Just two weeks before he was killed in battle, Tecumseh delivered a rousing speech.

"Our lives are in the hands of the Great Spirit. We are determined to defend our lands, and if it is his will, we wish to leave our bones upon them.” Tecumseh, Fort Malden, September 18, 1813

Weltmuseum Wien

The decision for a tribal warrior to strike out on the war path was a decision that rested entirely with the individual. It was an exercise in complete freedom of the warrior. He had no obligation to fight. Many warriors confronted a choice with whom to side during War of 1812: the Americans or British, depending on which power best served their interests. Warriors attended councils, listening to powerful orators such as Tecumseh, Main Poc, Roundhead and Assiginack. Once the warrior chose if and who he would fight, traditional and ceremonial protocols followed.

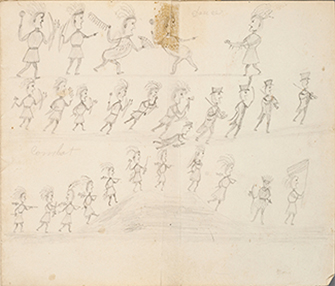

In the days leading up to the attack on Fort Detroit in 1812, hundreds of warriors assembled. Odawa, Ojibway, Potawatomi, Shawnee and other warriors danced their war dances and sang their war songs before a large fire. A British soldier who witnessed the warriors’ preparations the night before the attack described the scene as “standing at the gates of hell,” surrounded by warriors fully adorned in war paint and nearly naked.

Warriors would often fast before going into battle. Guardian spirits were called upon during this ceremony. Powerful entities such as thunderbirds, panthers and other spirits would guide warriors. These spirits would be represented on canoes, in war bundles and on war clubs, individualized to each warrior. These items were thought to be infused with a life of their own. Once on the war path, there were more protocols. Ceremonial leaders would be part of the war party, engaging in ceremony to help understand where enemies would be and the best times to attack, among other information. This information would be obtained through dreams, prayer or direct communication with the spirits. Spiritual leaders were often paired with powerful war chiefs throughout history; Pontiac, Black Hawk and Tecumseh are some of the famous chiefs who consulted with such men. Appearance also played a large role in a warrior going to war. The hair was fashioned in a certain manner, either with a scalp lock, mohawk or shaven. Paint representing war was applied, with the colors varying from tribe to tribe. Red paint was a predominant color for war for tribes in the Great Lakes. Traditional tattoos were shown and the dress stripped down to bare essentials.

If a warrior felt the war party would fail, he could leave at any time. No one would stop him, as it was his right as a warrior to come and go as he pleased. Other warriors would join the war party as it travelled to the battle. The war party was very much a living, breathing force.

Men were not just warriors; they were fathers, brothers, husbands, and providers. Going to war put a huge strain on a village, leaving elders, women and children to provide for the community. Young boys had to hunt, trap and fish. Villages would be vulnerable to counterattacks from enemies. The decision to go to war was a complicated one for an indigenous man. If he lost his life on the war path, his family and community would suffer. Each casualty of war resonated throughout the community, and the needs and influences of that community shaped a warrior's decision.

Last updated: August 14, 2017