Last updated: August 18, 2017

Article

Connecticut Abolitionists

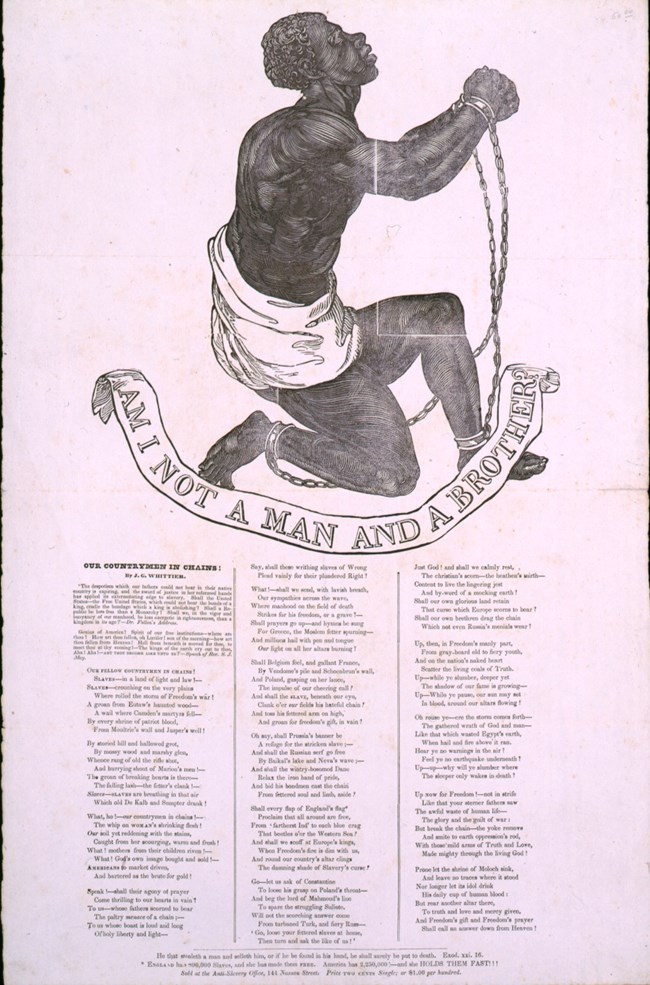

Setting Context: the National Abolition Movement

William Lloyd Garrison, with others formed the American Anti-Slavery Society (the Society) in 1833. It advocated for the abolition of slavery within the United States. Notable members frequent speakers included former slaves Frederick Douglass and William Wells Brown.

In 1840 the Society split. One faction, led by Garrison, advocated for the dissolution of the Federal government. It believed that the Constitution was a flawed document that supported slavery, and the only option was to create a new nation. It was suspicious of religion, and supported having women in leadership roles. Garrison’s opponents thought he was too radical. Opponents formed two new organizations - the Liberty Party and the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society.

Founders of the Liberty Party advocated for political involvement. They believed that electing abolitionists to office could end slavery. The party put forth one Presidential candidate, James Birney, in both 1840 and 1844. He was unsuccessful in both races.

The American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (AFASS) promoted religion in abolitionism. They thought that religious teachings, not political activism, would create a moral epiphany. AFASS didn’t give women the right to vote in proceedings or hold positions.

Black abolitionists were often kept on the margins of the movement they had sustained and promoted. Increasingly, free blacks had their own meetings and read African American newspapers. These included Samuel Cornish's Colored American and Frederick Douglass's abolitionist weekly North Star.

Connecticut: A History of Slavery and Abolitionism

Slavery in Connecticut dated back to the mid-1600s. By the American Revolution, Connecticut had more enslaved Africans than any other state in New England. In 1784 it passed an act of Gradual Abolition. It stated that those children born into slavery after March 1, 1784 would be freed by the time they turned 25. As a result, slavery in Connecticut was practiced until 1848.

In 1833, Prudence Crandall opened a school for "young misses of color" in Canterbury, Connecticut. The townspeople protested and harassed Crandall and her students. She resisted and kept her school open. In 1834, Connecticut's General Assembly passed what came to be known as the Black Law. The Black Law restricted African Americans from coming into Connecticut to get an education and prohibited anyone from opening a school to educate African Americans from outside the state without getting a town's permission. This law, in effect, expelled those attending Crandall's school and closed it down. The Prudence Crandall trial and the establishment of the Connecticut Black Law of 1834 were huge setbacks for the abolitionist movement in the state.

The Connecticut Anti-Slavery Society was founded in 1838. By 1839, Connecticut abolitionism found itself at a crossroads. After several disheartening legal defeats like the Crandall case, Connecticut abolitionists were in search of a new cause to bring slavery to the public's eye. Abolitionists embraced the publicity given to the Amistad captives' plight as a means to publicize and reinvigorate their cause.

Abolitionists Lewis Tappan, Joshua Leavitt (both from New York) and Simeon Jocelyn (from Connecticut) formed the Amistad Committee to defend the Amistad captives. The Amistad Committee appealed to the public for both legal and living expenses throughout the trial. Jocelyn, founding member of New Haven's Third Church, was a white abolitionist and the first pastor of New Haven's Congregational church for African Americans in the 1820s. In 1831, he proposed the establishment in New Haven of the first institution of higher education serving African Americans--never realized because of overwhelming opposition.

Jocelyn was supported by New Haven attorney Roger Sherman Baldwin. Baldwin, a member of North Church, offered his legal services to the Amistad captives. For two years, Baldwin successfully defended the Africans' right to freedom (first assisted by some fellow Yale graduates, later by former President John Quincy Adams). As abolitionists, Baldwin and Adams seized the opportunity to refocus the case on human rights and to challenge the institution of slavery on moral and constitutional grounds. Baldwin and Jocelyn were also instrumental in securing first local, then national support for the captives.

Lewis Tappan, another member of the Amistad Committee, corresponded with his friend Austin F. Williams during the Mende's imprisonment. Williams and fellow Farmington abolitionists Samuel Deming, Horace Cowles and John Treadwell Norton were founding members and officers of the Connecticut Anti-Slavery Society, and had established possibly the first local anti-slavery society in the state. They arranged for the Africans to be sheltered in Farmington after their release while the Amistad Committee raised funds to send them home to Sierra Leone.

Oral tradition indicates that Williams was an Underground Railroad conductor and, along with other citizens, made the Farmington community a major Underground Railroad stop. After the Civil War, Williams was appointed director of the Freedman's Bureau of New England and New York and found housing and job opportunities for freed African Americans. Deming was a legislator, merchant, farmer and one of the town's most respected citizens and churchmen. Cowles had been an early advocate for abolition. Norton was an active international abolitionist and while in Farmington, the Mende were frequent guests at his home, performing gymnastics on his lawn. His son, John Pitkin Norton, then a Yale student and later a much-honored professor, served as a tutor for the Africans and detailed his conversations with them in his diaries.

While in Farmington, the Amistad Committee required that the Mende attend the First Congregational Church. They attended school five hours each morning at Deming's store. The Mende also were taken to different parts of New England and asked to participate in various fundraising events. With the money raised at these events, the Amistad Committee hoped to establish a Christian missionary in Africa and pay for the Mende's transportation home. Within a few months, it became clear that the Mende were anxious to return home. The Mende, accompanied by several missionaries (two of whom were black), left Farmington on November 27, 1841, and arrived in Sierra Leone in January 1842.

National coverage of the Africans' case before the U.S. Supreme Court gave fresh impetus to the cause of abolishing slavery. One of the first "civil rights" cases in the history of the United States, the Amistad trial illuminated tensions concerning the issue of slavery. For the next 20 years, the abolitionist movement would find the momentum necessary to propel this issue forward, ending with an explosive national conflict: the American Civil War.

This is just one story associated with the Amistad event. To learn more, please visit the main Stories page of this travel itinerary.

Sources:

The above essay includes passages from Exploring a Common Past: Researching and Interpreting the Underground Railroad. For further information on Connecticut Abolitionists, you may also want to visit www.yaleslavery.org

https://connecticuthistory.org/topics-page/slavery-and-abolition/

http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/w/American_Anti-Slavery_Society

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4p1561.html

http://www.ohiohistorycentral.org/w/Liberty_Party

http://amistadresearchcenter.tulane.edu/archon/?p=creators/creator&id=26