The sun peaked at midday on June 10, 1944, as excavation crews working 3,000 feet beneath Rocky Mountain National Park saw a different light at the end of their tunnel. Four years had elapsed since they began digging the 9-foot tall channel—the linchpin of the Bureau of Reclamation’s Colorado-Big Thompson Project. Since 1940, two crews of men dug towards each other from both the east and west portals, to form the 13-mile Alva B. Adams Tunnel, named for the U. S. senator and project advocate. The tunnel pierced through the Rocky Mountains to carry water from the Colorado River on the western slope to the Big Thompson River on the eastern slope. When dust from the last dynamite blast settled, the two crews met for the first time under the Continental Divide, the tunnel’s alignment off by less than the height of a penny. It would be another three years—enough time to line the tunnel with concrete—before Colorado River water, pumped by electricity flowing from the Green Mountain Powerplant, made its first appearance on the East Slope.

Although the engineering obstacles of the Colorado-Big Thompson Project were great, historian William Rowley writes they “paled before the complications of local politics that pitted the West Slope of the Rockies against the East Slope.” The plan to divert Colorado River water across the Divide caused political controversy and raised legal questions that had to be resolved by compromise and compensation with the West Slope’s Green Mountain Dam and Powerplant before Reclamation’s project would be approved for construction. Furthermore, construction could impact Rocky Mountain National Park, sparking national debate about impacts on wildlife, habitat, and scenic value that foreshadowed environmental objections to Reclamation projects that arose in later years.

The headwaters of the Colorado River rise in the Never Summer mountain range of Colorado, 40 miles west of and across the Divide from Estes Park. Fed by Rocky Mountain snowmelt, it flows through western Colorado and Utah, then along the borders of Arizona and California, carving the Grand Canyon and passing through Hoover Dam’s powerplants, before emptying into Mexico’s Gulf of California, although the river now only reaches the gulf in exceptionally wet years because every drop is allotted to its 30 million users. It is one of the most controlled rivers on Earth, and regulation defining those controls includes the 1922 Colorado River Compact that allocated its flows between the upper basin (Colorado, Utah, Wyoming, Arizona, and New Mexico) and lower basin (California, Arizona, Nevada) states.

The idea of delivering Colorado River water to the eastern plains didn’t originate with the Bureau of Reclamation. In 1889, the State of Colorado had funded several trans-mountain diversion studies. Reclamation first considered it in 1905, but shelved the plan. It wasn’t until the late 1920s, with the Colorado economy hit hard by drought, that Reclamation revisited the trans-mountain water concept when U.S. Senator Alva B. Adams from Pueblo, Colorado, pushed for New Deal funding for a great water project for his state. At the same time, local agricultural and business interests in Weld and Larimer counties organized, raised funding, and hired engineers to further study the 1905 Federal trans-mountain diversion concept. In 1936, Reclamation prepared plans for construction of Granby Dam and reservoir to store water on the West slope and the Alva B. Adams Tunnel to transport 310,000 acre-feet of water to the east slope.

Soon, however, opposition arose from residents of western Colorado, who saw their future growth potential being siphoned off to support east-side growth. As the representative voice for western Colorado, Congressman Edward T. Taylor from Glenwood Springs, Colorado, blocked the project in Congress for three years. Taylor demanded that, if the trans-mountain project was to be approved, western Colorado must be compensated using the “acre-foot-for-acre-foot principle,” meaning the amount of river water diverted to the East Slope—310,000 acre feet—must be replaced by reservoir storage in the west. Both East Slope representatives and Reclamation felt Taylor’s demand was excessive, preferring only to replace the amount already used by West Slope farmers.

In the end, Western Colorado’s present and future water needs would be protected through “the Green Mountain Compromise,” which required the construction of a new reservoir, the Green Mountain Reservoir, built west of the Divide. Green Mountain Reservoir would store 152,000 acre-feet of water, of which 52,000 acre-feet were reserved for western Colorado use, while the remaining 100,000 acre-feet would be used to generate electricity at a new Green Mountain Powerplant to be built at the dam.

Along with dividing residents of the State of Colorado, the project also caused conflict between two Department of the Interior agencies, the Bureau of Reclamation and the National Park Service. Park Service personnel felt the Colorado-Big Thompson Project threatened Rocky Mountain National Park, and conflicted with the National Park Service mission to protect the country’s cultural and natural resources for public enjoyment. Although the west and east portals of the Adams Tunnel would be outside the boundaries of the park, many felt its construction, which involved the removal of 308,000 cubic yards of earth and installation of 4.2 million pounds of steel, would impair the park’s scenery, decrease visitation, and harm wildlife. Despite his fondness for parks, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes’s final decision was based upon Rocky Mountain National Park’s enabling legislation, which specifically stated that Reclamation may enter the park “for the development and maintenance of a Government Reclamation Project.” The controversy foreshadowed both the criticisms of Reclamation projects during the environmentalist movement of the 1960s and 1970s, yet also the efforts Reclamation took to respond to those concerns, such as alterations to design and sensitive construction methods.

In 1937, Congress approved the plan, and Reclamation was authorized to begin construction of the Colorado-Big Thompson Project. However, the obstacles for project approval and execution were compounded by financial bombshells during construction. Redesigns, in part to minimize impacts to Rocky Mountain National Park, and inflation increased cost, and World War II extended the timeline of the project. The proposed 6-year, $50 million project turned into a 19-year enterprise totaling more than $162 million. Although World War II halted construction on many Reclamation construction projects, work continued at the Green Mountain Dam and Powerplant after Reclamation argued that power for war materials plants and irrigation to increase crop yields were crucial to the war effort.

Reclamation selected a location 13 miles southeast of the town of Kremmling on the Blue River, a tributary of the Colorado, as the site for the new dam and powerplant. In October 1938, crews strung power lines from Dillon, one of the closest towns to the site’s remote location, to provide electricity at the Green Mountain Dam construction site, Reclamation’s tallest earth embankment dam at 274 feet high. Construction was also not without controversy—in 1939, the National Guard was called in to police a labor dispute between the workers and the contractors building the Green Mountain Dam. Five American Federation of Labor (AFL) craft unions demanded a closed shop, where only union members could be hired, and which after 41 days, the unions won. Dam and powerplant construction resumed, concluding in 1943. Thereafter electricity generated at Green Mountain Powerplant flowed to Denver manufacturing plants, mines, and other locations to support the war effort.

Located on the north side of the Blue River, at the downstream base of Green Mountain Dam, the flat-roofed, rectangular reinforced concrete powerplant is functional in design, and reflects the Modern architectural movement style. The building features horizontal projections and offsets at major points, as well as four elongated rectangular glass-block panels on its southwest side. Below these are four multi-pane steel sash windows, separated by concrete panels, that provide light and ventilation to the generator floor. The Green Mountain Powerplant’s two units generate 26,000 kilowatts.

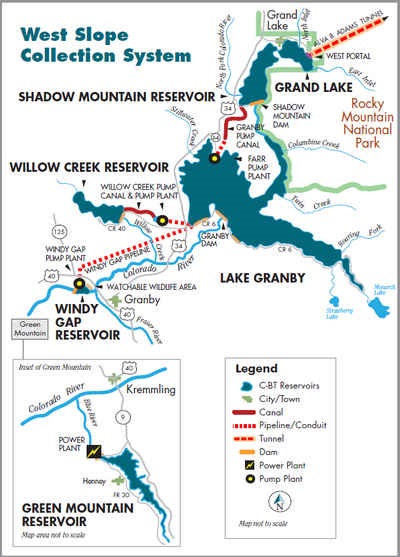

Although the water in Green Mountain Reservoir flowed west, it generated electricity that was transmitted east, to the Shadow Mountain Reservoir and Lake Granby pumping stations, to propel Colorado River water up the western slopes of the Rocky Mountains to Grand Lake, located on the western edge of Rocky Mountain National Park. From Grand Lake, water enters the Adams Tunnel, gradually dropping 109 feet by gravity flow from west to east. Once across the divide, Colorado River water flows into another network of tunnels, conduits, and pipes, powerplants, dams, and reservoirs, and then is carried by and distributed from the Big Thompson River, a tributary of South Platte River. Power that exceeded project need was sold, earning revenue to help repay construction costs. Today, Reclamation staff coordinates with Western Area Power Administration (WAPA) to supply “peaking power,” meaning it is used to meet the electric demand at times of high usage, typically mornings and evenings. Together, all six powerplants on the Colorado-Big Thompson Project generate enough electricity to serve over 58,000 homes.

In 1993, Reclamation and the Colorado State Historic Preservation Office agreed that Green Mountain Powerplant is eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places for its Modern architecture, and for its role in delivering west slope Colorado River water to east slope water users as part of the Colorado-Big Thompson Project, one of the largest and most complex systems ever to be built by the Bureau of Reclamation.

Visit the National Park Service Travel Bureau of Reclamation's Historic Water Projects to learn more about dams and powerplants.

Last updated: January 13, 2017