Way Out West

In the American West, gold and silver miners had long used the high drop of a mountain stream to power their mining operations. As early as 1891, mine owner L. L. Nunn diverted water from a tributary of the San Miguel River to run a stamp mill at his Gold King Mine near Telluride, Colorado. The water dropped 320 feet to turn a waterwheel belted to a 3,000-volt Westinghouse AC generator housed in a rough cabin; the set-up was known as the Ames Powerplant. Once generated, the electricity traveled 2.6 miles uphill, through copper wires, to run a motor used to crush gold ore.

Hydroelectricity proved especially valuable in the mining West because wood, first used to power steam engines, had become scarce as the timber was stripped, and coal had to be packed in over rough terrain, making it expensive. The West’s high mountain streams, with their potential of producing hydroelectricity, also proved valuable to a newcomer in the American West: the U.S. Reclamation Service (today’s Bureau of Reclamation), established in 1902 to construct and operate dams and canal systems to irrigate – and thus encourage settlement – in 16 arid and semi-arid Western States.

Because Congress did not envision the generation of electricity as part of Reclamation’s mission, the Reclamation Act of 1902 did not mention hydroelectric power. In the years ahead, however, as Reclamation began building dams in remote locations, the agency realized – as the West’s miners had long known – that a small, on-site hydroelectric plant had great advantages: It could power the machinery used in building a dam. Though no one could have realized it in 1902, the electrification of the American West would develop hand in hand with the Federal Government’s irrigation projects.

The Power to Build a Dam

The 280-foot-high Theodore Roosevelt Dam, completed by Reclamation in 1911 in a remote canyon on Arizona’s Salt River, proved the advantages of hydroelectricity early-on. So remote was the site of the dam that Reclamation built its own supply line from the railhead at Mesa – a 42-mile-long road carved from an ancient Indian path that came to be known as the Apache Trail. Nearly 400 laborers, Apache among them, were enlisted to finish the last difficult miles. In the meantime, mule teams hauled construction materials over a two-rut wagon road from a railhead at the mining town of Globe.

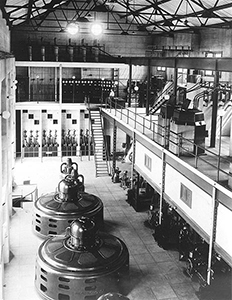

Wrestling with the expense and rough terrain was Arthur Powell Davis, later appointed Director of the Reclamation Service, who proposed an excellent idea: Build a temporary, on-site hydroelectric plant to power the machines that would build Roosevelt Dam. Water power – rather than expensive fuel oil that had to be hauled in – would power the equipment to crush rock, run the saw mill, mix concrete, and lift heavy stone blocks into place. Electricity also could light the construction camp and heat the buildings where workers lived. To that end, Reclamation diverted water from the Salt River into a 19-mile-long power canal and through a penstock to spin a turbine in a temporary AC powerplant, where a 950-kilowatt generator converted the power of water into electricity.

Reclamation also soon recognized that hydroelectricity generated in its powerplants could be used on irrigation projects to operate pumps that prevented saturation of the land or that lifted water to canals on higher terrace lands, which increased the number of acres that could be irrigated. On the Minidoka Project in Idaho, for instance, gravity-flow canals irrigated lands on the north side of the Snake River, but pumping was required to reach land on higher terraces on the south side of the Snake River. In fact, the need to power lift station pumps to irrigate an additional 50,000 acres justified construction of the Minidoka Powerplant. Thus, while irrigation was the sole purpose of these early Reclamation projects, hydroelectric powerplants proved essential not only in building dams, but also in running the irrigation works.

The Sale or Lease of Surplus Power

Although the Reclamation Service did not set out to get into the electricity business, the opportunity soon arose to sell surplus electricity to commercial users. Congress quickly acted to provide legal authority through passage of the Town Sites and Power Development Act of April 16, 1906. The Act authorized the Reclamation Service to sell or lease surplus electrical power, with the proceeds to be applied toward repayment of the construction costs associated with the reclamation project. Congress’ action foreshadowed Reclamation’s future role as a major commercial supplier of electricity in the West, although in these early years powerplants could only be built if needed for irrigation purposes, and they could not be designed to generate significantly more power than was needed for that purpose.

Once Congress signed the Town Sites and Power Development Act, the Reclamation Service quickly arranged for commercial power sale or lease of surplus power on every irrigation project that contained a powerplant. By the 1910s, powerplants on the Minidoka Project and the Salt River Project in Arizona were Reclamation’s largest commercial power producers. At Minidoka as much as 13 percent of the total power generated was surplus and therefore available for sale or lease. Commercial deliveries of electricity to the towns of Burley, Rupert, and Heyburn, Idaho began in 1910. Reclamation built the substations and transmission lines, and the towns or their agents built the distribution circuits and arranged sales to consumers. Reclamation set the rates and also signed contracts to supply electricity to several villages and some manufacturers, including the Amalgamated Sugar Company in Burley.

Because it was cost prohibitive to build power lines to outlying areas of the Minidoka Project, Reclamation was slow to arrange sales to farmers. Instead, Reclamation encouraged groups of farmers to organize cooperative utility companies to build the lines. By 1920, nearly half of the 2,400 farms on Minidoka Project lands had wired their homes and farm buildings for electricity and were enjoying the comfort and convenience of electricity decades before many other rural areas, even those in the East. All told, more than 70 percent of Minidoka Project residents and businesses were heating and lighting their homes and plugging in their electric irons, washing machines, vacuum cleaners and stoves thanks to the surplus electricity from the Minidoka Powerplant.

To advertise the benefits of the power it generated, Reclamation nicknamed Minidoka the “Electric Project” and Rupert the “Electric Town.” However, it wasn’t long before Minidoka was surpassed by the Salt River Project in Arizona. By 1929, the Salt River Project had achieved 100 percent electrification of its 7,000 project farms.

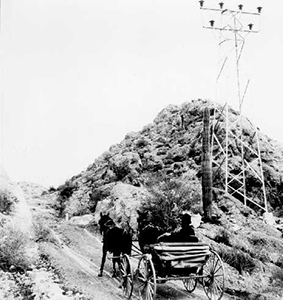

Electricity was first generated on the Salt River Project to construct Roosevelt Dam and was then expanded to operate pumps needed for irrigation and drainage. In 1907, the Secretary of the Interior committed, for 10 years, to sell 1,500 kWs of electricity generated at Roosevelt Dam to the Phoenix-based Pacific Gas and Electric Company (PG&E) and to refrain from providing or retailing power during that time to any other entity in Phoenix. As part of its commitment, Reclamation engineers built transmission lines from the Roosevelt Powerplant to Phoenix, where PG&E took charge of distribution.

The potential profit from the sale of electricity in the Salt River Valley was significant. Therefore, when operation of the Salt River Project was turned over to the Salt River Valley Water Users Association in 1917, the association board decided to build additional dams with powerplants on the Salt River below Roosevelt Dam. The association could use the revenue to repay construction costs and to defray operation and maintenance expenses. Although the Reclamation Service did not build these new dams or powerplants or market their power, the electricity was made possible because of the water stored behind Roosevelt Dam. Electricity generated from water released from Roosevelt Dam soon supplied much of Phoenix’s early power needs, lighting homes and businesses, running streetcars, ice plants, and alfalfa mills, and supplying the electricity that fueled the state’s copper industry.

Power Revenue and Repayment

The Reclamation Act of 1902 mandated that the construction costs of dams, canals, powerplants, and other project facilities be repaid by the water users. Initially, irrigators were required to repay the government’s construction costs within 10 years. It often was the case, however, that water users simply did not have the ability to make their payments because the actual costs of construction, as well as those to establish a new farm, were much higher than expected. A downturn in the agricultural economy did not help.

Construction of Roosevelt Dam, for instance, was initially estimated to cost about $1.9 million, but when the Federal bill for the dam and the Salt River Project irrigation system landed on the desk of the Salt River Valley Water Users’ Association, it topped $10 million, a charge that amounted to $60 per acre for landowners receiving water.

Congress, in 1914, extended the repayment period for Reclamation projects from 10 years to 20 years, and a dozen years later extended it again, to 40 years. But repayments continued to lag. In 1923, a Fact Finder’s Commission reported that Reclamation had spent $135 million on its many projects, but repayments totaled less than $10 million. While irrigation would always remain Reclamation’s primary mission, the sale of electricity proved to be, even in these early years, the “paying partner of irrigation.” As early as the mid-1910s, Reclamation’s power sales surpassed $500,000 a year. As the years progressed, Reclamation and water users would turn more and more to the revenues that could be generated by the sale of hydropower as a way to relieve debt.

A Growing Industry

When Woodrow Wilson entered the White House in 1912, hydropower was the nation’s fastest growing source of electric generation, although it still accounted for only 16 percent of all electricity produced. With the nation’s entry into World War I, the demand for electrical power increased to support manufacturing of materials needed for the war effort. Standardization also increased because utility companies were encouraged, and in some cases ordered, to interconnect with one another so that excess power could be transferred from one war industry service area to another to avoid shortages. Huge new powerplants, both steam and hydroelectric, were built, increasing American generating capacity by 10 percent by the end of the war.

Deciding who should have the right to generate and deliver hydroelectric power has entailed a long-standing and often contentious debate over the proper relationship between private business and government. Private power companies, historian William D. Rowley explains, have long feared competition from “public power” – power created by Federal, state, and local governmental agencies – and mounted enormous campaigns against it, arguing that government enterprises are inefficient and smack of socialism. Private power proponents believed electricity should follow the pattern of laissez-faire economics, but advocates of public power believed that public ownership would keep prices fair and low. Others believed electricity should stay in private hands but be regulated by third parties.

The debate culminated in the Federal Water Power Act of 1920, which established the Federal Power Commission (FPC). The FPC was authorized to issue 50-year permits for hydroelectric dams on the nation’s navigable waters, cementing Federal involvement in the development and regulation of hydropower resources, both private and public.

But even so, as historian David E. Nye writes, the electrification of America, from its inception, was primarily the result of private enterprise. This was, in part, due to the decentralized structure of American government and the relative ease with which private corporations could obtain capital and expand. Like the railroad and steel industries in the early twentieth century, electric utilities, seeking to maximize profits, began to consolidate and, as natural monopolies, charge customers for all the services they provided. These huge holding companies swallowed local service companies and created regional power systems that had more reliability. But small independents, lacking market and capital, often were left without the means to take advantage of big generating facilities and high voltage, long distance transmission. By 1932, three holding companies controlled half of the entire U.S. electric utility industry. Their monopoly led to abuse, such as charging exorbitant service fees and overvaluing purchases. Public distrust came to a head with the stock market crash of 1929. When the 1932 presidential election put Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the White House, public power received a tremendous boost.

The New Deal

Roosevelt’s “New Deal” created new government agencies, such as the Tennessee Valley Authority, and launched numerous public works projects in an effort to “prime the pump” and lift the nation out of the Great Depression. New York City got the Lincoln Tunnel, dug under the Hudson River; Florida got a miles-long causeway linking the Florida Keys to the mainland; and the American West got big new dams and powerplants as the Public Works Administration (PWA), designed to spend “big bucks on big projects,” funneled unprecedented funds to the Bureau of Reclamation, which greatly expanded Reclamation’s mission.

By the outbreak of World War II, the PWA had provided funding for 37 Reclamation projects, including major storage dams with massive powerplants such as Grand Coulee on the Columbia River in Washington State and Shasta in California’s Central Valley. The Colorado - Big Thompson Project boasted the 13.1-mile Alva B. Adams tunnel, which cut under the continental divide –and Rocky Mountain National Park – as it transferred water from the Western Slope of the Rocky Mountains to Colorado’s more populated Front Range. So significant was the decade of the 1930s to the Bureau of Reclamation that it “permitted Reclamation to break free from the past” as it became the “major water resource bureau in the West.”

Legislation enacted during the Roosevelt years also had a tremendous impact on the business of creating and transmitting electricity. Especially significant for the lives of ordinary people was the Rural Electrification Act of 1936, enacted at a time when only 10 percent of rural Americans had electricity. As late as 1940, one-third of rural Americans still hand-pumped water from wells and cooked with wood and coal. Fewer than half had indoor plumbing, and two-thirds had no central heating. Through the Rural Electrification Administration, the Federal Government offered loans to states, public utilities, electrical cooperatives, and municipalities to build power lines to farms and ranches, thereby bringing electricity into rural areas where it had never been.

The 1935 Public Utility Holding Company Act (the Wheeler-Rayburn Act) spelled out rules for utility companies that would shape the electric industry for more than 50 years, while the 1939 Reclamation Project Act would guide the future of the Bureau of Reclamation’s power program. From now on, in planning projects, Reclamation was directed to consider the multiple uses to be achieved: not only irrigation, but public power, municipal water, navigation, and flood control. No longer would Reclamation be limited to generating power only to satisfy the operational demands of a particular project; instead, Reclamation’s hydropower development could go as big as a site supported. Significantly, the two acts came on the heels of one of the greatest engineering feats in American history: the construction of Hoover Dam.

A New Era for Reclamation’s Hydropower Program

Hoover Dam, the centerpiece of Reclamation’s 1928 Boulder Canyon Project, not only heralded a new era in dam building, but a new way of paying for dam construction, which now pivoted on maximizing the capability to generate electricity for commercial sale. So important was recovering construction costs from power generation at Hoover Dam that the Boulder Canyon Project Act required not only the construction of a powerplant, but one “suitable for the fullest economic development of electrical energy.”

Hoover was the first of Reclamation’s dams authorized as “multi-purpose,” while the entire Boulder Canyon Project went far beyond Reclamation’s original single-focus mission to build water works to irrigate the arid West. With its All-American Canal headed straight for the agricultural fields of Southern California’s Imperial Valley, the Boulder Canyon Project certainly addressed irrigation needs. But the project also tackled historic flooding problems on the lower Colorado River, controlled the storage and release of water for municipal and industrial use and, importantly, provided electric power for commercial sale to cities and industry far and wide. Hoover Dam and its powerplants would have a profound impact on urban growth from nearby Las Vegas, Nevada, to distant Los Angeles and San Diego, California.

Reclamation built the massive dam, installed the generators in its two powerplants, constructed the transformers in its switchyards, and then leased the rights to generate Hoover’s power to outside utility companies in Arizona, Nevada, and California, including Southern California Edison, the Los Angeles Bureau of Power and Light, and Southern Sierras Power Company. The utility companies built the transmission lines, substations, and other features needed to distribute the electric power.

In 1939, when the final of Hoover’s original nine generators was installed and placed in operation, the capacity of Hoover’s powerplant was 704,800 kilowatts, making it the largest hydroelectric powerplant in the world – a distinction held until surpassed by Grand Coulee Dam in 1949.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 13, 2017