Part of a series of articles titled Democracy Limited: The Suffrage "Prison Special" Tour of 1919.

Article

Democracy Limited: Introduction

“If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.” —Abigail Adams, 1776

The Telling All Americans’ Stories (TAAS) Democracy Limited is an article series exploring the impact of the National Woman’s Party’s 1919 “Prison Special” Tour. In the early spring of 1919, 26 women boarded a train leaving Union Station in Washington, D.C. and heading south. Their goal: to share the story of the horror they endured in prison. They had been arrested for fighting for women’s right to vote. This article series explores how and why the “Prison Special” aided the cause of women’s suffrage and how it helped secure the ratification of the 19th Amendment the following year.

These women and their prison stays were notable because of their standing in society. They were white, educated, and well-connected. In a society with deeply ingrained racial and class prejudice, women of their stature were expected to stay home to care for their families. Men occupied the more active “public sphere” of business, trade, and politics. As wives and mothers, women occupied the “domestic sphere”—cooking, cleaning, and taking care of the home and children. They were not expected to work outside the home. They were excluded from politics. And they certainly did not go to prison.

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/images/vc006195.jpg).

Except when they did. By 1919, several hundred women had been arrested for picketing the White House and protesting for the right to vote. Women of all ages, races, and socioeconomic classes were prohibited from voting. While there were Western states that did allow women to vote, in most states women were banned from voting. In the few states where women could vote, in most cases they were limited to local and state elections. The fight for women’s right to vote, which had started generations earlier, is known as the women’s suffrage movement.

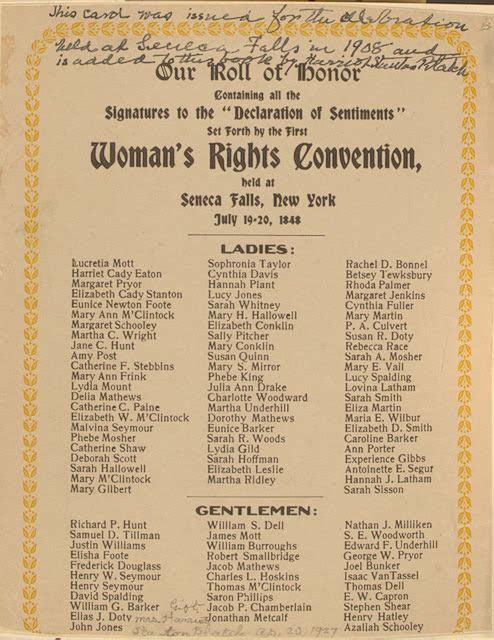

The women’s suffrage movement had many starting points, though the most well-known is the 1848 convention in Seneca Falls, New York. The Women’s Rights National Historical Park in New York explores the grassroots organization that resulted in the first Women’s Rights Convention. The Declaration of Sentiments outlined the rights women had been denied by the United States government and the goal of suffrage activists for the next 72 years: “immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to [women] as citizens of these United States.”

Thirty years after that historic convention, the Anthony Amendment was first proposed to Congress. Named for women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony, it was meant as an addition to the 15th Amendment. The 15th Amendment states that neither state nor federal governments can prohibit a citizen’s right to vote based on their “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” The Anthony Amendment proposed to add “...on account of their sex,” to ensure women, too, would be granted their full rights as citizens. Suffrage in America: The 15th and 19th Amendments discusses the relationship between these laws and their role in securing civil rights for all Americans. Over the next few decades, Congress repeatedly rejected the amendment.

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/2016679928).

The “what” of the suffrage movement was clear, but the “how” was a little more difficult. Women and leaders within the movement disagreed on the best way to achieve their goal. The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), the largest women’s suffrage organization, favored a state-by-state approach. Their goal was to change state constitutions one by one. The National Woman’s Party (NWP) formed later as a response to the slowness of NAWSA’s state approach. Under the leadership of Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, the NWP focused its attention on amending the U.S. Constitution.

From the collections of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/mnwp000192).

During the first decade of the 1900s, little changed for women politically. Alice Paul’s new leadership reignited the movement through a series of actions intended to attract attention to the cause. Through shock and outrage, Paul sought to stir up complacent Americans. According to Paul, only then would they see the injustice in the denial of women’s rights as citizens. The Prison Special tour did exactly this.

Bibliography

"A History of Suffrage," Turning Point Suffragist Memorial. https://suffragistmemorial.org/a-history-of-suffrage.

"Detailed Chronology - National Woman's Party History." Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party. Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/static/collections/women-of-protest/images/detchron.pdf.

Stevens, Doris. Jailed for Freedom. New York: Boni & Liveright, 1920.

by Brianna Nuñez-Franklin

Last updated: August 4, 2020