Last updated: October 26, 2021

Article

Gold Rush Bicycles

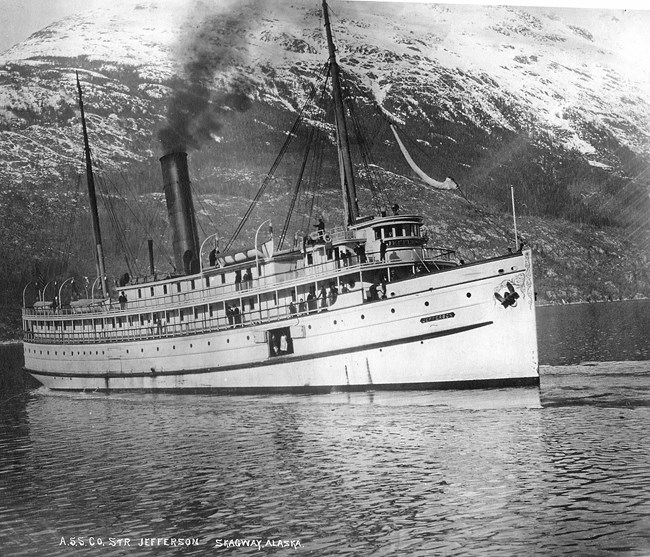

National Park Service, Klondike Gold Rush National Historical Park, NPS-KLGO Candy Waugaman's Collection, KLGO Library TS-206-8919

Gold Is Discovered

As soon as the steamers Excelsior and Portland arrived at their respective docks in San Francisco and Seattle in mid July 1897, huge numbers of people became desperate for any and all means to get to the Yukon goldfields. You could make a fortune without leaving the waterfront by selling steamer tickets at ludicrous prices. Dogs quickly disappeared from city streets all along the West Coast. Thousands of horses and other pack animals would die on the rugged trails to the Yukon interior during the following year and men would die with them, dreaming of the gold most would never reach.

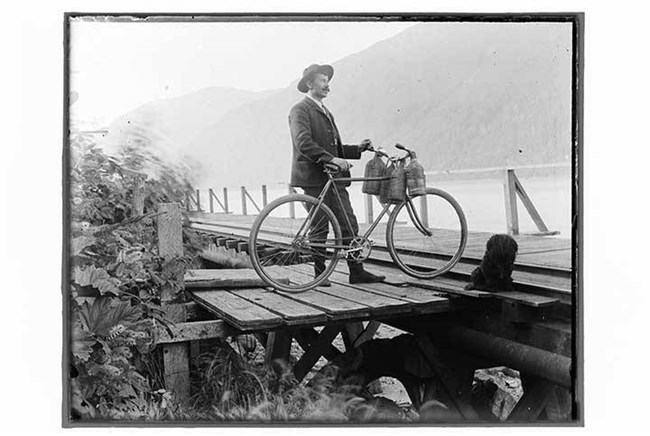

Alaska State Library-Historical Collections, Fhoki Kayamori, Photographs, ca. 1912-1941. ASL-PCA-55. ASL-P55-293

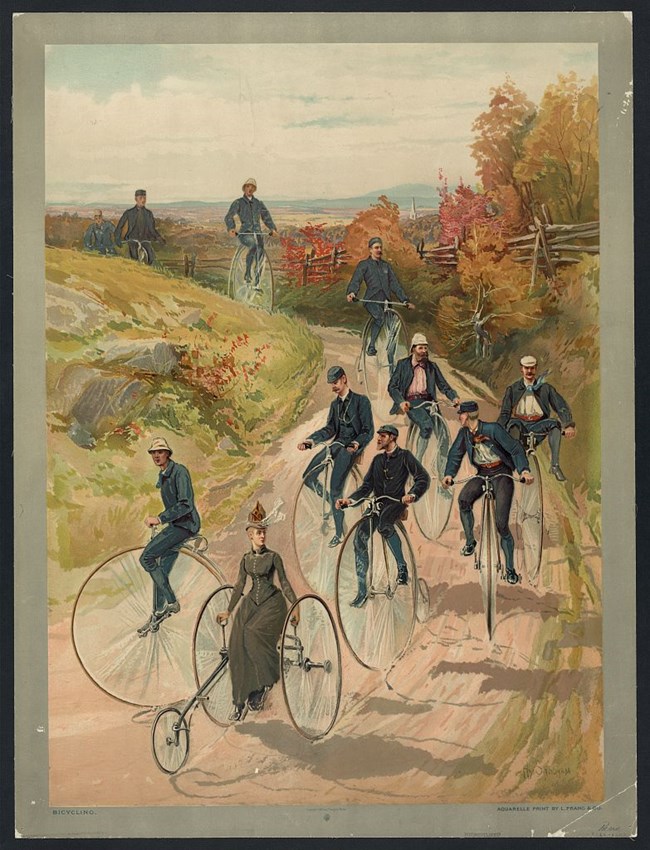

Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-25339

The Race Is On

Some bicycle owners heading north used their “iron steeds” to carry goods rather than themselves. Early on, two bicycles arrived in Skagway, where the pedals were removed and racks and frames were added so that the bikes could carry two-hundred-pound loads. Of course, no one could simply bike over the White Pass Trail – the North West Mounted Police required everyone to carry with them a year’s supply of food, which when added to the tent, stove, clothing, and other supplies, translated into nearly a ton of goods or more. This load could never have fitted on a bicycle, even if the rider could have ridden it over the pass in the first place. Bicycles of the time were not light machines, either, making one an unnecessary burden for the already overworked Klondiker.

Library of Congress, LC-DIG-pga-04039

Bicycle travel became far more reasonable after roadhouses were established at every twenty miles along the trail. No longer were riders required to carry their provisions and shelter with them and they could travel light. There were still few roads in the Yukon, however, as river travel was considered preferable in summer, which meant that cyclists were hard-pressed to find a passable trail from Skagway to Dawson City until the rivers froze with the coming of the winter months.

The Journey By Wheel

There is some merit to the use of bicycles on the trail, in theory at least: cyclists could follow the tracks in the snow left by dogsleds with relative ease; bicycles were faster than either dog teams or horses; and you did not have to feed a bike. You did, however, have to deal with flat tires, frozen bearings, eyestrain and snow blindness, and face the risks that came with riding at high speeds over icy ground. Terry, the man who may have made the first successful bicycle trip to Dawson, managed to “patch” a flat tire by pouring water into the puncture hole and allowing it to freeze. Edward Jesson wrote an account of his ride down the Yukon after the height of the rush had passed. He attempted to ride in temperatures of 48-below zero, and said of the experience:

The rubber tires on my wheel were frozen hard and stiff as gas pipe. The oil in the bearing was frozen and I could scarcely ride it. My nose was freezing and I had to hold the handlebars with both hands, not being able to ride yet with one hand and rub my nose with the other.

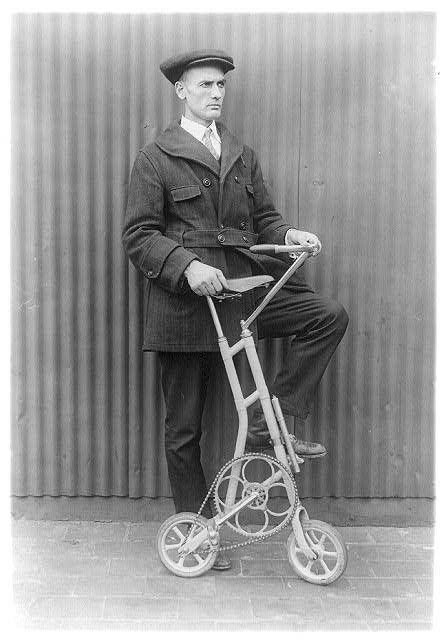

Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsc-01569

The trail started on a long slope from the base of the mountain, across its face, ever-ascending toward the narrow pass near the summit through which all traffic had to go. I have no idea of the geographical length of that trail, but it seemed not less than a thousand miles. The terrific gales had blown the snow over the summit and lodged it on the breast of the mountain, where it was piled up from twenty to a hundred feet in depth. Constant traffic had beaten down the snow until the trail itself was firm enough, but when you got off the trail into the loose snow it was like falling into an ocean of feathers. To make travel more interesting, a blizzard welcomed us as we started up the trail.

The steepness of the trail, and the freshly fallen and wind-blown snow made it impossible to attempt to ride the bicycles, so all we could do was take them on our backs and start up in the face of the gale. . . . A man with a bicycle on his back is not only classed as a pedestrian, but as a fool.

Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-33911

The Rush of Bicycles

Earlier that month, the same paper published an article about the return of a party of six who had gone out to Five Fingers by bicycle. The group told the paper that the snowy trail, while very narrow, was perfectly adequate for bicycles, pedestrians, and narrow sleds, and that they had travelled 101 miles on their best day. Miles of trails around Dawson and through the Yukon were fine for cycling, but others were hard and dangerous. In addition to his description of the summit climb, John Clark also wrote about what it was like to cycle on a frozen river at thirty below zero with high winds blowing:

It was blowing about sixty miles per hour, and all we could do was to put on the brakes and hold the bicycle straight and trust to luck, and even then we must have travelled at times the rate of fully thirty miles per hour . . . when we struck a sideling place, down we went, and unless we held onto the wheel in falling, the wind would whirl it down river on the glare ice, even though it was on its side. . . To vary the monotony of falling on glare ice, we frequently ran into overflow on top of the ice. This was water that had not frozen during the night or ice that would not hold us up, and when we struck the water we went down again. We would have to pick up our wheels and carry them on our backs and splash through, until propelled up the wind we found clear ice. Then we would have to kick the ice off the chains and other parts of the wheel to enable us to go on, as the water froze the moment we picked up the wheels.

Jesson also encountered dangerous sections when he rode down the Yukon River in 1900:

[The wind] grew stronger and drifted the trail full and some places the ice was slick and clean. I was back peddling to keep from going too fast and at times the wind picked me up and landed me where it pleased, into a snow bank or an ice jam upside down . . . a gust caught me on a smooth stretch here and whirled me into a rough patch of ice almost busting my knee, skinning my hands and elbows and broke one of my handlebars. The wind pulled us out of the rough ice and was kiting us down over the glare ice at good speed. I began to grab the differed pieces of the handlebar and stick them in by pickets all around. At last we landed in another ice jam and hung up. I was quite a while rubbing my left knee so I could use it and by pushing the wheel along and leaning on it, I found that I could hobble along on it.

We should note that Jesson’s bike had no derailleur, no variable gears, no freewheel and no brakes; to slow down, he would have had to backpedal. His extremely simple bicycle was not un-common; few bicycles had any kind of special features for the harsh climate. Some northern cyclists used special tires designed for the ice, but the majority was riding the same wheels that their relatives down south had. Clark, riding several years later, was better equipped as he had a bike with a coaster brake.

As the rush went on, Seattle papers regularly reported sales of bicycles to stampeders on their way to Dawson. In March 1900, The Argus wrote:

It is not generally known, perhaps that the Klondike trade, which has done so much for Seattle, extends to the bicycle business. Local dealers report that the success of cyclists on the trail has caused this branch of their trade to change from a mere experiment to a steady growing demand. No less than a dozen wheels have been sold by dealers in this city for Dawson in the past two weeks. It is said that in March the trail is in such condition as to make travelling by wheel practical. Scarcely a steamer sails for the North that does not carry bicycles. The Dawson Bicycle Club will doubtless be heard from soon.

Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-25340