Last updated: July 28, 2025

Article

Washington’s Cambridge Headquarters and the Memory of the American Revolution

In 1775 the Longfellow House became the center of an emergent revolution when George Washington arrived in Cambridge and moved into the newly designated headquarters in the Brattle Street mansion formerly owned by loyalist John Vassall.

For the next eight months, the house buzzed with activity as Washington directed the Siege of Boston. Within its walls, Washington and his advisors devised military strategies, debated political matters, and pursued diplomatic efforts. It was here, on January 2, 1776, that the phrase “the United States of America” appeared in writing for the first time, an early reflection of the growing conviction that the Revolution was a path to independence and an emerging vision of national unity.

The significance of the events and figures tied to the house during the Revolution resonated beyond its time, inspiring poets, historians, and preservationists to commemorate its place in American history. Prominent among them was Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who sought to build a national literary tradition by capturing uniquely American stories. In doing so, he and others not only told these tales, with varying degrees of accuracy, but became part of the story themselves.

Washington’s Headquarters

Evidence of this house’s use as Washington’s Headquarters comes from written records and archeological finds. It was a bustling place with military officers, administrative staff, free and enslaved laborers, representatives from Congress in Philadelphia, delegations from Massachusetts and the other colonies, and other interested parties constantly coming and going.

NPS Photo

Shell

The Longfellows believed this shell was “fired by the British from besieged Boston.” Though it is unlikely a projectile landed here, sounds of cannon certainly reached Headquarters. In December 1775, Martha Washington reported, “a number of cannon and shells from Boston and Bunkers Hill...does not seem to surprise any one but me.” Longfellow family tradition held that it was found in Cambridge, possibly at Fort Washington or Fort Putnam.

NPS Photo / James Jones | Photography RI

Bayonet

Recovered by a gardener prior to 1930, this French pattern bayonet may have belonged to a guard at Washington’s Headquarters. It features a socket mount with an offset blade, allowing the musket to be fired with the bayonet attached.

NPS Photo

Wine Bottles, about 1776

Archeological work in the house’s basement revealed fragments of wine bottles made around 1776, aligned with Washington’s residency. Archeologists estimated the date based on analysis of eight bottle bases and 20 fragments of necks and rims. Orders of wine were among the largest expenses on Headquarters’ accounts.

H.W.L. Dana Papers, Miscellaneous Famous People

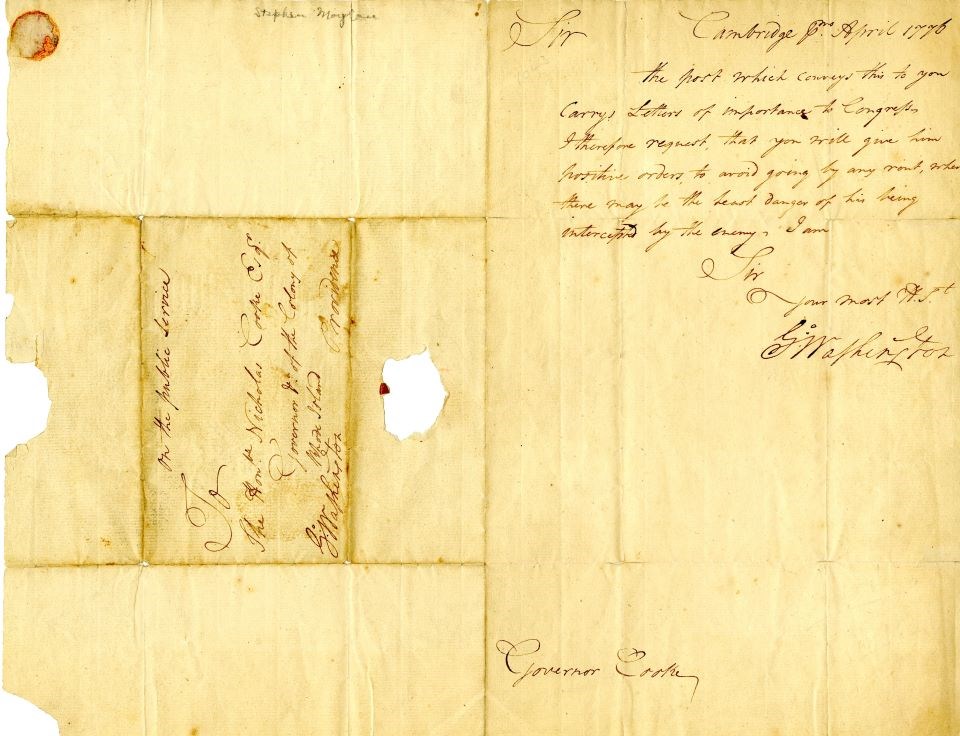

Letter, Washington to Cooke, 4 April 1776

Washington’s letter to Rhode Island’s governor illustrates the serious business conducted at Headquarters. Washington asks Cooke to send a courier bearing “Letters of importance to Congress” along a safe route to avoid capture.

A pencil annotation attributes the handwriting in the body of the letter to Stephen Moylan, Washington’s aide-de-camp from 6 March to 5 June 1776.

Museum Collection (LONG 4656, LONG 21171)

Legacy of Headquarters

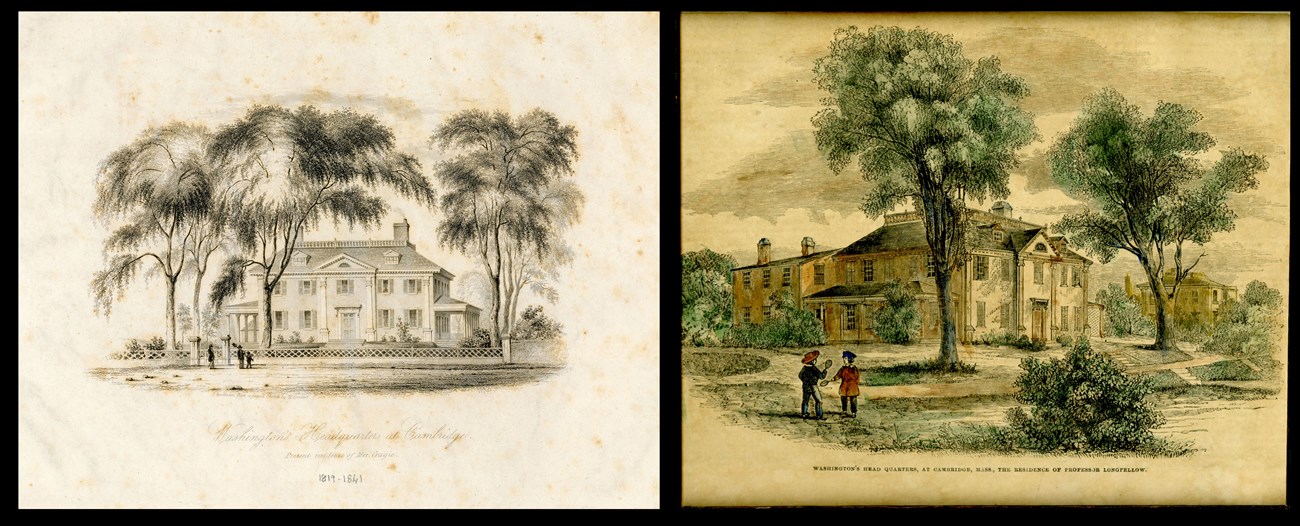

Washington’s Headquarters in Cambridge became an attraction almost as soon as the Revolution ended, sparking public interest, tourism, and souvenirs. The Longfellows took pride in their home’s association, claiming in 1844 they had “no desire to change a feature...which Washington has rendered sacred.” The significance of Washington’s residency continued to be recognized by their descendants and the public.

The façade of the house became a popular subject for prints in the mid-1800s. In captions, the house’s association with Washington receives top billing, with the names of later residents Elizabeth Craigie and Henry Longfellow as afterthoughts.

In 1875 Edith Longfellow joked that she seemed “Centennial cracked.” In a letter to her younger sister, written from “Head Quarters,” Edith gushed about living in the house where Washington resided:

I wander about as in a dream and live not in the present, but a hundred years ago. It all seems like a beautiful romance – the white balustrade leading down and the dark shade of the trees, the moonlight on the terrace, the broad stairs descending to the open front door – and the hero of the romance my joy and admiration, the man of my heart, so noble, so true, so firm and yet so gentle is – Washington!

My centennial enthusiasm has reached a pitch never attained before. My new interest and excitement is reading all about this summer 100 years ago in Sparks and Irving, and every day I read the letters for that date, written certainly in this very room and probably by this very window where I write by Dear George! Think what a privilege to spend this summer of all others in this house. I would not have missed it on any account and think it ought to have influenced us to stay under any circumstances. People go over land and sea to see just the place where some great man was born or died, and here all day long I can walk the floors this greatest of men to us Americans stood... and at night I sleep in his very room and see the moon over the river as he must have seen it, and in the morning the Brighton meadows stretching bright under the summer sun.

... All the interest of these Centennials will drift away from us so soon that it seems to me we cannot make too much of these most interesting associations so peculiarly and closely connected with this town and house. Don’t please think me Centennial cracked but forgive this outburst and I will try to descend from my high flight to the present.

NPS Photo

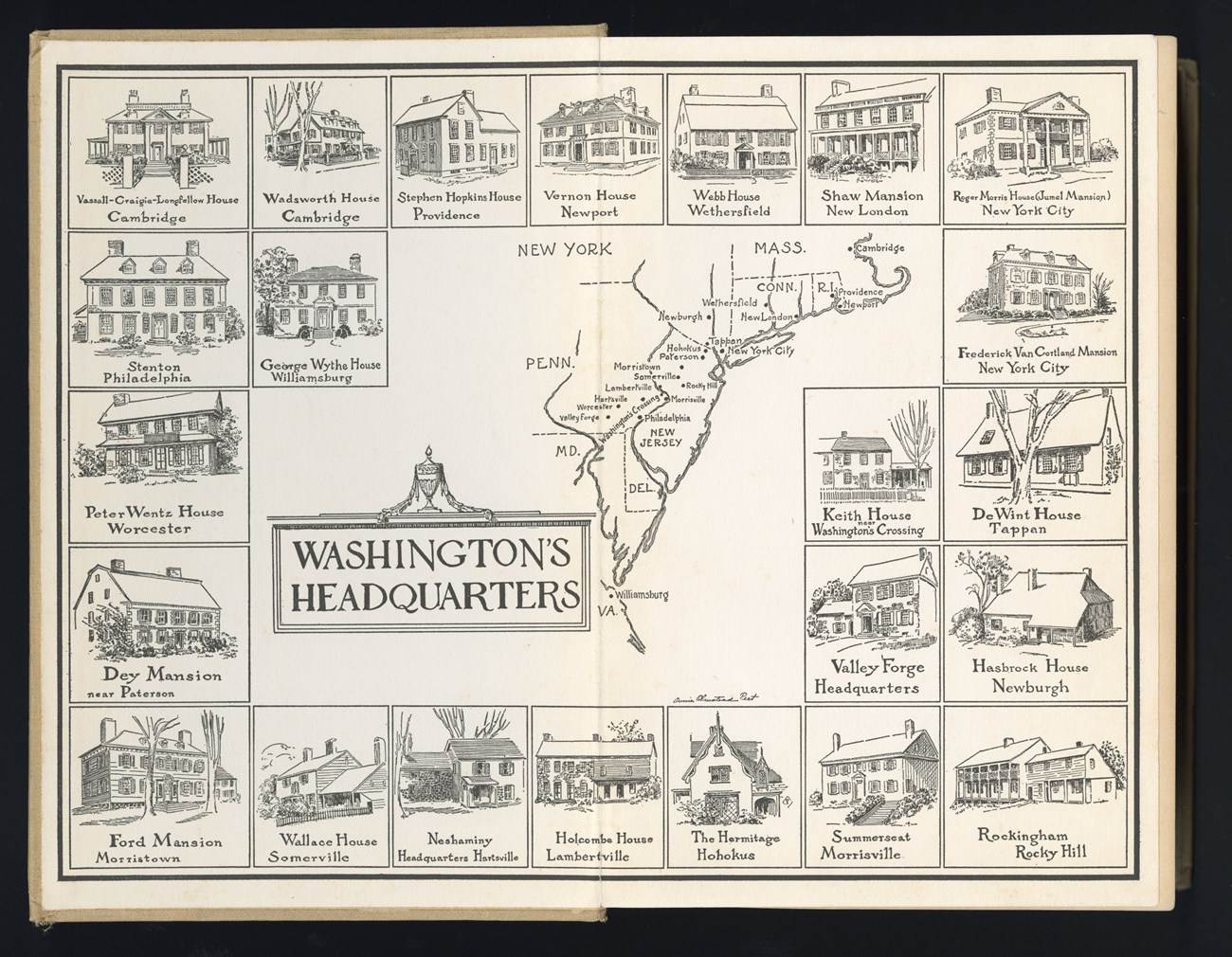

Mabel Ives’s chatty guidebook, Washington's Headquarters, includes the 24 headquarters still standing and open to visitors in 1932. Her chapter on “the best-known home in New England” covers the history of this house prior to, during, and after Washington’s residency.

In 1940, the Daughters of the American Revolution received permission from the Longfellow descendant then overseeing the house to host a “Guest Day” event at the house. In her request for the event, the regent for the local Hannah Winthrop Chapter wrote, "I need not tell you how deeply we appreciate such a privilege and hope we have not outworn our welcome." Their invitation noted the significance of the setting by calling it “Longfellow House (Washington’s Headquarters).”

Paul Revere's Ride

Henry Longfellow's poem “Paul Revere’s Ride” was a call for unity on the eve of the American Civil War. Longfellow drew upon the American Revolution for its setting and elevated Revere’s status to that of a near-mythic American hero, arguably at the expense of other, equally significant figures. A sensation from its publication in December 1860, the poem made Paul Revere and his ride an indelible American symbol:

Listen, my children, and you shall hear

Of the midnight ride of Paul Revere,

On the eighteenth of April, in Seventy-five;

Hardly a man is now alive

Who remembers that famous day and year.

NPS Photo

HMS Somerset Fragment

This fragment of wood illustrates the complicated entanglement of fact and myth around Paul Revere's historic ride and the poem. Paul Revere was rowed past HMS Somerset in Boston Harbor on the night of April 18, 1775. Longfellow's poem describes:

Where swinging wide at her moorings lay

The Somerset, British man-of-war;

A phantom ship, with each mast and spar

Across the moon like a prison bar,

And a huge black hulk, that was magnified

By its own reflection in the tide.

This British warship wrecked off Cape Cod in 1778. Almost a century later, an admirer sent this fragment from the resurfaced wreck to Longfellow.

William Dawes & his Ride with Paul Revere, 1878

Longfellow’s promotion of Revere received backlash from Henry W. Holland, great-grandson of Revere’s fellow rider William Dawes. In 1876 Holland delivered a lecture to the New England Historical Genealogical Society highlighting Dawes’s role. After its publication Longfellow remarked of Holland, “he convicts me of high historic crimes and misdemeanors.”

NPS Photo

The Paul Revere Album, 1897

In 1897 the Howard Spurr Coffee Co. printed The Paul Revere Album, billed as “The Greatest Advertising Offer of the Nineteenth Century!” The company’s Revere trademark is featured throughout, as are excerpts from Longfellow’s poem. The Howard Spurr Coffee Co. encouraged customers to collect “Trade Marks”–featuring an image of Revere's ride–from bags of the company’s coffee, which could be redeemed for a biography of Paul Revere.

Museum Collection (LONG 23076)

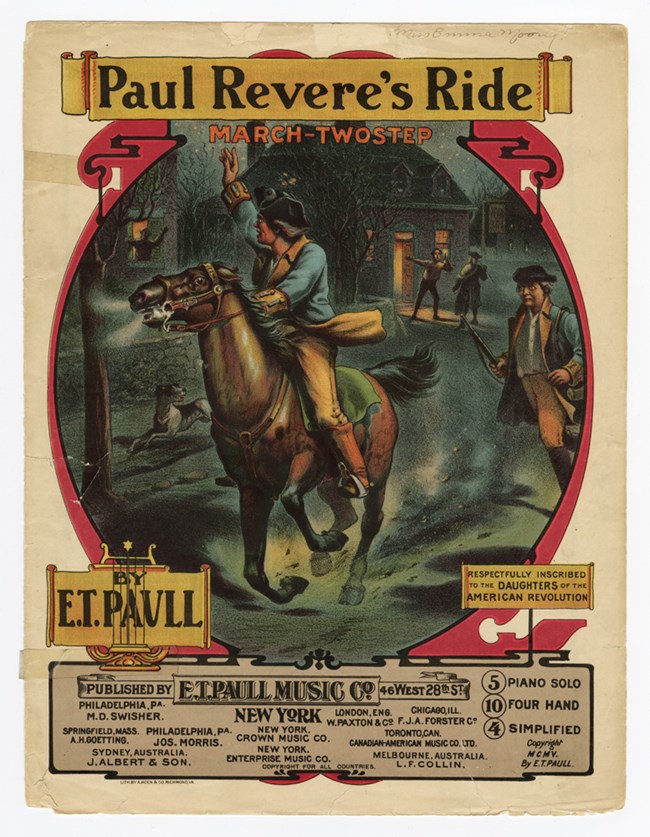

Sheet Music, 1905

Longfellow’s poem inspired a host of derivatives, including this colorfully illustrated piece of sheet music by E.T. Paull. "Paul Revere's Ride: March-Galop" interprets the poem as a instrumental piano piece. Though it has no words, the instructions to the player note when the music should suggest a horse galloping, a cry of alarm, and the Battle of Lexington and Concord. Paull boosted the piece’s patriotism by dedicating it to the Daughters of the American Revolution.

Paul Revere’s Ride, 1907

Longfellow’s poem created enduring interest in Paul Revere. Efforts to preserve Revere's Boston home began in 1902, and it opened as a museum in 1908. A Paul Revere House Souvenir Edition of Paul Revere's Ride may have been a fundraiser or an early gift shop item.

Museum Collection (LONG 15397)

Midnight Ride of Paul Revere, 1937

Published by Beatrice F. Morse and printed by Adams Press, both of Lexington, Massachusetts, this 1937 booklet of “Paul Revere’s Ride” was perhaps a projection of hometown pride. The stick figure illustrations are by the enigmatic Dinah Kirk.

Centennial & Commemoration: 1873-1876

Boston and its suburbs celebrated the Centennial of the American Revolution with speeches, poetry, fanfare, and dinners. Key events in 1875 included orations in Lexington and the dedication of the Minute Man statue in Concord on April 19, a Bunker Hill Day parade on June 17, and Cambridge’s celebration of Washington’s arrival on July 3. Henry Longfellow read and commented on the speeches, and his family attended several events.

A flurry of books accompanied the Centennial events and excitement. Authors used the moment to document the Revolution’s history. Town publications placed emphasis on the planning, speeches, and personalities involved in 1875.

Cambridge poet James Russell Lowell composed poems for centennial anniversaries at Concord, Cambridge, and for the “Fourth of July, 1876.” These patriotic poems were published in 1877 as Three Memorial Poems. Longfellow found the "Concord Ode" very good, remarking, “He has a gift for that kind of composition.”

Museum Collection (LONG 18023)

Boston Tea Party Cup, December 1873

This cup is a souvenir of the Boston Ladies’ Tea Party in Faneuil Hall, a celebration of the Centennial with a children’s choir, speeches, an Emerson poem, and refreshments including tea. Suffrage leaders held the New England Woman’s Tea Party the night before in the same space, where speakers claimed the legacy and rhetoric of the Revolution in protesting women’s “taxation without representation.”

Museum Collection (LONG 7194)

Commemorative Medal, 1876

The public drew on Henry Longfellow’s writing for centennial celebrations. The Women’s Centennial Committee of Boston gave him this gold medal featuring a line from his poem “The Building of the Ship” as a patriotic motto: "Sail on O Union Strong and Great."

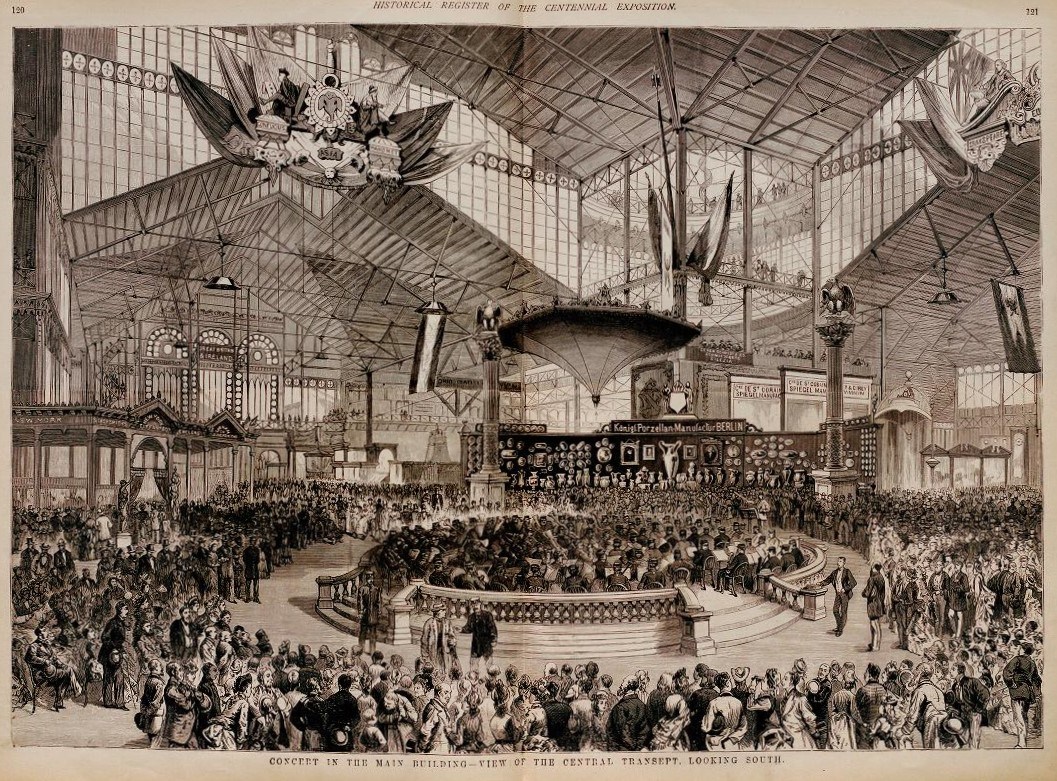

Centennial Exposition, 1876

Nominally to mark the anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia ran for six months and featured exhibits from around the world. The Longfellows visited for a week in May 1876, taking in the art, music, technology, and food.

Frank Leslie's historical register of the United States Centennial Exposition, 1876. New York: Frank Leslie's Publishing House. Smithsonian Libraries.

Biographers and Biographies

In the 1800s, memory of the Revolution turned into history and mythology. Early biographers focused on the perspectives of the military and political leaders.

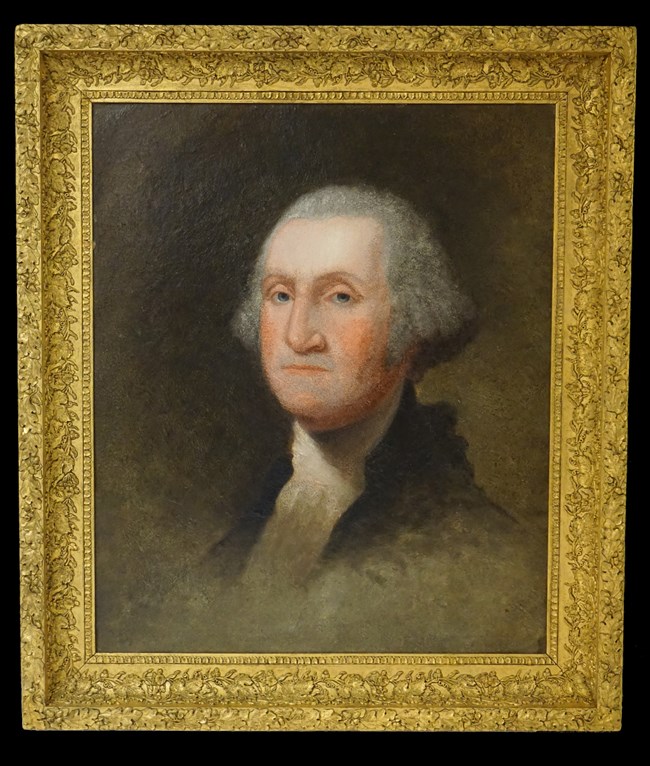

General George Washington (1732-1799)

Many biographers have written Washington’s story. While living in Headquarters as a boarder of then-owner Elizabeth Craigie, historian Jared Sparks edited the first collection of Washington’s letters, published in 1834-37. In 1843, he sought out first-hand knowledge of Washington’s occupancy by writing to Trumbull, who had been an aide at Headquarters in July 1775. Another key early biography, Washington Irving’s 1855 Life of George Washington, included stories of dubious veracity.

Despite their editorial license, Sparks and Irving remained the most successful and significant Washington biographers. In 1875, Edith Longfellow relied on these sources for her enthusiasm for "reading all about this summer 100 years ago" and following along in Washington's correspondence.

Museum Collection (LONG 6049)

As general and president, George Washington represented the fledgling American experiment and his image remains one of the most enduring emblems of the United States. Following the American Revolution, portrayals of him flooded the market, none more iconic than the three painted by Gilbert Stuart, one of which adorns the dollar bill. Stuart and his daughter created hundreds of copies of these images.

This painting is likely one of Jane Stuart’s copies of her father’s famous Athenaeum portrait of Washington. The portrait was owned by generations of the Dana family of Cambridge. In the 1940s, it hung in the front hall of the Longfellow House near a copy of Houdon's bust of Washington. The strange surface texture around the face may be the result of a failed cleaning attempt.

Museum Collection (LONG 19681)

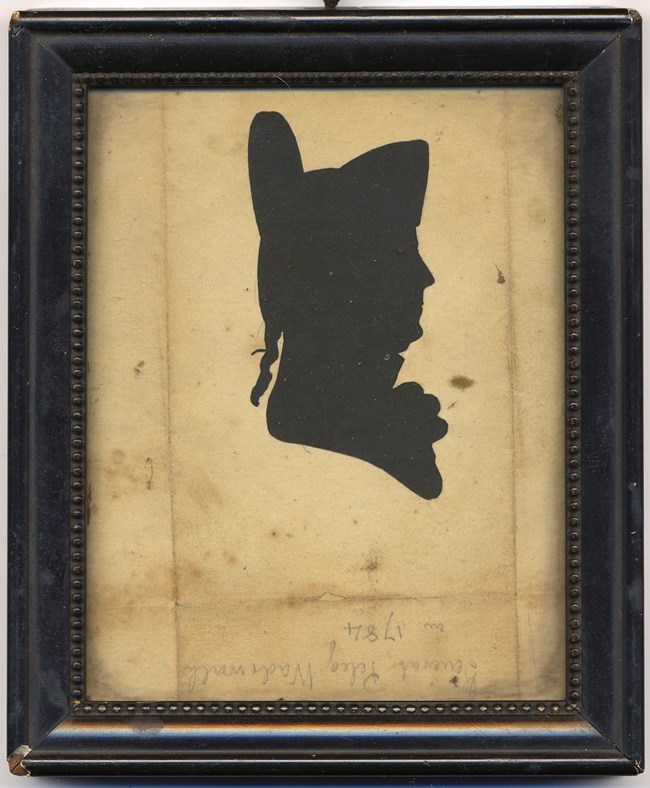

General Peleg Wadsworth (1748-1829)

Henry Longfellow’s maternal grandfather passed on his account of military service in stories told to his family, particularly of a daring escape after his capture by the British in Maine. His great-granddaughter Alice Longfellow traced her membership and activity in the Daughters of the American Revolution to his service.

General Nathanael Greene (1742-1786)

Henry Longfellow supported the effort of his friend George Washington Greene–like him, the grandson of a Revolutionary War general–to publish a biography of his ancestor. Greene and Longfellow toured the Continental lines around Boston in 1843, "under Mr Spark’s admirable guidance," because Greene "is greatly interested in tracing his Grandfather’s quarters in this neighborhood."

In 1846, George Washington published Life of Nathanael Greene, Major-General in the Army of the Revolution as a volume in The Library of American Biography series, edited by Jared Sparks.

Museum Collection (LONG 36353)

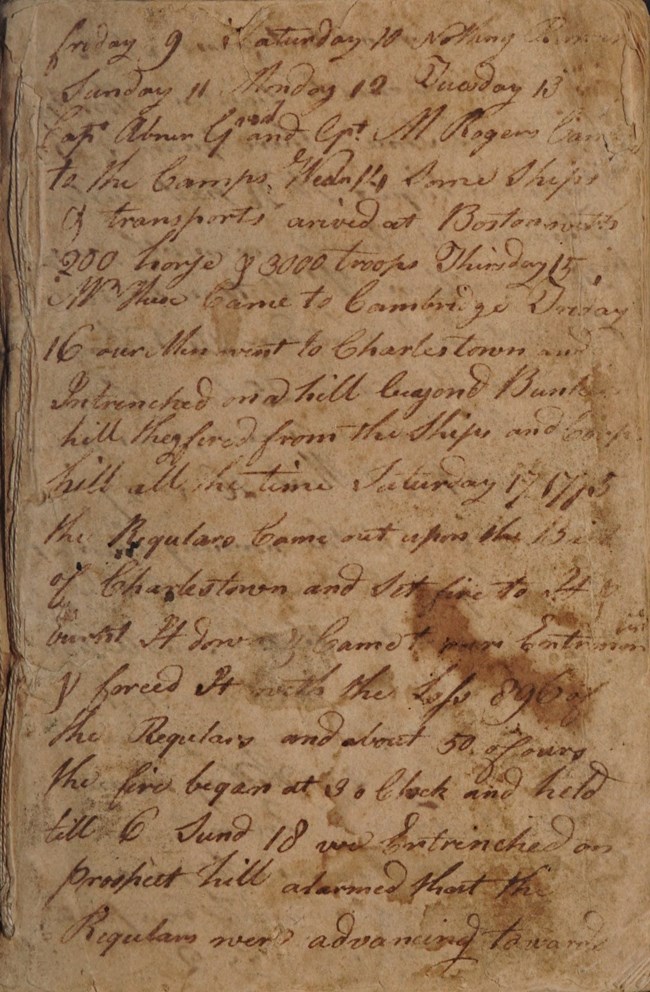

Caleb Haskell and Moses Sleeper

Caleb Haskell and Corporal Moses Sleeper both enlisted from Newburyport and documented the Siege of Boston in their manuscript journals. Haskell’s account was published in 1881. Sleeper’s diary ended up in the collection of Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS, unpublished and anonymous until 1997.

Both Sleeper and Haskell's journals document the often-monotonous life in camp, as well as their participation in significant battles and marches. The preservation and publication of their journals by later generations allow insight into the perspectives of these otherwise-anonymous eyewitnesses to the opening of the American Revolutionary War.

Museum Collection (LONG 4373)

The Myth of the Washington Elm

The myth of an elm tree on the Cambridge Common bearing witness to Washington taking command captured public imagination. The tree became a landmark, widely illustrated in photographs, souvenirs, and artwork.

Henry Longfellow, like many Victorians, saved and documented pieces of the tree for their supposed association with Washington. Despite efforts to save the “original” elm, it fell in 1923 and fragments were distributed as souvenirs.

Museum Collection (LONG 17769, LONG 7383, LONG 7384)

NPS Photo

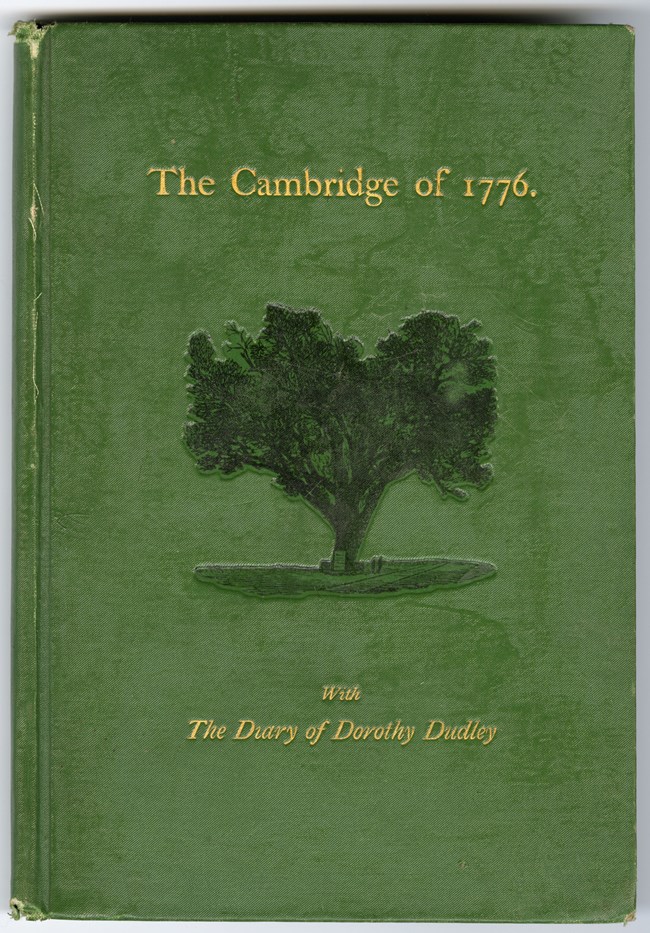

Though some have assumed it is authentic, the Diary of Dorothy Dudley was a project of the 1875 Ladies Centennial Committee of Cambridge, for which Alice Longfellow served as Secretary. Penned by Mary Williams Greeley, it began and perpetuated many of the myths of Cambridge Revolutionary history, including the Washington Elm.

The elm appears on the book's cover, and the fictional diary entry for July 3, 1775 describes a ceremony that stirred the public imagination despite its departure from original primary source descriptions:

It was a magnificent sight. The majestic figure of the General, mounted upon his horse beneath the wide-spreading branches of the patriarch tree; the multitude thronging the plain around, and the houses filled with interested spectators of the scene, while the air rung with shouts of enthusiastic welcome, as he drew his sword, and thus declared himself Commander-in-chief of the Continental army. He will find his task a hard one, that of making an army out of the rude material gathered from all parts of our Colonies.

Museum Collection (LONG 6719)

Mount Vernon Ladies Association

Founded to save George Washington’s Virginia home from ruin, the Mount Vernon Ladies Association transformed the property into a monument to the American hero. Alice Longfellow was the longest serving vice regent of the organization, from 1879 to 1928. Her work preserving both Mount Vernon and her own home–Washington's Cambridge headquarters–mutually informed one another and illustrate the importance of women in shaping American cultural memory.

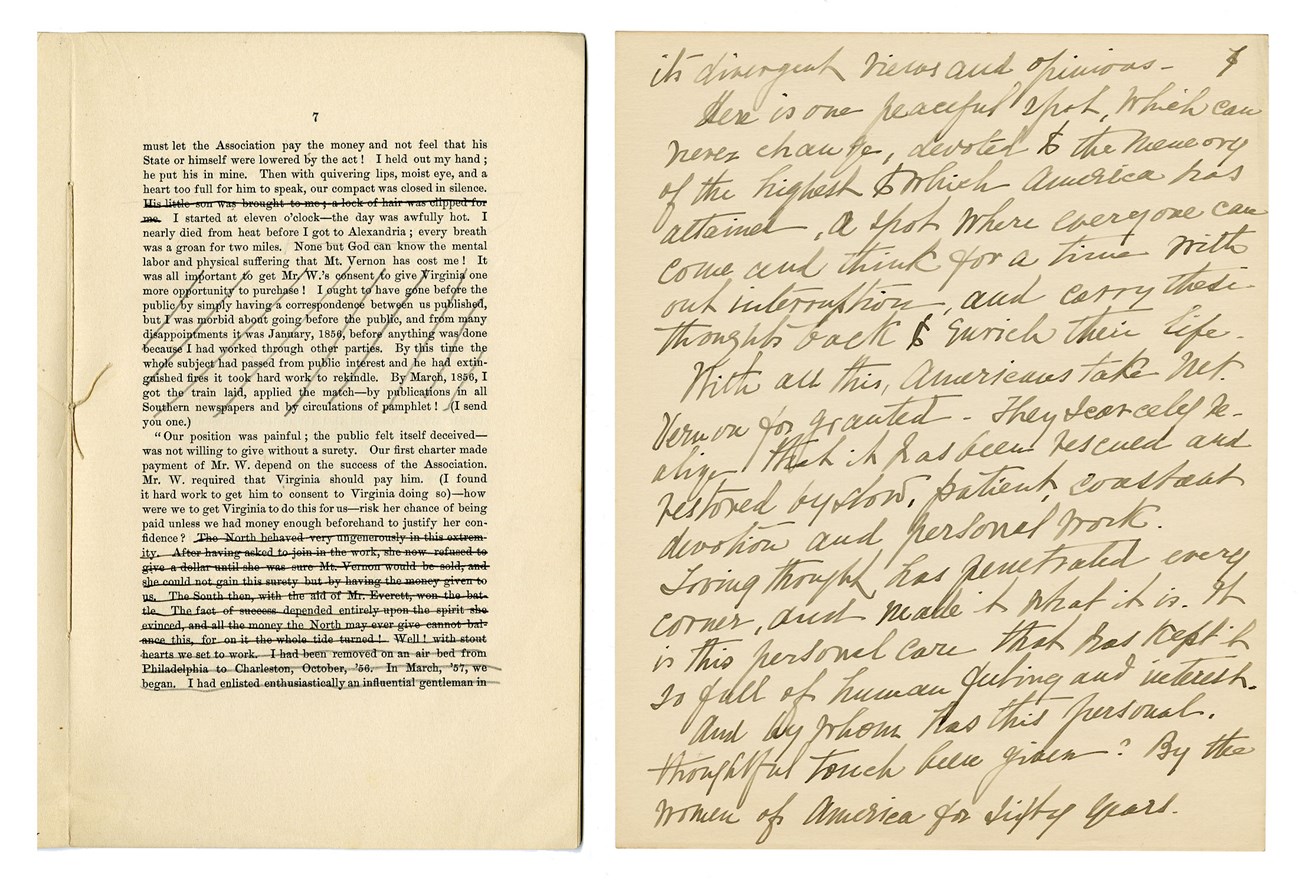

Alice Mary Longfellow Papers

In 1866, the Mount Vernon Ladies Association published a booklet featuring a letter by founder Ann Pamela Cunningham of South Carolina, giving an "interesting recital of her trials and difficulties in securing possession of Mount Vernon." Alice Longfellow marked up her copy of the booklet to use in her own essay on Mount Vernon in about 1917. Though Longfellow excised Cunningham’s derogatory comments towards “Northern women,” Longfellow’s manuscript still described tension between Northern and Southern women, both claiming ownership of Washington’s history.

Longfellow's "The Appeal of Mount Vernon" asserts:

The spirit of the Past asserts itself strongly over the present. … Everything that is false and trivial seems to drop away from people, and they see new visions—Mt. Vernon is truly a searcher of souls. Think what all this means to a country like America, with its constant change and stress of life—its many countries in one—its divergent views and opinions.

Museum Collection (LONG 2446)

To support Mount Vernon’s restoration, each vice regent for the Mount Vernon Ladies Association adopted a room to rehabilitate. As Vice Regent for Massachusetts, Alice Longfellow took charge of the study, raising funds and soliciting donations of objects, including books.

In 1897 Alice Longfellow loaned Mount Vernon a secretary desk from her home to furnish Washington’s study. By 1904 she had purchased Washington’s own secretary for Mount Vernon. Her loaned piece then furnished Mount Vernon's sitting room until 1921, when it was shipped back to her Cambridge home.

Alice Mary Longfellow Papers (1007.2/2.2-#19)

This photograph marks the 1921 visit of the Virginia Governor and his “Board of Visitors” to the Mount Vernon Ladies Association Annual meeting. The purpose of the Board was to review the operation of Mount Vernon and report the findings to the Governor. There were two critical issues at this meeting. The first was talk of Congressional control of Mount Vernon – which was universally opposed by both the Board and the Ladies Association. The second issue had to do with admission fees. At the time, admission to Mount Vernon cost 25 cents but there were rumblings about making admission free. While the governor seemed open to eliminating the fee and adding appropriations from the state, the board of visitors was less interested. One board member opposed it “as being an invitation to ‘vandals and the riffraff who would turn the sacred place into a picnic grounds.” He also noted that it was impractical in terms of maintaining the site and had opposition across the state.

As a long-serving member of the association, Alice Longfellow saw changes in the makeup of the vice regents and the preservation mission. Writing on Mount Vernon letterhead in 1915, she reflected on her 34 years of service: “I came here today & feel like the last leaf on the tree, only one other V.R. who was here when I first came - & such a change...”

Shaping the Narrative – Memory & Myth

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, Americans molded the narrative of their nation’s founding. Their choices as they wrote academic histories, commemorative poems, and literary stories influence our understanding of the revolutionary era today.

This generation shaped the national memory not only through their words, but also by physical commemoration in wood, bronze, and stone. Fundraising efforts led to the construction of landmarks such as the Bunker Hill Monument, the Dorchester Heights tower, and Daniel Chester French’s statue of “The Minute Man” in Concord. Contributions also supported building and conservation projects, including the reconstruction of the Old North Bridge and the restoration of George Washington’s home at Mount Vernon. Though the Longfellow House remained a private residence, the Longfellow family honored its history as Washington’s Cambridge Headquarters through both imagery and careful preservation.

The landscape of Greater Boston and the nation’s understanding of its own past still reflects the choices made by earlier Americans. Yet history is never static. Each generation faces its own decisions about what to preserve, what to remember, and how to tell its story.