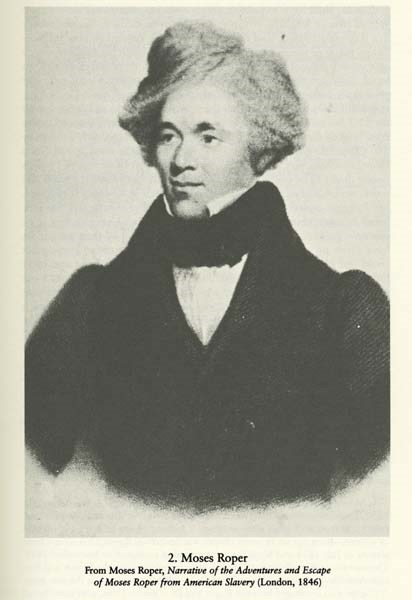

From Moses Roper, Narrative of the Adventures and Escape of Moses Roper from American Slavery (London, 1846).

In his 1837 Narrative of My Escape from Slavery, Moses Roper wrote:

During the first part of my abode in this city, I attended at the coloured church in Bellnap Street…After a time, I found slaveowners were in the habit of going to this coloured chapel to look for run-a-way slaves. I became alarmed…[1]

As home to the African Meeting House, the Smith School, and several private residences, Smith Court served as an integral center of Black life and activism in 19th century Boston. As indicated by Roper’s reference to the “coloured church in Bellnap Street,” it also played an important role in the history of the Underground Railroad in the city. According to historian Eric Foner:

The ‘underground railroad’ should be understood not as a single entity but as an umbrella term for local groups that employed numerous methods to assist fugitives, some public and entirely legal, some flagrant violations of the law.[2]

Boston’s Underground Railroad centered in the Black community of Beacon Hill and tied strongly to Smith Court. Those that escaped slavery sought sanctuary both in the church and in the homes along Smith Court. Activists rallied at the African Meeting House to protest the fugitive slave laws of the country and to plan their collective responses to fugitive arrests in the city. Smith Court residents sheltered numerous freedom seekers in their homes. Smith Court also served as the battleground in one of the lesser known yet most brazen attacks on a slave catcher in Boston’s history.

African Meeting House as Sanctuary

As of one the five Black churches in Boston, the African Meeting House provided a place to worship and engage with the local community for those who escaped from slavery. Moses Roper, for example, fled slavery in Florida on a vessel bound for New York. In New York, he wrote, “I thought I was free; but I learned I was not and could be taken there” and made his way further north to Boston.[3] He soon discovered that the threat of recapture still existed in Boston, where even the churches could not provide complete sanctuary. According to the Museum of African American History, which now owns and operates the African Meeting House:

The church was not immune to trespass and invasion by Southern slave traders who were hired to find or kidnap people suspected of being self-emancipated. They infiltrated church services and their very presence amounted to harassment since many members were active leaders in the Underground Railroad.[4]

Not only did Roper and others that escaped slavery worship at the African Meeting House, one of them, John Sella Martin, became its minister in 1859.

In addition to its role as a religious center, where free and fugitive alike worshiped together, the African Meeting House provided an important gathering space for groups dedicated to assisting those escaping on the Underground Railroad. For example, the New England Freedom Association held many of their meetings at the African Meeting House. William Cooper Nell, one of the group’s founders, wrote about its September 1845 meeting there:

The object of our Association is to extend a helping hand to all who may bid adieu to whips and chains, and by the welcome light of the North Star, reach a haven where they can be protected from the grasp of the man-stealer…

He further explained the Association’s mission:

to succor those who claim property in themselves, and thereby acknowledge an independence of slavery. Fugitives are constantly presenting themselves for assistance which we are at times unable to afford, in consequence of the lack of means. Donations of money or clothing, information of places where they may remain for a temporary or permanent season as the case may demand, are the instrumentalities by which we aim to effect our object. We feel it to be a legitimate branch of anti-slavery duty, and solicit, therefore, in the name of the panting fugitive, the countenance and support of all who ‘remember those in bonds as bound with them.[5]

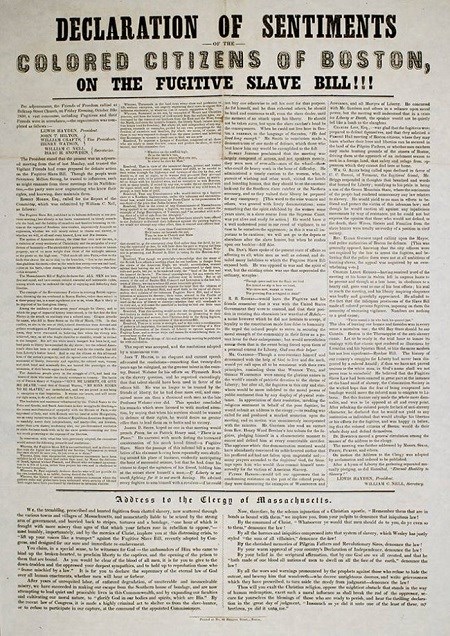

Courtesy of the Boston Athenaeum, 1850

Boston Confronts the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

In 1850, the federal government enacted a new and harsher Fugitive Slave Law to stem the tide of enslaved people escaping on the Underground Railroad. This new law allowed slave owners to send federal marshals to free states in search of runaways. The law also mandated the assistance of state and local authorities and demanded compliance of the public at large. It imposed stiff fines and prison sentences to anyone who assisted fugitives from slavery. Soon after the enactment of this law, the Black community of Boston rallied at the African Meeting House to set forth their collective response.

On October 5, 1850, the Friends of Freedom met in the packed African Meeting House. Organizers included William Nell as well as Lewis Hayden, Boston’s most prominent Underground Railroad leader. The Friends of Freedom promised a sustained fight against the federal government and militant resistance to the Fugitive Slave Law. They called for a League of Freedom “composed of all those who are ready to resist this law, rescue and protect the slave, at every hazard.”[6] William Nell, a historian as well as an activist, reminded the audience of Boston’s proud tradition of resistance in the American Revolution and the leading roles that African Americans, such as Crispus Attucks, played in that struggle. He urged his listeners to follow in the footsteps of these leaders. In his book, More Than Freedom, historian Stephen Kantrowitz discusses this meeting and the ensuing militant activism of Boston’s Black community that followed in its wake:

After 1850, therefore, black Bostonians added a potent new dimension to their assertion of citizenship: concerted physical resistance. In secret meetings, paramilitary mobilization, and street warfare, they openly rebelled against the federal government and its laws. They physically resisted the enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Law, in raids that defied city, state, and federal authorities…In a sense, their final battle against American slavery began in the Belknap Street Church, where William Cooper Nell reminded them of the legacy of Crispus Attucks and urged them to defend their freedom by any means necessary.[7]

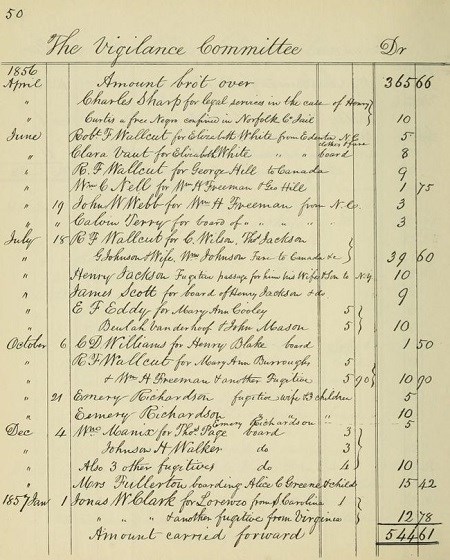

Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston, Dr. Irving H. Bartlett collection, 1830-1880, Cape Cod Community College Archives.

The Safe House at 3 Smith Court

Directly across from the African Meeting House sits 3 Smith Court. Similar to the African Meeting House, this residence has strong ties to the Underground Railroad. James Scott, a Virginia-born clothing dealer and activist, rented part of this house from 1839 to 1865 before buying it outright. Local authorities arrested Scott in February 1851, accusing him of leading the attack on the courthouse that freed Shadrach Minkins, the first person caught under the new fugitive slave law in Boston. While Minkins soon escaped the city for Canada, Scott stood trial for his suspected role in the successful courthouse raid. The jury, however, did not convict him. Whether or not Scott participated in Minkin’s rescue is unknown. Despite being a suspect in this high-profile case, Scott still involved himself in illegal Underground Railroad activity. According to the Account Book of Francis Jackson, Treasurer The Vigilance Committee of Boston, Scott harbored several people in his home at Smith Court, including the fugitives Henry Jackson and his wife and child in July 1856 as well as William West and Robert LeRoy in February 1860.[8]

Between 1850 and 1857, Scott shared his home with William Cooper Nell, one of the most active Underground Railroad operatives in the city. In addition to co-founding the New England Freedom Association in the 1840s, Nell helped form the Boston Vigilance Committee following the enactment of the Fugitive Slave Law. Both of these organizations dedicated themselves to the protection of those escaping slavery. According to the Account Book, the Boston Vigilance Committee reimbursed Nell on “nineteen separate occasions for a range of services to thirty-three named escaped slaves and an unspecified number of unnamed ‘fugitives,’” some of whom boarded at his home on Smith Court.[9]

"The Fiery Eyes of Mrs. Prince"

One of Boston’s most dramatic Underground Railroad confrontations took place on Smith Court in 1847. Local resident Thomas B. Hilton recalled the events of that day in an 1894 newspaper article. He said that a slaveholder named Woodfork came to Boston. According to Hilton:

no name was more familiar and no name more dreaded by those residents who had escaped from southern bondage than this inhuman cowardly kidnapper. Many a poor fugitive had been tracked by him and sent back to his so-called master.

Word spread quickly through the community of Woodfork’s presence. Hilton said, “This information which our people in those times were so accustomed to hear, was enough to keep their eyes and ears on the alert.” Just before noon that day, he continued:

there was a ripple of excitement in the rear of Smith's Court off Belknap Street. It seemed that some children had come out of the court and reported that a slave holder was in Mrs. Dorsey's, a woman who, by some means, had succeeded in shaking off oppressions yoke and reaching Boston. This news, which was always enough to make our people drop everything and go to the rescue, was verified in this instance.

It being working hours scarcely a colored man was seen in the vicinity; but, as it proved, there were those around that showed themselves equal to the occasion. Among these was Mrs. Nancy Prince…, a colored woman of prominence in Boston who, with several others…hurried to the scene…and they all started with the determination to thwart him at all hazards…

Only for an instant did the fiery eyes of Mrs. Prince rest upon the form of the villian…for the next moment she had grappled with him, and before he could fully realize his position she, with the assistance of the colored women that had accompanied her, had dragged him to the door, and thrust him out of the house. By this time quite a number, mostly women and children had gathered near by…whom Mrs. Prince commanded to come to the rescue, telling them to "pelt him with stones and any thing you can get a hold of," which order they proceeded to obey with alacrity. And the slave holder…convinced that he had lost the opportunity of securing his victim, started to retreat, and with his assailants close upon him ran out of the court into Belknap Street.

Only once did the man turn in his head-long flight when, seeing them streaming after him terribly in earnest, their numbers constantly increasing and hearing in his ears their exultant cries and shouts of derision he redoubled his speed and, turning the corner into Cambridge street was soon lost to view.[10]

Though not as well-known or publicized as later cases, such as the rescue of Shadrach Minkins, the actions of Nancy Prince and the women and children that fought alongside her that day are testament to the collective power, resilience, and militant spirit of Boston’s Underground Railroad network, so much of which ties directly to the tucked-away little neighborhood of Smith Court.

Footnotes:

[1] Moses Roper, Narrative of My Escape from Slavery, 1837, (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2003) 40.

[2] Eric Foner, Gateway to Freedom: The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2015), 15.

[3] Foner, Gateway to Freedom, 50.

[4] "The African Meeting House: A Gathering Place for Freedom," The Museum of African American History (Boston, MA).

[5] William Cooper Nell, “Meeting of the New England Freedom Association” in William Cooper Nell: Selected Writings 1832-1874, Edited by Dorothy Porter Wesley and Constance Porter Uzelac (Baltimore: Black Classic Press, 2002) 146-147. Also found in slightly different format in The Liberator, December 12, 1845.

[6] Declaration of Sentiments of the Colored Citizens of Boston, on the Fugitive Slave Bill!!! Broadside. c. October 5, 1850.

[7] Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889 (New York: Penguin Press, 2012) 179-180.

[8] Kathryn Grover and Janine V. Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site," Boston African American National Historic Site, (2002), 58.

[9] Grover and Da Silva, "Historic Resource Study," 59.

[10] "Reminiscences," The Woman's Era 1, no. 5 (August 1894).