Last updated: January 7, 2022

Article

Overview of the Urban Forests

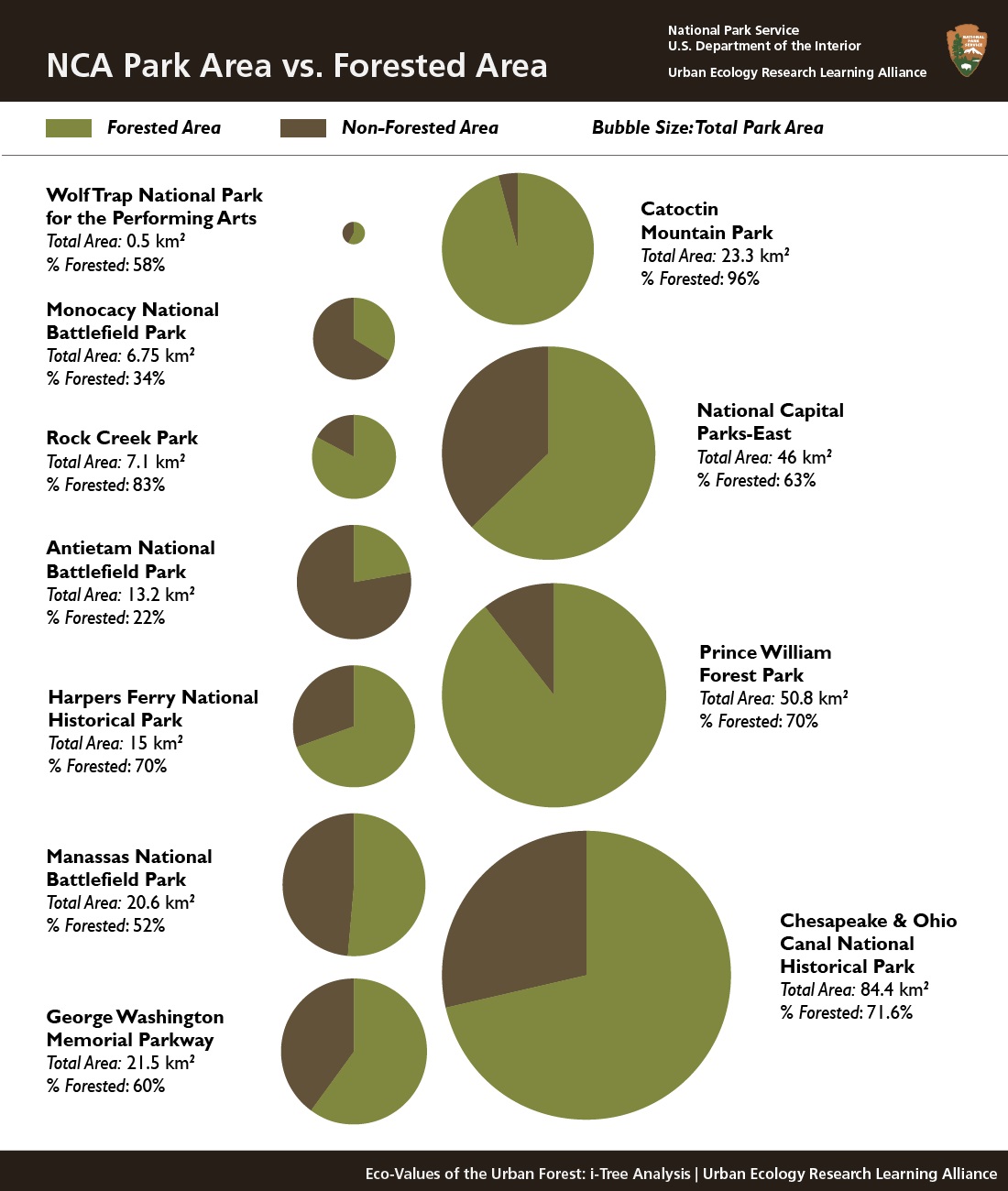

From the trees overlooking Antietam National Battlefield to those lining the metropolitan streets of the George Washington Memorial Parkway, the urban forests in the National Capital Area are diverse. Urban forests come in many different varieties and sizes — even landscaped boulevards can be part of the urban forest! With the i-Tree analysis, UERLA looked several National Capital Area park forests. The following pages explore just a few of the common ecological benefits the urban trees in these parks provide to the parks and the surrounding areas.

Air Pollution Removal | Carbon Storage | Avoided Runoff | Structural Values | Other Tree Benefits

Urban Forests in the National Capital Area

| National Park | Park Area (km2) | % Forested | Top Three Tree Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antietam National Battlefield Park | 13.2 | 22.3% | Boxelder, Northern Hackberry, Black Cherry |

| Catoctin Mountain Park | 23.3 | 96.0% | |

| Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park | 84.4 | 71.6% | Boxelder, Silver Maple, American Elm |

| George Washington Memorial Parkway | 21.5 | 60.2% | Red Maple, Tulip Tree, Pumpkin Ash |

| Harpers Ferry National Historical Park | 15 | 69.7% | Red Maple, Chestnut Oak, Black Tulepo |

| Manassas National Battlefield Park | 20.6 | 51.6% | American Elm, Eastern Red Cedar, White Ash |

| Monocacy National Battlefield Park | 6.75 | 34.0% | |

| National Capital Parks-East | 46 | 63.0% | Red Maple, Black Tulepo, Sweetgum |

| Prince William Forest Park | 50.8 | 89.5% | Tulip Tree, American Beech, Virginia Pine |

| Rock Creek Park | 7.1 | 83.0% | Red Maple, Sugar Maple, Chestnut Oak |

| Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts | 0.5 | 58.2% | Chestnut Oak, Tulip Tree, Virginia Pine |

Important Traits of an Urban Forest

Tree Density: Density of a forest plays a major role in the forest makeup, from the type of species that are more successful to the health of the forest. A denser forest has more competition for water, sunlight, nutrients, and other vital resources.Trees Size: The diameter of trees is one factor by which trees can be classified, and the proportion of small trees plays into evaluating forest health. Trees which have grown larger will store and sequester more carbon and are less vulnerable than smaller trees.

Tree Variety: Urban forests often have a tree diversity that is higher than surrounding native landscapes because they are composed of a mix of native and exotic tree species. Different trees species can provide different levels benefits based on factors like their growth and level of maintenance required.

About iTree

- Urban forest structure (e.g., species composition, tree health, leaf area, etc.).

- Amount of pollution removed hourly by the urban forest, and its associated percent air quality improvement throughout a year.

- Total carbon stored and net carbon annually sequestered.

- Effects of trees on building energy use and consequent effects on carbon dioxide emissions from power sources.

- Structural value of the forest, as well as the value for air pollution removal and carbon storage and sequestration.

- Potential impact of infestations by pests, such as Asian longhorned beetle, emerald ash borer, gypsy moth, and Dutch elm disease.

Next page: Air Pollution

UERLA Main Page: Eco-Values of the Urban Forest

References

Ferguson, K. (2017). UERLA Resource Brief: Ecobenefits of National Capital Region Park Trees. Retrieved from https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2290091.

Garner, J. (2018). UERLA Resource Brief: Quantifying Ecological Benefits of Trees in the National Capital Region. Retrieved from https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2290092.

Ingram, K. (2014). The effects of density and high severity fire on tree and forest health. Retrieved from https://ucanr.edu/blogs/blogcore/postdetail.cfm?postnum=15867

Nowak, D.J., Hoehn, R. E. III, Crane, D. E., Stevens, J. C., & Walton, J. T. (2006). Assessing urban forest effects and values, Washington, D.C.''s urban forest. Retrieved from https://www.fs.usda.gov/treesearch/pubs/18406.

Urban Ecology Research Learning Alliance. (2018). i-Tree Ecosystem Analysis: Urban Forest Effects and Values. Retrieved from https://irma.nps.gov/DataStore/Reference/Profile/2290090.

U.S. Forest Service. (2020). About | i-Tree. Retrieved from https://www.itreetools.org/about

Tags

- antietam national battlefield

- chesapeake & ohio canal national historical park

- george washington memorial parkway

- harpers ferry national historical park

- manassas national battlefield park

- national capital parks-east

- prince william forest park

- wolf trap national park for the performing arts

- uerla

- rlc

- trees

- urban forest

- forest

- ecosystem services

- park science

- nca

- ncr