Last updated: October 26, 2021

Article

A Brief History Of Tourism In Skagway

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, Inv. # 00631-K. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

An Early History

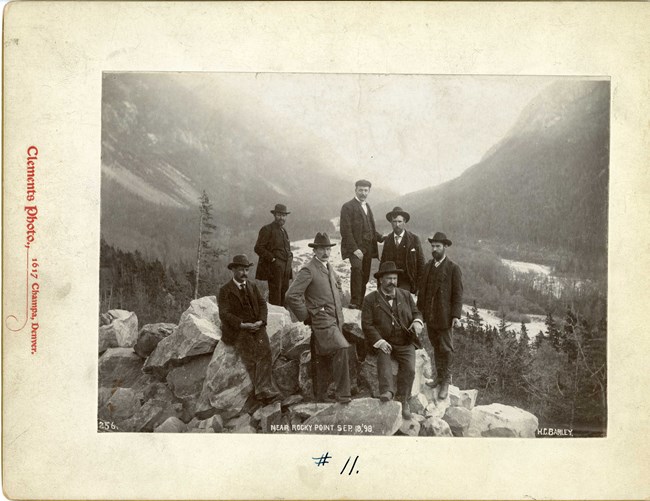

Tourism in southeastern Alaska dates back to the 1880s with cruises up the Inside Passage to see totem poles, the Treadwell Mines in Douglas, and Glacier Bay. By the time of the Klondike Gold Rush tourism was a well-established business in the region. The first documented tourists to come to Skagway were mentioned in the Daily Alaskan newspaper of July 25, 1898 just about a year after the town's founding. The headlines for this story read:

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park,Whiting Collection, KLGO 0004.008.001.001.0011.

And how those excursionists did enjoy themselves. They never expected to see so large a city. Sitka and Juneau were much older, so they expected to find here tents and log cabins and temporary business buildings, they said. And the ladies were met here by friends as refined and well dressed as themselves, which was another surprise. Yes, they had heard of the railroad, some of the gentlemen said, but they thought of it but as another scheme gotten up to catch the unwary. … But they were invited to take a free excursion in the direction of the Klondike on the railroad, and the Yukoners in town and who had braved all the hardships of the interior and returned rosy and hearty and burdened with gold, were invited to accompany them. The ride on the new railroad was one thing; to meet and talk to these brave men of whom they had read so much was another and perhaps a keener enjoyment.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, Whiting Collection, KLGO 0004.008.001.002.0004.

An Upgrade To Tourism

By 1900 Skagway was ready to organize the first annual city wide cleanup day to help beautify the city for the coming tourist season. The Daily Alaskan of May 12th reported that:"Mayor Hislop says there will be a meeting of the city council on Monday evening, and that then steps will be taken to have a systematic cleaning up of the streets and alleys of the city before the advent of the summer tourists."

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 59784. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 55922. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

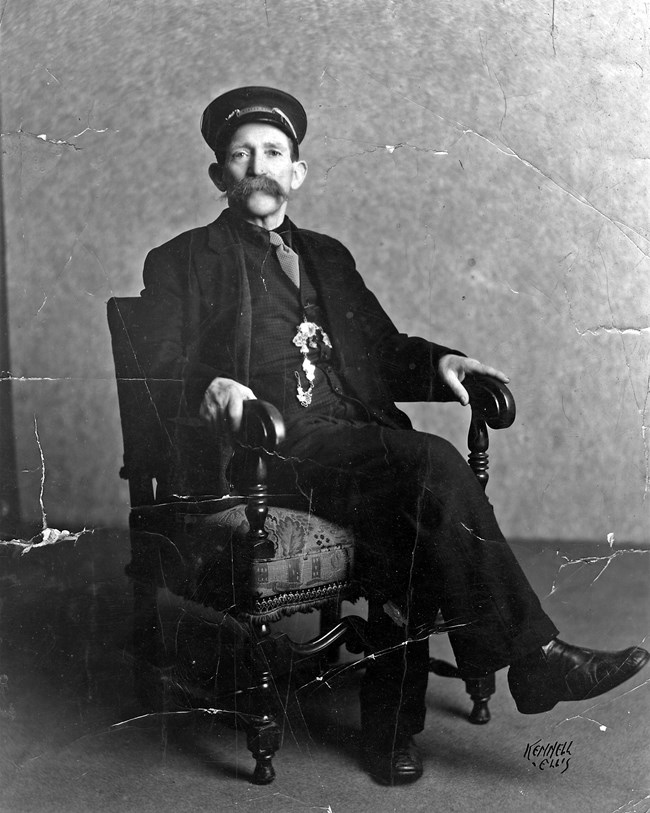

Martin Itjen Tells The Story

The Ship's Register by Moore's Wharf began to be developed in the teens, perhaps earlier, and the White Pass & Yukon Route took advantage of the newfangled motion picture travelogues to promote tourism at the same time. After a brief period of decline during the Great Depression, tourism in Skagway picked up again in the latter half of the 1930s. This was undoubtedly due in large part to Martin Itjen's famed trip to Hollywood in 1935. Martin Itjen arrived in Alaska in 1898, and after two attempts at stampeding in British Columbia he returned to Skagway to settle down. He served as the town's undertaker, wood cutter, coal deliverer, and first and so far only Ford Motor Car dealer and became the premier figure in the town's growing tourist industry. Possibly in the early teens he acquired a Veeracmotor coach (Veerac trucks were built from 1910 to 1914 in Anoka, Minnesota). By the 1920s he had developed a tour of gold rush Skagway and built a "street car" to carry tourists around. This street car was built on a 1908 Packard chassis but the Veerac coach body appears to be part of it.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 55776. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 557722. Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

Rapuzzi Continues Tradition

During the World War II travel to Alaska was restricted by the government for security reasons, which brought tourism to a screeching halt. However, the war did bring soldiers who spent their pay in town and were curious about the town's history. After the war Skagway residents again turned to tourism to help boost the town's economy. By the late 1940s, more tourists than ever before were visiting Alaska, a change Skagway residents welcomed and encouraged through town beautification projects and restoration efforts.Starting in the 1930s, there had been notions to create a National Park in Skagway. Officials in Washington turned down the idea because Skagway was too close to Glacier Bay National Monument. By the 1950s residents began to once again actively embrace the idea. They understood that a National Park would attract more tourists that the town depended on for its economic survival. The National Park Service also began to be interested in the idea. A step in this direction was achieved on June 13, 1962, when the town and the surrounding area became a National Historic Landmark.

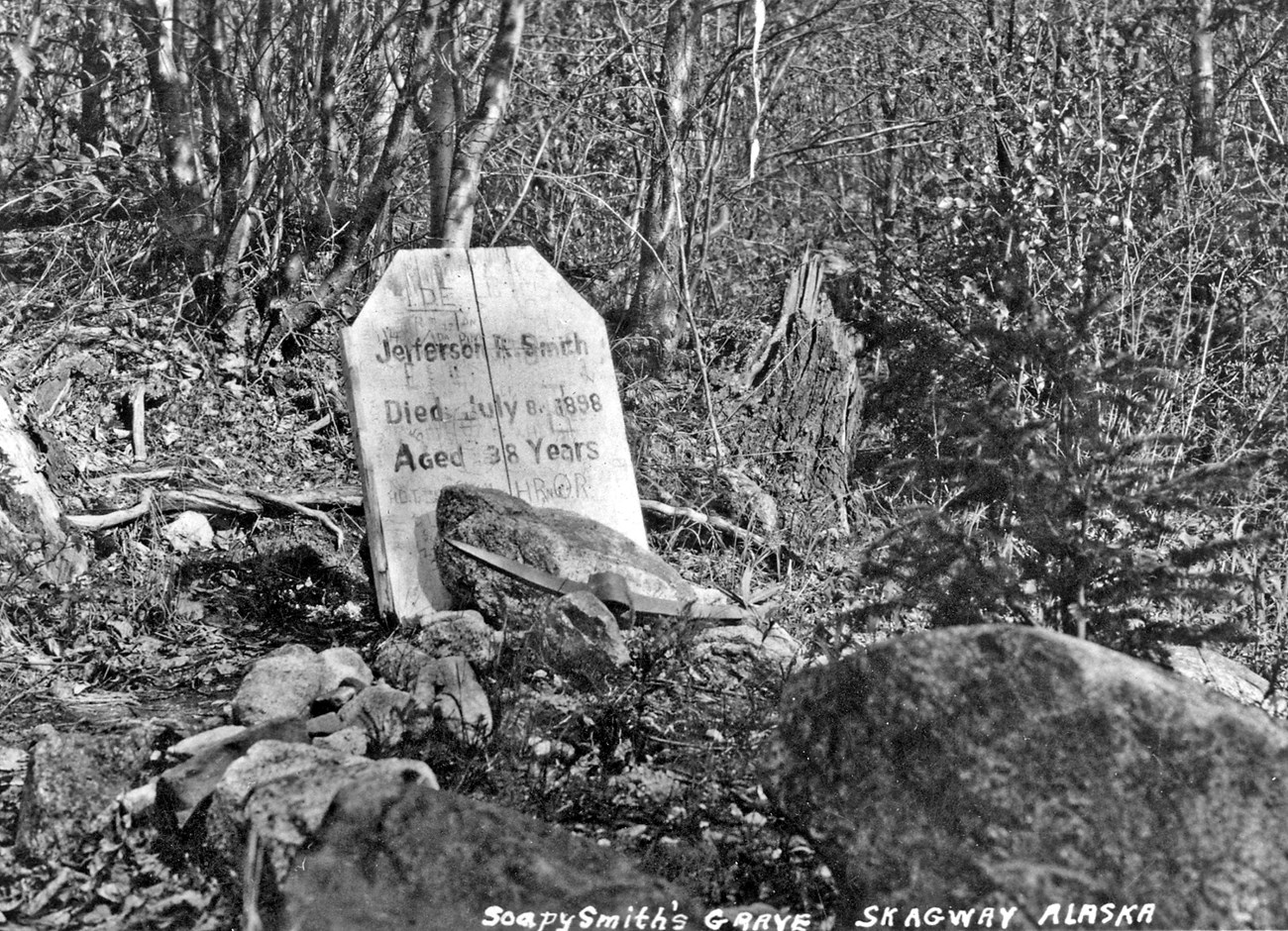

It was during this era of new found enthusiasm for tourism promotion that George Rapuzzi reopened Martin Itjen's Jefferson Smith's Parlor Museum, for the most part closed since Itjen's death in 1942. George was born in Skagway, Alaska, in 1899. A friend of Martin's, he continued in Itjen's footsteps as a tourism promoter and collector of gold rush memorabilia. Rapuzzi acquired Soapy's Parlor following Itjen's death. He moved the parlor museum to Second Avenue in 1963 to be closer to the docks and the tourists, remodeled it once again and by 1967 reopened the parlor museum and ran it as a tourist attraction for another 10-15 years before he died in 1986.

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, George and Edna Rapuzzi Collection, KLGO 55784 . Gift of the Rasmuson Foundation.

NPS/R. Harrison

The National Park Service

In 1972, Skagway became the first city in Alaska to establish a Historic District by city ordnance and the following year the city created the Historic District Commission with an eye to preserving the historic character of the town. In 1976, after numerous studies and reports, President Gerald Ford signed a bill authorizing the creation of Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park. The National Park Service then began the job of hiring staff and purchasing historic buildings in Skagway's Historic District. After that the NPS began the long process of conducting historical research, developing building condition assessments, stabilizing, and then eventually restoring the old buildings it had acquired to their gold rush era splendor. The NPS also sent archeologists underneath buildings in Skagway, over to Dyea, up the Chilkoot Trail and over to the White Pass Unit to document the precious artifacts and features found there.All this hard work by people in the private and public sectors has really paid off for Skagway's economy. In 1982 just over 49,000 people visited Skagway during the summer. The visitor count in 2012 was 866,132 a far cry from those 60 pioneering tourists from Boston that arrived one Skagway morning on July 25, 1898.

Toursim has transformed drastically over the last century in Skagway. The municipality recieves over one million visitors each summer, and Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park offers a variety of walking tours and historic sites for visitors to enjoy!