Last updated: March 8, 2025

Article

Triaging Invasive Plants: Strategic Planning Drives Success

A winning strategy to combat invasive plants becomes a potent tool for restoring special places in several eastern parks

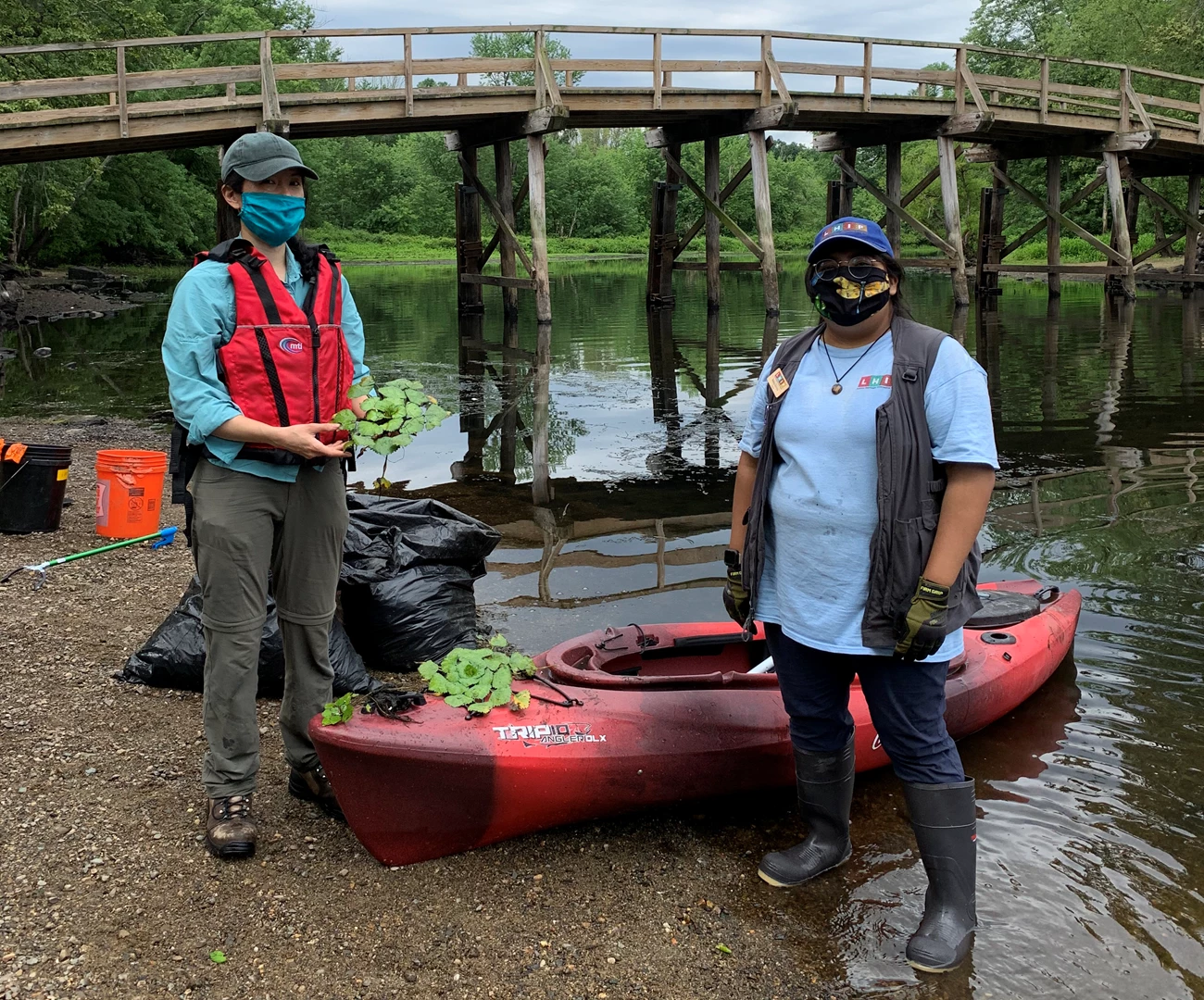

Image credit: NPS / Ada Fox

In Minute Man National Historical Park, glossy buckthorn trees blocked the view of historic stone walls where civilian military volunteers concealed themselves against the column of British soldiers.

Exotic bittersweet vines blanketed the forest edge, threatening to pull down trees that protect sensitive vernal ponds. These ponds are the wetlands that shaped the militia’s movements during the opening battle of the American Revolution. As the park’s resource manager, Margie Coffin Brown sees invasive plants every day and knows that the problem is getting worse. Visitors at Minute Man “anticipate learning more about the causes and consequences of the American Revolution within a historic landscape setting,” she said. “If that landscape is covered with invasive plants, it impairs the look and feel of the historic setting, as well as diminishing the ecological health of the landscape.”

An Intractable Problem

The problem with invasive plants is not that they originate outside North America. Many of the ornamentals we enjoy in our gardens are from other countries. Plants, native or not, are considered invasive when they spread in such abundance that they affect ecosystem function, reduce native biodiversity, and pose threats to the long-term health of ecosystems. But damage to natural and cultural resources aren’t the only issues. There are economic costs. Some researchers report a “strongly underestimated” cost of invasives worldwide of at least 1.3 trillion dollars in 1970–2017, with an average cost of 26.8 billion dollars each year. The presence of invasives also has recreational impacts, such as increased risk of Lyme disease for hikers and hunters.

Eastern national parks have forests that have more kinds of trees and older trees than the surrounding forests outside the parks. Eastern park forests, where logging is usually prohibited, also contain more large trees and more fallen logs than their non-park counterparts. This provides increasingly scarce habitat for many wildlife species. For the sake of both cultural and natural resources, protecting regional park forests like the one at Minute Man is important. Northeast Temperate Network Plant Ecologist Kate Miller and others recently found that invasive plants are increasing in 80 percent of the eastern parks they study. Yet the challenge of managing invasive plants can be so overwhelming that park staff are tempted to give up, because it seems like an unwinnable uphill battle. With limited time and resources, what can parks do to combat the spread of plants with well-deserved names like “mile-a-minute,” “foot-a-night,” and “burning bush”?

A Winning Strategy

Over the past decade, Art Gover at Pennsylvania State University created a strategic invasive plant management tool for Pennsylvania state park managers, who also grappled with overwhelming invasive plant problems. The tool was guided by a few basic principles:

- Parks have finite resources.

- We can use existing park-specific data on invasive plants to plan strategically.

- The key to successful invasive species management is to focus on the park’s most important sites.

- Inaction is more harmful than action. If we do nothing, the resources in our parks are in peril.

The Youghiogheny River Gorge in Ohiopyle State Park in southwestern Pennsylvania is a popular whitewater rafting destination and the site of many rare plants. But Japanese knotweed threatened this sensitive habitat and recreation area. Gover’s tool helped the state park focus its energies on the land around the gorge.

"Just because you can't see it from the trail doesn't mean it's not a priority."

In 2020–2021, several national parks, the Park Service's Inventory and Monitoring Division and Invasive Plant Management Teams (IPMTs) collaborated to create strategic treatment plans based on Gover’s tool. The tool helped identify the highest priority places and species within each park, so that parks could use their limited resources effectively. The collaboration was vital to their success.

Richmond National Battlefield Park Resource Manager Kristen Allen put it this way: “We put our heads together and used the data we had to prioritize important areas, which is what we were lacking before. You tend to treat the areas you can see, but just because you can’t see it from the trail doesn’t mean it’s not a priority.”

Doug Manning, a biologist at three national parks in West Virginia, agreed. New River Gorge National Park and Preserve, Gauley River National Recreation Area, and Bluestone National Scenic River together cover more than 90,000 acres. “Prioritizing where to treat invasive plants is extremely challenging given the available resources,” said Manning. “Working with our inventory and monitoring network to identify where areas of ecological importance and priority invasive plants overlap has allowed our parks to be more effective in protecting at-risk species and communities.”

Photo courtesy of Marie Pinto

A Familiar Platform

The planning tool itself is an EXCEL workbook. It’s not high tech, but it helps parks determine where best to focus their resources using readily available information. It integrates existing inventory and monitoring data, IPMT expertise, and park knowledge to identify the most ecologically and culturally important areas of the park. It directs park resources towards areas where it’s most important to manage invasives.

“The tool helped us realize that we were spending a lot of time at a roadside area that was not one of our highest priorities."

At Minute Man, strategic planning helped shift the management focus to areas around rivers and streams. These riparian areas are places where invasive species are likely to spread through the waterways to other parts of the park and surrounding properties if left untreated. “The tool is not only helping us decide where to work, it’s also helping us decide where NOT to work,” Margie Coffin Brown explained. “The tool helped us realize that we were spending a lot of time at a roadside area that was not one of our highest priorities. The plan helped us refine our approach and improve our efficiency.”

By focusing on the most ecologically and culturally important areas in parks and prescribing treatments that are attainable, the process helps parks achieve wins that protect their special places. The tool works because it encourages collaboration, combining park knowledge with inventory and monitoring data and IPMT expertise. “It was nice to have National Park Service staff from multiple disciplines looking at our forest data and helping us prioritize where we should be putting our effort,” said Allen.

Timing Is Everything

One of the biggest challenges with managing invasive plants is timing—having people with the right training and equipment at the right place during the right time of year to treat each species. A key outcome of the strategic planning process is specific treatment prescriptions, with details on when the treatments should be conducted. The process allows park managers to easily match available workers with needed tasks, year-round. Park managers can direct volunteers, Park Service staff, interns, and others to high priority sites to do work matched with their level of skills and training.

Image credit: NPS / Joseph Lyon

Portable Plans That Fit in Your Pocket

Using mobile mapping platforms, parks can take their treatment plans practically anywhere. The Eastern Rivers and Mountains Inventory and Monitoring Network built a digital map for the National Parks of Western Pennsylvania. It allows park staff to get information about priority treatments and invasive species locations when working outside.

Better Communication

Once Minute Man’s treatment plan was completed, Brown realized, “We now have a real communication tool to talk with our collaborators and convey to them our set of priorities. We have shared our plan with National Park Service staff, partner parks, adjacent landowners, and surrounding towns who have robust invasive plant management programs. It gives our invasive plant management program a higher level of credibility and more leverage. The plan has improved our conversations about where we are working and why.”

“We need to do a better job convincing people that invasive plant management is important, that when we focus on our priority areas, we can make a difference.”

Having a strategy also helps demonstrate to other Park Service divisions that invasive plant management is critical to protecting park resources. “We need to do a better job convincing people that invasive plant management is important, that when we focus on our priority areas, we can make a difference,” added Brown.

Image credit: NPS / Margie Brown

Smooth Transitions

An invasive species management strategy based on the Penn State tool can help ensure management priorities remain in effect during staff transitions. For new seasonal staff, the strategy can be incorporated into orientation and training, showing them how their work fits into protecting park resources. For supervisors, it provides concrete action items to roll into their staff’s annual work plans. “Once our biotech had the plan, he could just jump in and start treating some of the top priorities,” said Allen. “Everything was right in place—from which tools and herbicides to order, to where in the park to go.”

"All the native seeds are just waiting for a little more real estate. Removing the glossy buckthorn allowed the native seeds to germinate and flourish.”

Success Stories

Visitors to Minute Man can now see native bees and other pollinators visiting native plants in the areas where invasives once ruled, like the forest around the visitor center. Program Manager Margie Brown is excited that “we don’t have to do a lot of replanting. All the native seeds are just waiting for a little more real estate. Removing the glossy buckthorn allowed the native seeds to germinate and flourish.”

At Richmond National Battlefield Park in Virginia, a native oak-hickory forest now thrives along Totopotomy Creek. Prior to treatment, the creek area was a “nightmare” of invasives. Wisteria and bittersweet vines draped like curtains hanging off the trees. Japanese barberry, burning bush, and crepe myrtles ran rampant in the forest understory. The forest now has far fewer invasive plants, and those can be maintained with minimal effort. “I went to look for wisteria there the other day, and I couldn’t find it anywhere,” said Allen.

Download the tool and see completed park invasive species management plans in the National Park Service Data Store.

Stephanie Perles is the plant ecologist for the National Park Service’s Eastern Rivers and Mountains Inventory and Monitoring Network. She studies forests in national parks. She helps parks deal with invasive species, forest pests, and deer. She helps them understand how prescribed fire can sustain oak forests. Her favorite pastime on long trips is to make up haiku (very bad ones, according to her two kids). Photo credit: NPS / Stephanie Perles

Tags

- bluestone national scenic river

- gauley river national recreation area

- minute man national historical park

- new river gorge national park & preserve

- invasive

- plants

- invasives

- management

- mapping

- stephanie perles

- features

- ps v35 n1

- park science magazine

- resilient forest management

- park science journal

- stories by women authors