Last updated: May 5, 2021

Article

The Job is His, Not Yours

In the early 1950s, park wives continued to function as they had from the 1920s to the 1940s. The NPS still got Two For the Price of One, relying on women to keep monuments in the Southwest running, to give freely of their time and talents, to build and maintain park communities, and to boost morale among park staffs. With the creation of the Mission 66 Program to improve park facilities, the NPS found new ways to put some park wives to (unpaid) work. As more women joined the workforce in the 1960s and 1970s, the role of park wives began to evolve. Although staffing increased in the late 1900s, available housing did not. As a result, more families lived outside parks, and employees commuted to work. These changes dramatically changed park communities across the NPS.

Getting Organized

Park wives had managed their homes, families, children’s education, and community relations within the NPS organizational structure for decades. They did so in difficult circumstances that often included abysmal housing conditions. It shouldn’t come as a real surprise, then, that when the NPS wanted to tackle its employee housing crisis, park wives spearheaded the charge.

The 1952 National Park Conference, held at Glacier National Park, was a turning point for park wives. In addition to their roles within their families and individual parks, some wives gained national roles. Herma Albertson Baggley recalled the moment at the conference when a “challenge was thrown out to the women that there was something they could do” about park housing. When architect John Cabot said something that “piqued us all, [we] decided to do something about it.”

At the conference, Baggley was elected chair of the newly formed NPS Women’s Organization. Over the course of the next year, the organization developed, documented, and compiled the results of the first systematic survey of existing employee housing. Women from almost every park responded to the survey, many providing photos of their living conditions in parks.

Baggley was “astounded” by what the survey uncovered. Even as someone who had lived in park housing since the late 1920s, had it not been for the photos, she wouldn’t have believed how bad it was. Some of the “low lights” of the report include 16.3 percent of residences didn’t have running water, 19.7 percent didn’t have sewers, and 15.2 percent didn’t have electricity. Those figures aren’t surprising considering they also documented the range of NPS housing in use. In addition to various two- or three-bedroom houses and apartments or duplexes, employees lived in 157 tents, 19 trailers, 256 dormitories or barracks, backcountry cabins, and even seven hogans. Almost half (42 percent) of these structures were over 20 years old. Forty-four percent of those surveyed considered their housing below the standards in the surrounding communities.

The Women’s Organization compiled their data and images into the 1953 Report of NPS Housing Survey. In it, the women asked for the American postwar housing standard of two- or three-bedroom, single-family, detached homes. They also advocated for housing to be built within the park itself, as it was hard to create the atmosphere of the NPS family when employees and families didn’t socialize with one another. Baggley and her team presented the report to NPS Director Conrad Wirth. It was later sent to the Bureau of Budget to document the need for substantial funding to address the crisis.

The internal reaction to the survey was positive and Baggley received many letters of thanks and congratulations from NPS employees. The superintendent of Grand Canyon National Park at the time wrote, “The National Park Service Housing Survey is a masterpiece!” It was also instrumental in helping the NPS get funding for Wirth’s Mission 66 plan to improve facilities throughout the NPS. Later the NPS Women’s Organization was told that the “report did more to influence the Bureau of the Budget as to housing conditions in the National park Service than any one thing that had ever been done.” No small feat!

Following the success of the housing survey, the women wanted to continue to make national change. At the 1955 National Park Conference held at Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Baggley asked the director if this was a worthwhile endeavor. He responded positively to the idea of continuing the Women’s Organization so that the women could “be ready at any time when there was a project they could do.” In practice, and in spite of its success, the NPS never gave the organization another project with the challenges and national scope of the housing survey.

Spreading the Word

After the success of the housing survey, NPS women recognized a broader need to share information and offer support to each other. They shortened their name to National Park Women (NPW) and sought to include both wives and NPS female employees. By the early 1960s, NPW had chapters in parks across the United States.

Building on the first newsletter for wives created by Sallie Pierce Brewer and others in the Southwestern National Monuments around 1939, local NPW chapters produced regional newsletters such as The Smoke Signal (Southwest Region) and Trailblazers (Rocky Mountain Region). The newsletters shared updates on personnel and projects, family announcements, short stories, and even recipes.

Most regions had a NPW newsletter in the 1970s. The Pacific Northwest Region’s The Breeze began in 1971 as a local newsletter but evolved in 1981 to encompass all NPS regions. It was published at least through 1986.

Women also featured in the official NPS newsletter, the National Park Courier, later renamed Courier: The National Park Service Newsletter. In the late 1960s, the newsletter ran a column dedicated to NPW news. Regular features also included a “See Here, Ladies” column and a “Silhouette” column spotlighting a wife of an employee or a woman employee. Due to a lack of submissions for the “Silhouette” column, it was replaced by a new “NPS Miss, Mrs., Ms.” Column. However, that feature only ran until February 1973. Today, the tone of many of these articles would be called condescending and sexist, but we don’t know how they were received at the time.

Between 1973 and 1984, there doesn’t appear to be a dedicated column for the NPW. Articles of “women’s interest” were still printed but not as a recurring column. The Courier added a NPW correspondent in January 1984, restarting a dedicated column again in February 1984. The column ceased after December 1986, when NPW appears to have merged with the NPS Employee & Alumni Association.

Tradition of Togetherness

Although some wives became involved in policy and national issues, most women continued to focus on their families, helping their husbands be successful in their jobs, and contributing to the morale in their parks. Throughout, wives still contended with geographic and social isolation, making homes in less than ideal structures, and frequent moves in support of their husbands’ careers.

Wives also continued to do the work of NPS employees without being paid—and usually without any formal training. In the late 1950s, while her husband was away from their ranger station at Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Annie Freeland made out camping and fire permits while nursing a baby. She is reported to have also killed a copperhead in her home with one shot. For decades, in many parks wives were “volunteered” to staff information desks and even serve as radio dispatchers, jobs that were paid elsewhere when done by employees.

In May 1975, the National Park Courier published an article written by park wives at Apostle Islands National Seashore that discussed the expectations and needs of a park wife. It noted that wives were expected to be friendly and smiling, not overbearing yet proud of the NPS, and willing to go to things alone yet open to making new friends. They advocated for briefing sessions on park issues to make them better able to attend to their duties as park wives, noting that they were expected to know just as much as their husbands but with no training.

Although the 1953 NPS Housing Report advocated for keeping housing within parks to support the NPS family dynamic, over time that became unsustainable. Today, in most parks, staffing levels exceed available housing and families often live in nearby towns and cities. Most employees commute home after the work day is done. Together with an increasingly temporary workforce, it can make the sense of community (and sometimes employee morale) harder to maintain within a park. Many large parks continue to have strong communities within individual housing areas, but often those who live in the parks represent a small percentage of the overall staff. Living in nearby communities, however, provides employees with more housing options, easier access to schools and other facilities, and opportunities for spouses to pursue their own careers and interests outside the NPS. Although relying on the private sector for housing outside of parks is a cost-effective approach that limits development within parks, it often takes a toll on the NPS tradition of togetherness.

Mrs. Assistant

Continuing the tradition of women like Virginia Harrington, Aileen Nusbaum, and Sallie Pierce Brewer in the 1930s and 1940s, many park wives functioned as research assistants, field technicians, and “girl Fridays” to their husbands for a wide variety of NPS projects.

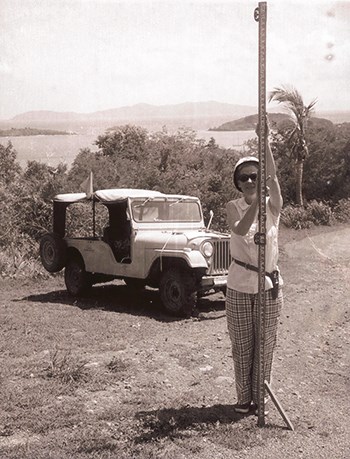

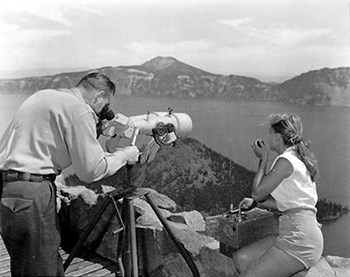

Mollie O’Kane’s husband Dave worked for the Western Office of Design and Construction. Between 1955 and 1973, the couple moved 45 times around the United States and its territories. In spite of the Mission 66 emphasis on improving park housing, the O’Kanes often had substandard accommodations. Starting in a tent at Yellowstone, Dave O’Kane recalled that they “worked up through dilapidated, old 8-foot trailers… shacks, mobile homes, commercial rentals, motels, and a three-bedroom, three story apartment at Crater Lake.” Mollie tried to make the most out of every housing situation, scrubbing dirty appliances, making do with what they were given, and doing whatever needed to be done to make a home wherever they were. In addition to being a homemaker, cook, and hostess, she was a Girl Scout leader, responded to wildlife emergencies such as a grizzly bear attack, acted as assistant librarian, and edited newsletters. She also assisted her husband in his work duties, like “running the level rod, typing reports, answering the phone, and generally running the office.” None of this earned her a paycheck.

Emma Guillet, wife of Meredith Guillet, custodian of Canyon de Chelly National Monument, served as the postmistress and even as deputy custodian when her husband was away in the 1940s. Betty Robertson was field assistant to her husband Bill at Fort Jefferson National Monument (now Dry Tortugas National Park). Dr. Bill, as he was affectionately known, began a research project on the sooty tern colony on Bush Key in the park in 1959. Over the next 40 years, Dr. Bill and Betty, together with assistants and student volunteers, banded more the 500,000 birds in the longest-running project of its kind.

A Knock at Night

Park wives responded to threats from wildlife, accidents, and medical emergencies on their own in isolated areas and often while filling in for their ranger husbands. The women also stepped in as unpaid radio dispatchers and fire spotters even as they worried about their husbands’ safety during backcountry rescues, firefighting, or other hazardous activities.

The women often received knocks on their doors from a host of characters. In park housing in a developed area, an after-hours knock usually meant someone was looking for a ranger. During the day, it likely meant tourists ignored the “authorized personnel only” signs at the entrance to the housing area because they wanted to know who lived there or what it was like to live in the park. Suffering through these invasions of privacy, park wives became unpaid guides on the spot. In remote cabins in the backcountry, the isolation made some women feel vulnerable and even fearful to open the door to strangers when they were home alone. Dealing with drunk visitors became a specialty of women like Margaret Merrill. In an interview, she recalled handling drunks and even escaped convicts with a “fresh coffee” while waiting for help to arrive. Merrill also put her first aid training to good use, creating an emergency room in the isolated ranger station in Yosemite National Park during WWII.

Drawing Lines

In the 1960s, the NPS began to professionalize many of the jobs that park wives had been doing without pay for decades. The women’s involvement in their husband’s jobs was no longer necessary to the NPS. In many ways, it became unwelcome.

In 1969, the NPW created an orientation booklet for park women that was approved by the NPS and shared across the country. In spite of claims that it was written as an open letter from “Mary Park Service” to both NPS wives and women employees, it is directed primarily at wives. Its stated purpose was to “help wives understand more about the National Park Service and what is involved in being a Park Service wife or employee.” Its opening greeting notes, “You are married to a very special man…”

It’s unclear how involved NPS managers were in the booklet’s content. As authors of the booklet, the wives began to draw lines between themselves and their husbands’ careers. They encouraged women to learn about the NPS and their husbands’ jobs, listen to them, and read everything they could about their husbands’ fields to avoid feeling left out. They also cautioned women not to “intrude on his official duties” as “the job is his, not yours.” This was a radical shift from the 1930s and 1940s when the NPS relied on the wives digging in with their husbands to help the parks operate.

The 24-page booklet provides guidance on a number of topics:

-

moving (“Each move is an opportunity for your husband, perhaps an advancement in his career.”)

-

housing (“Some floor plans present the new housewife with a real challenge.”)

-

shopping (“Learn to make lists.”)

-

getting along in the park community (“It is not fair for wives to burden husbands with complaints about a neighbor when he has to work with the same man all day.”)

Although park wives did not wear a uniform, the orientation booklet notes, “As a Park Service wife, it is your responsibility to see that his clothes are ready when needed, clean and neatly pressed.” It also reminded wives that their husband’s uniform allowance was to be spent appropriately, not on a "night out" or “a new pair of shoes for you.” Although the tone of some items was perhaps meant to be funny, that humor hasn’t aged well!

Fun-Raising

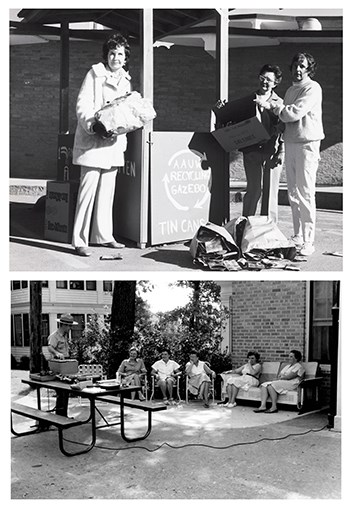

For decades, park wives organized fundraising activities for park needs and other charities, managed clothing drives and recycling events, organized “pot luck” dinners, and created projects that built community relationships for the NPS. In 1973, Elizabeth Hinsdale, wife of the chief of interpretation and resource management at Nez Perce National Historical Park, created an audio library for blind children in the community.

Popular fundraising projects organized by NPW chapters included publication of park cookbooks. NPS cookbooks not only shared favorite recipes but also gave helpful tips for living in remote parks where limited shopping opportunities often meant meals had to creatively conjured from whatever canned foods were left until the next trip into town. Recipes and tips were also included in NPW newsletters for similar reasons. Everglades and Rocky Mountain national parks are just two examples of parks where cookbooks were created, shared, and sold for charity in the 1970s. The Western Regional Office cookbook raised $11,000 for the NPS Employee & Alumni Association’s Educational Aid Fund. The Courier regularly printed articles about NPW activities and fundraisers.

In addition to providing financial benefits to worthy causes, these activities and many others created a sense of community within a park.

From NPS Wives to NPS Spouses

As more women joined the workforce in the 1980s and 1990s, the dynamics of “park women” began to change. Those hired by the NPS often became members of employee groups rather the NPW. Many spouses got paying jobs of their own, either for their own fulfilment or because families needed dual incomes. Either way, they had less time (and perhaps less interest) to do many of the tasks that traditionally fell to park wives.

Spouses and partners of superintendents, regional and associate directors, and NPS directors continue to unofficially represent the NPS. They function as hosts or ambassadors as they entertain NPS managers and staff, mingle with dignitaries, and attend special events. However, families at all levels of the NPS still face many of the same challenges of earlier generations.

Although more positions in urban parks, support offices, and regional offices offer more options for spousal careers, school choice, and local amenities, frequent moves for career advancement in the NPS often means that spouses’ careers suffer, or they cannot work in their chosen fields. Isolation from family and friends can still be felt keenly in remote parks and other areas where internet and cellular services are poor. In some areas, grocery stores and other services can require long car rides or even travel by boat or airplane.

Although they are not first responders, NPS spouses also deal with emergencies like fires, floods, tornadoes, and hurricanes as well. Disasters impact entire families and communities, not just employees. Spouses are often left to deal with the family preparation and response while employees protect park resources. In the aftermath of such events, families may be displaced from their homes, and again the spouses often shoulder a larger burden on the home front, including the emotional toll it takes on the entire family.

For putting up with so much, for giving so much, for supporting the careers of so many employees, and for furthering the NPS mission, we all owe NPS spouses and families a hearty THANK YOU!

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.