Last updated: December 31, 2020

Article

Women’s History at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition

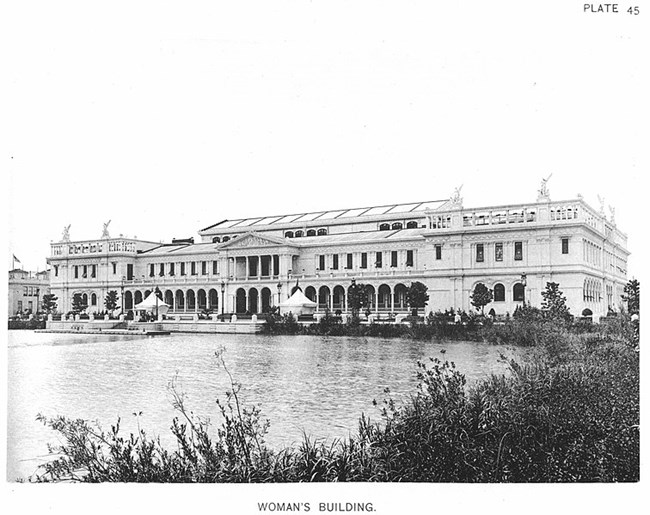

At the Exposition, women contributed to exhibits, spoke at events, and served in leadership roles. The Woman’s Building exclusively featured women’s accomplishments. Women produced all aspects of the building’s design, ornamentation, and content, including paintings, sculptures, and exhibits. Yet, some women critiqued the Woman’s Building; they argued that displaying women’s achievements separately suggested that they were secondary to men. Other activists protested the Exposition’s racist depictions of people of color. This article features the places associated with some of the ways that women were represented at the World’s Columbian Exposition.

Howe House

In 1891, the Exposition’s Construction Department held a design competition for the Woman’s Building. Only women with formal architectural training could participate. Twenty-one-year-old Sophia Hayden submitted the winning design. She was the first woman to earn a four-year architecture degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). During construction, Hayden suffered a “brain fever,” likely a nervous breakdown, from the pressure and the Board of Lady Managers’ demands. The Woman’s Building was her first and last realized building. Lois Lilley Howe received honorable mention in the competition. She completed the two-year “partial course” in architecture at MIT in 1890. Although her design was not chosen, Howe still reached an architectural milestone the year of the Exposition. In 1893, she established the first all-woman architectural firm in the U.S. By 1931, Howe became the first woman recognized as a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects.

Within a year, most Exposition structures, including the Woman’s Building, burnt down or were demolished. Lois Lilley Howe’s home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the Howe House, was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.

Palmer House Hotel

During the planning stage, some civically engaged, upper-class women pressured Exposition administrators for greater representation. As a result, Congress authorized and funded the Board of Lady Managers. The 117 Board members were the first women who served in an official capacity at a world’s fair. Yet, women were still excluded from any major decision-making. Socialite Bertha Honoré Palmer served as the Board’s president. Her husband, Potter Palmer, had built the Palmer House Hotel as her wedding gift. When Exposition organizers tasked Palmer with the concoction of a new portable dessert for the fair, she turned to the hotel’s kitchens. The chefs debuted their creation, the chocolate ‘brownie,’ at the Exposition. Five years later, a Sears Roebuck catalog published the first mention of the ‘brownie’ by name.

The first Palmer House Hotel was built in 1871, and stood less than two weeks before burning down in the Great Chicago Fire. The second Palmer House Hotel, where the brownie was created, was completed in 1875. In the 1920s, it was demolished to make way for a larger, third Palmer House Hotel on the same site. The third Palmer House Hotel still stands. It was designated a Chicago Landmark in 2006. Chicago is part of the Certified Local Government Program, a certified partnership between federal, state, and local governments that supports local communities’ commitment to historic preservation.

Jackson Park Historic Landscape District and Midway Plaisance

Exposition organizers separated the main exhibition buildings from the Midway Plaisance, where they displayed sideshows and curiosities. At the Midway, organizers also exhibited many non-European cultures as racist stereotypes or relics of the past. The few exhibition buildings that featured people of color also conveyed themes of white supremacy. The Board of Lady Managers refused to exhibit Black women’s accomplishments on their own. Instead, the Woman’s Building depicted Black, Native American, and Polynesian women in the “Woman’s Work in Savagery” exhibit. African American activists Ida B. Wells, Fannie Barrier Williams, and Frederick Douglass objected vehemently. Because the Exposition celebrated 'civilization,’ Wells argued that the exclusion of Black people’s achievements suggested that Black people were not civilized.

The Jackson Park Historic Landscape District and Midway Plaisance were listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1972.

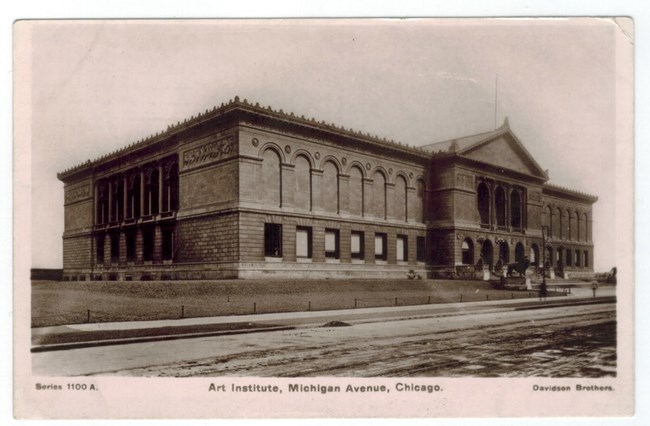

Art Institute of Chicago

During the Exposition, the World’s Congress Auxiliary hosted over 100 congresses about cultural and scholarly topics. The congresses assembled in a new building in Grant Park, which became home to the Art Institute of Chicago after the Exposition. At the weeklong World’s Congress of Representative Women, the Woman’s Branch of the Auxiliary welcomed 150,000 people, including 500 speakers from 27 countries. The speakers included Susan B. Anthony, Lucy Stone, and Julia Ward Howe, leaders in the American women’s suffrage movement. At the congress, Anthony delivered a speech by Elizabeth Cady Stanton calling for the “Civil and Social Evolution of Women.” She declared, “the woman must be brought to a common denominator with man, and be considered invariably as a human being.”

The Art Institute of Chicago is a contributing building in the Historic Michigan Boulevard District, which is a Chicago Landmark.

Lorado Taft Midway Studios

Sculptor and instructor Lorado Taft was the Exposition’s superintendent of sculpture. He asked Daniel Burnham, the Director of Works, if he could hire his best female students from the School of the Art Institute to assist him. Burnham reportedly told Taft to hire, “even white rabbits” if they did the work. The team of women adopted the nickname, “White Rabbits” and worked out of Taft’s studio in the Horticultural Building. They produced monumental works, including The Sleep of the Flowers, and decorative sculptures that adorned several exhibition buildings. Many of the White Rabbits, including Janet Scudder, Julia Bracken, Carol Brooks, Enid Yandell, and Taft’s sister Zulime, became leading American sculptors.

The Lorado Taft Midway Studios were designated a National Historic Landmark in 1965 and listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1966.

Selected Sources:

Ballard, Barbara J. “A People Without a Nation: African Americans at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition.” (.pdf) Chicago History Magazine (Summer 1999): 27-43.

Gullett, Gayle. “‘Our Great Opportunity’: Organized Women Advance Women's Work at the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893.” Illinois Historical Journal 87, no. 4 (1994): 259-76. Accessed November 1, 2020.

McLeod, Mary and Victoria Rosner, eds. “Sophia Gregoria Hayden Bennett.” Pioneering Woman of American Architecture. Accessed November 9, 2020.

WTTW (PBS). “White Rabbits.” Art & Design in Chicago. Accessed November 9, 2020.