Last updated: May 4, 2021

Article

Two for the Price of One

Companion, assistant, confidant, ambassador, host, nurse, cook, secretary, editor, field technician, wildlife wrangler, diplomat, and social director are some of the many roles that people who marry into the NPS perform in support of their spouses and the NPS mission. Although the wives and daughters of park rangers were some of the earliest women rangers in the NPS, many more women served as “park wives” in the 1920s–1940s. Working without pay, these women brought their talents and tenacity to the NPS, established and maintained park communities, added to our knowledge of park natural or cultural resources, and publicized national parks and the lives of rangers and their families.

Wives into the Wilderness

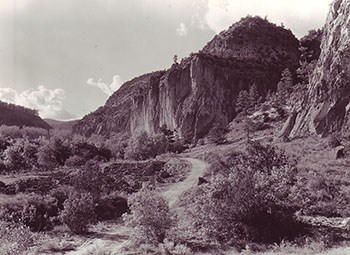

Although it was common for American women in the first 75 years of the 20th century to function as unofficial business partners for their husbands who received the credit (and the salary), doing so in the NPS often brought additional hardships such as isolation, primitive housing, lack of basic services for families, and even scary wildlife encounters. Unpaid and without the visible “green and gray” uniform, they nonetheless worked for, and in support of, the NPS in ways both large and small.

In its infancy, the NPS preferred to hire unmarried men as park rangers at remote places formerly managed by the military. Housing in parks like Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Sequoia was limited and consisted mostly of former US Army barracks for enlisted men with a small number of houses for officers and their families. When the NPS took over these parks, the facilities lent themselves to continuing this approach, which wasn’t always popular with employees. At Yellowstone, rumors of early rangers smuggling their wives into the park were recounted among employees for decades.

Even when wives were permitted, not all families could adapt to park conditions. In a September 24, 1923, letter to Assistant Director Arno B. Cammerer, Yellowstone Superintendent and NPS Assistant Director (Field) Horace M. Albright wrote “Any superintendent that moves out of his park in winter must expect considerable extra expense. It costs me a mighty lot to move my family over to California every winter, but I have to do it, or I could not stay in the game. On the other hand if the Service insisted I stay here all year round, I would have to quit, because my family cannot stand this place all year round.”

Romance in the Parks

As more women entered the workplace, it’s not surprising that “office romances” developed. Arguably, it was even more likely to happen in remote national parks where small social circles were the norm. In the first half of the 20th century, it was common for women to leave work after marriage. The NPS certainly lost many women employees “to cupid,” as one NPS newsletter put it. In fact, many early NPS women employees are largely known to us today only because the Park Service Bulletin mentions their resignations after marriage.

Dama Margaret Brown, the first woman employee at Grand Canyon, married Charles J. Smith in 1921, not long after transferring to the park from the Washington Office. Her appointment as a clerk was not supported by the superintendent or most Washington Office officials. The park was new, and housing was very limited. However, she earned the support of Cammerer, and he approved her transfer. In 1930, her book I Married A Ranger was published. Cammerer wrote the forward for it, where he paid “a tribute of admiration to women of the Service, both employees and wives of employees, who carry on faithfully and courageously under all circumstances.” Although it’s now dated (particularly in how it refers to Native Americans), Smith’s book documents her experiences as a woman working and living at Grand Canyon with some surprising details. For example, she writes of her Native American roommate, a woman named Thea, hired as a fire lookout in the early 1920s. The book and many articles she wrote about NPS life for popular magazines gave the public romantic ideas about living in national parks—and marrying park rangers.

Some women remained in their positions for several months after marriage. Lulu Hazelbaker, a clerk at Glacier National Park from 1921 to 1925, worked for six months after her marriage to Lewis L. Hill, the park’s road work supervisor. Glacier Clerk Hilda J. Lund resigned about a year after her marriage to the park’s assistant chief ranger, Earl F. Dissmore, in 1930.

Yellowstone’s employees often found spouses at work, although many also married locals from Gardiner or other Montana communities. Women like Anna Madsen Greer gave notice before resigning in 1929. Others like Miriam Horkan, a clerk in the chief ranger’s office in 1932, eloped with ranger Jack Aiton to the surprise of many. Yosemite’s information ranger James V. Lloyd arrived at the 1926 chief rangers’ conference with his new wife, Ethel May Foster Lloyd, who had been the private secretary of the park’s superintendent for four years.

Of course, parks weren’t the only place romances blossomed. Many of the women who worked in NPS offices also became park wives. For example, Mary Mathilda Wahl, secretary in the San Francisco Office, married Mount McKinley (now Denali) National Park’s Superintendent Harry J. Liek in 1933. Their honeymoon included a flight over Mt. McKinley. In 1939, they moved to Wind Cave National Park, where they stayed until his retirement in 1954.

After they transitioned from employees to park wives, many of the women become harder to find in the historical record. It’s safe to assume, however, that if their husbands remained in the NPS, they faced the challenges of frequent moves and life in remote areas. They no doubt also provided unacknowledged (and unpaid) work and support for the NPS.

Honorary Custodians Without Pay

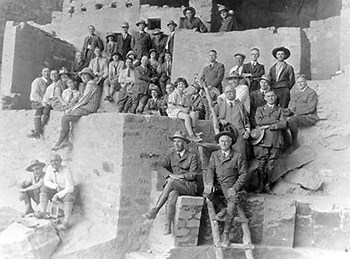

In spite of the challenges, women did live in the parks with their husbands either year round or seasonally. Many of the wives were well educated and just as qualified as their husbands. Southwestern National Monuments Superintendent Frank “Boss” Pinkley quickly understood what great assets park wives were, including his wife Edna. He did more than just acknowledge the wives with the affectionate (and unofficial) titles “honorary custodians without pay” (HCWP) and “honorary ranger without pay” (HRWP). He asked for their opinions on housing issues, insisted that they were part of their husbands’ transfer decisions, and gave them credit where credit was due in his monthly reports to Washington.

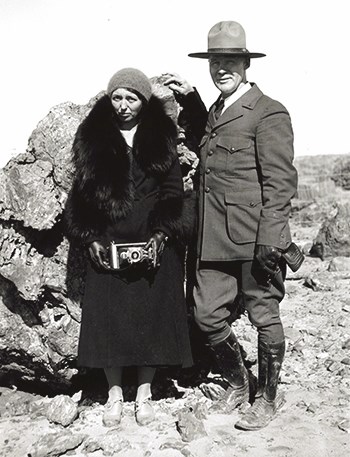

When Sallie Pierce Brewer, an NPS employee and archaeologist in her own right, married archeologist Jim Brewer in 1934, she joined him at Wupatki National Monument as an HCWP. Pinkley wrote at the time, “We think we’re doing well when we can angle for one archaeologist and get two!”

HCWP’s often provided tours, first aid, and sometimes even meals to park visitors, all without pay. At Wupatki National Monument, tours for visitors could last up to 2.5 hours each; in June 1942 alone, Courtney Jones donated over 33 hours of her time to that task. The HCWP at Saguaro spent more than 25 percent of her time in March 1948 in public contacts.

Wives also developed museums and interpretive materials, and some conducted natural history research. Betty Jackson at Montezuma Castle National Monument contributed to interpretive plans, developed bird lists, began a bird banding program, and wrote articles for the Southwestern National Monuments monthly reports. In his January 1939 monthly report, her husband Earl wrote, “Give me another five years and I will know as much about our birds as my wife.” She was also credited with archeological discoveries at Montezuma Castle and Bandelier national monuments.

The Struggle Is Real

Park wives and their families in the 1920s–1940s faced many challenges related to poor infrastructure in undeveloped parks and monuments. Even women who were used to difficult living conditions and were very successful in their roles as HCWPs struggled at times.

Educated at the Sorbonne in Paris, Aileen Nusbaum worked as a nurse outside of Paris during World War I. She and her son Deric returned to the United States after the war, and she married archeologist Jesse Nusbaum in 1920. She traveled across southern Utah by pack train and helped him excavate a Basket Maker cave site. She was clearly an intelligent, resourceful, and courageous woman. When she moved to Mesa Verde with him in 1921, they worked that first winter to build their home and most of their furniture. She also worked with him to design several new buildings for the park as well as their furnishings. Yet in September 1923, Albright wrote to Cammerer, “Mrs. Nusbaum’s case is serious. Of course, we have to do something for the Nusbaums. Why don’t you let Jess move down to Santa Fe for the winter? . . . We have simply got to keep the Nusbaums at all costs.”

Although we haven’t found her original letter that sparked these concerns, it likely referred to her extended isolation. Due to extreme weather, for a period of eight months she had no other human contacts besides her husband and son. As her situation improved, Aileen continued to make important contributions as an HCWP. She and Deric were actively involved in archeological excavations in the park. She played hostess to the Crown Prince and Princess of Sweden when they visited in 1926. Like Smith, she publicized the park, the NPS, and Native American traditions through her published writings. She also helped her son write Deric in Mesa Verde, his 1926 book about growing up in the park. In recognition of her work providing medical services in the park and local community, Congress provided funding in 1927 to construct and equip the Aileen Nusbaum Hospital at Mesa Verde.

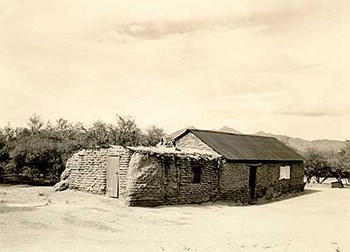

In addition to isolation, adequate housing was one of the most challenging aspects of living in early national parks. The Pinkleys lived in two tents with ramadas for years. When Congress wouldn’t appropriate funding, they resorted to paying out of their own pockets to build a decent house at Casa Grande.

Sallie and Jim Brewer began their married life at Wupatki National Monument. In August 1934 they were ready to move from their temporary quarters in a cook shack to a room in the pueblo. The monthly report noted, “Any member of the Park Service would grin and like the minor inconvenience of two walls, no roof, and scorpion and snake neighbors. . . Incidentally, this is probably the first time in 500 years that a young couple has spent a honeymoon in Wupatki pueblo.” During their marriage, the couple worked in eight Southwestern National Monuments. They lived in a pueblo, tents, a Navajo hogan, and a log cabin and even slept on the ground while living out of a pickup truck, before finally living in a traditional house the last two years.

Courtney “Cork” Jones and her husband Davy went to Wupatki after the Brewers and lived in the ancient pueblo for three years. Marge Peavey and her husband John lived in a tent for two years at Tonto National Monument.

Even when traditional housing became available, it was not luxurious—or even safe. Edgar and Gay Cook Rogers lived in various Southwestern National Monuments until he appointment as the first custodian at Bandelier National Monument. When they arrived in June 1932, they found a house with holes in the roof and standing water in two rooms, among other problems. Within a month, Edgar returned to Arkansas following his father’s death. Presumably, that left Gay to continue sorting out the house’s many issues. She also volunteered to lead tours in his absence. On July 30, 1932, Edgar wrote Pinkley that, “From what Gay writes, she makes a better ranger than I.” Indeed, she was so good at it that at the end of the summer, Albright, by then the NPS director, wrote her a letter praising her work.

Reliable supplies of water and electricity were also difficult to maintain in some remote locations. When these systems broke, repairs inevitably took days, if not weeks, forcing the wives to adapt to even more difficult situations. Houses large enough for growing families was also an issue. Custodian Frank L. Fish of Chiricahua National Monument noted in January 1937 that, “One bedroom with a wife and three children is a bit crowded but we are making out and so far no one has stuck there [sic] feet in my face. However, I intend asking the Branch of Plans and Design to consider a glass in the screen porch at the back to save the government buying me some new teeth when the babies get bigger.”

The December 1936 monthly report for El Morro National Monument shows just how difficult things could get. Custodian Robert Budlong described a harrowing situation he and his wife Betty dealt with when a promised government pickup truck didn’t arrive. They had no transportation as their own car was in a repair shop 45 miles way. “We anxiously awaited each mail day, hoping for word that the new pickup was awaiting us in Gallup. . . Our food supply gradually dwindled, and finally, when we received word on December 12 that the new pickup could not be delivered in Gallup until December 29, we found our food supply consisting of half a sack of flour and two cans of pineapple, plus some Christmas cookies.” Budlong was able to get a ride to his car but the repair failed, and it was three days before he got back to Betty with supplies. He noted that he “reached El Morro, to find that the HCWP had existed on Christmas cookies during my absence. We promptly celebrated the occasion by consuming a huge steak and a variety of fresh vegetables. I think the HCWP has lost her appetite for Christmas cookies for some time to come.”

The difficulties of living under these conditions took a toll on many of the women and their marriages. It’s perhaps not surprising that quite a few NPS marriages ended in divorce as a result.

When Tragedy Strikes

Park families sometimes had to persevere through the most devasting personal circumstances, made even worse by poor communication infrastructure, bad roads, and isolation. Long distances from doctors and medical facilities may be inconvenient for minor aches and pains, but they could also be fatal, as was the case for Edna Pinkley. The Pinkleys had lived at Casa Grande for 20 years when she suffered a cerebral hemorrhage and died at their home in the monument in November 1929. She was only 47 years old (see Women Who Were There). In 1939, Harry and Mary Liek transferred from Denali National Park to Wind Cave National Park less than a month before their 18-month-old daughter Mary Jane died. Although South Dakota was less remote than Alaska, to the bereaved parents new to the community and far from family and friends, it probably felt much more so.

Tragically, Edgar Rogers died by suicide at home in Bandelier National Monument on October 16, 1933. Successful in his home life and job, he was known to have “despondent streaks,” which at the time were not recognized as signs of a mental health issue. By chance, several NPS employees were able to be with Gay afterwards, arriving within the hour. She reached out first to fellow HCWP Dama Smith, sending her a wire asking her to come to her. The quickest she could get there was the next day, arriving by bus. The Smiths could only track down Pinkley, who was traveling between the monuments, by asking the police to watch out for his car. He also arrived the next day. They took Gay to Casa Grande National Monument until after the funeral and then returned with her to Bandelier the next day. When a new custodian arrived, she served as guide to help him become familiar with the monument.

Edgar Rogers’ suicide is one of the earliest recorded of an NPS official, but unfortunately it hasn’t been the last. Like much of our society, the NPS has often struggled to recognize people in crisis. Each death shatters families, friends, and colleagues. More than 85 years later, Edgar’s death and its impacts on his wife and colleagues still reverberate. At the time, the NPS rallied around Gay. In December 1933, she began working as a payroll and personnel clerk at the Southwestern National Monuments headquarters at Casa Grande. The following summer she was hired as a park ranger at Aztec Ruins National Monument. For three months, she and a male ranger conducted tours for visitors. The July 1934 monthly report for Bandelier noted “Gay Rogers dropped in for about an hour on the 17th, as exuberant as ever, and showing almost official dignity in her Park Service uniform.”

Creating Communities

Park wives didn’t just create homes in unusual places and structures. They also often created communities within parks and across the NPS. In addition to caring for their own families, these women cared for each other, organized dinners and other social events to combat isolation, and developed the broader concept of “the NPS family.” In 1940, women in the Southwestern National Monuments began their first newsletter to share their experiences and lend support to each other.

The arrival of wives in the parks often meant the arrival of children and the need for schooling. At many parks, wives like Hap Dodge homeschooled their children. Sometimes wives would pull together and create a school in the park, or children would attend existing local schools with the surrounding communities.

At Yellowstone, a school for NPS children was established in 1921. Grace Albright, wife of Superintendent Horace M. Albright, worked with NPS Director Stephen T. Mather to start it at Mammoth Hot Springs using donations. In the 1930s, parents operated the school using a school board model that billed families for sending their children to the school. Parents like Icel Wright and her husband Bill continued efforts to get permanent funding for the school, including writing to Congressman Burton K. Wheeler. After World War II, Montana Congressman Wesley A. D’Ewart introduced the Yellowstone Park School Bill. It was signed into law on June 7, 1948, as Public Law 504. The law allowed the secretary of the Interior to provide funds for the education of the children living within the park using revenue generated by park visitors. Superintendent Lon Garrison was successful in getting a new school building constructed as part of the NPS Mission 66 program. The Yellowstone school continued to operate until the end of the 2007–2008 school year, after which it closed due to declining student enrollment and budget concerns.

Wives also strengthened NPS relations with communities outside their parks. With book donations received from across the NPS, Betty Budlong developed and managed a community library at El Morro National Monument. By 1942, the library had 2,000 volumes. Ten schools and six other communities used the library. Of course, she did this in addition to her “usual” unpaid duties as a HCWP, which included guiding parties visiting the monument. In May 1937, she acted as an HRWP one day per week to cover tours during her husband’s absence. In December 1940, she even submitted the monument’s monthly report as her husband “has gone East on annual leave.” Left behind, Betty and a relief ranger managed a busy month in his absence. The comment inserted into the monthly report after her summary was “That's pretty fine, Betty! What do we need with a custodian when the custodian has a wife like YOU?”

The End of an Era

In February 1940, Pinkley organized a three-day field school for the Southwestern National Monuments custodians and their wives. Eighteen wives attended the training with their husbands, which was also the first time all the wives met as a group. After giving his opening remarks expressing that the event was “one of the red letter days of [his] life,” and before the applause had even faded, Pinkley sat down, had a heart attack, and died at age 58.

Pinkley’s death was the end of an era in the Southwestern National Monuments, and World War II soon brought change to women all around the country. In the NPS, more women and many wives stepped into positions left vacant by men fighting in the war. The wives at the Southwestern National Monuments, in particular, were well placed (and experienced) to do a wide range of duties that their husbands were no longer around to do.

After the war, the role of NPS wives changed. Although the NPS still found ways to use many of their organizational talents and professional skills in the 1950s, it no longer relied on the wives in the same ways. In the 1960s and 1970s, as more women went to work outside the home, the women themselves began to draw sharper lines around their roles, reminding new incoming wives that The Job is His, Not Yours.

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.

Tags

- aztec ruins national monument

- bandelier national monument

- casa grande ruins national monument

- denali national park & preserve

- el morro national monument

- glacier national park

- grand canyon national park

- mesa verde national park

- montezuma castle national monument

- sequoia & kings canyon national parks

- tonto national monument

- tumacácori national historical park

- wind cave national park

- wupatki national monument

- yellowstone national park

- yosemite national park

- nps history

- women's history

- nps careers

- uniforms

- hfc