Last updated: March 12, 2022

Article

The Women Naturalists

Only two early women park rangers made the transition to park naturalists. Having resigned her permanent ranger position after her marriage, Marguerite Lindsley Arnold returned to Yellowstone National Park under the temporary park ranger (naturalist) title from 1929 to 1931. Yosemite rehired Ranger Enid Michael as temporary naturalist each summer from 1928 to 1942. A handful of other parks hired a few new women under the newly created ranger-naturalist designation.

The Doctor Is In

Dr. Margaret Fuller Boos got the temporary ranger-naturalist position at Rocky Mountain National Park that Ruth Ashton had wanted. She has hired for the 1928 and 1929 seasons, even though Superintendent Roger W. Toll stated that he “should prefer a man for the work.” Fuller Boos was the first woman hired in the NPS with a PhD. Interestingly, it wasn’t her doctorate in geology that convinced him to hire her. Although he acknowledged her successful teaching credentials, her valuable lantern slide collection (and his desire to have her make some for the park) seemed to be her overriding qualification in his eyes.

As the first woman ranger-naturalist at Rocky Mountain, Fuller Boos gave evening lectures to thousands of visitors, led visitors on field trips (some of which lasted all day), and wrote 20 articles for the park’s Nature Notes newsletter. At the end of the 1929 season, she was offered a permanent naturalist position at the park. While we’d like to say that her competence in the position changed Toll’s mind about women naturalists, the truth is that he transferred to Yellowstone National Park in February 1929 before the offer was made. Fuller Boos turned down the permanent job and instead developed a successful career as a highly respected geologist outside of the NPS.

From Pillow Puncher to Park Naturalist

Ironically, Superintendent Toll found that he had another woman naturalist to contend with at Yellowstone. Herma Albertson worked in the park beginning in 1926, after receiving a BS in Botany. She later recalled that “Mr. Albright had said that if I was willing to work as a naturalist but not have the rating of a naturalist nor the title of naturalist, live at the Old Faithful cabins and be a pillow puncher for my room and board, as there was no place for a woman to live other than that, and work for the Government in the afternoon, they would like to try me out. And that’s what I did.” In 1926, she spent her mornings as a maid (“pillow puncher”) at Old Faithful, working for the Yellowstone Parks Camp Company and earning $15 per month and room and board. In 1927, the park found her accommodations in the “puphouse,” an old Army cabin. She lived there and ate with the park rangers and no longer needed the second job.

Although his original intent may have been to hire her as an NPS employee after an initial “try out,” by 1927 policies aimed at Protecting the Ranger Image likely made that imprudent or even impossible. She returned to the park for the summer of 1927 but continued her laborer status. She is listed on the park employee roster that year as “without appointment.”

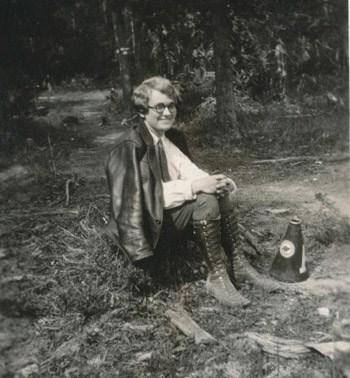

As a laborer from 1926 to 1928, each summer Albertson worked with others to develop the Nature Trail at Old Faithful. She created signage and led tours as well. She didn’t wear the standard uniform, but her breeches, shirt, tie, and boots are reminiscent of the prescribed temporary ranger uniform worn before 1923.

In 1928, the new classification of park ranger-naturalist was created. Albright could now hire her as an employee. She later recalled, “One day Mr. Albright and Director Mather…sent for me to come up to the camp’s office. Of course, I went with fear and trembling, because I was sure I had done something I shouldn’t do. Mr. Albright asked me then if I would come the next summer and be stationed at Mammoth” as a temporary ranger-naturalist.

In a 1978 oral history, Albright doesn’t discuss the day laborer arrangement with Albertson. Instead, he mentions only that she had been working at the Old Faithful Lodge when she approached him for a job. As he recalled it, “I said, ‘Why not?’ And I had her appointed.” After three years of working in the park, on June 16, 1929 she received an official appointment as a temporary park ranger naturalist.

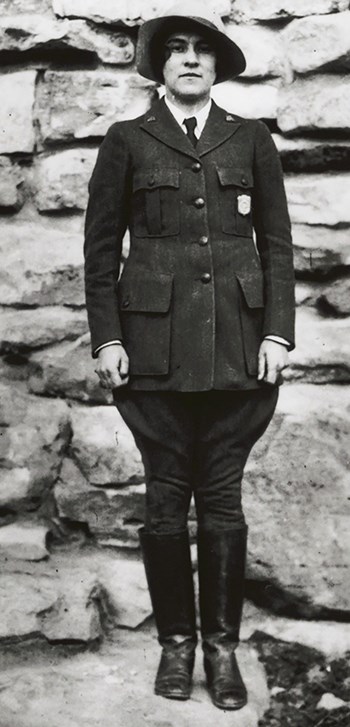

She continued with temporary appointments each year until 1931. Her temporary naturalist position in 1931 was converted to that of junior park naturalist on May 8, 1931 after she passed the naturalist Civil Service exam—with the highest test score in the country that year. With that appointment, she became the first permanent women naturalist in the NPS. A June 30, 1931, newspaper article noted, “Wearing the uniform, of which she was distinctly proud, created quite a stir among some women visitors at the park.” Albertson is quoted, “Women often sympathized with me or pitied me, though why they should always mystified me.”

As a permanent naturalist, she began working year round. In spite of her qualifications, Superintendent Toll began to use her more as a secretary in the winter than as a naturalist. This attitude earned him a rebuke from NPS Director Horace M. Albright when he learned of it.

In 1929 Albertson married George Baggley, the park’s chief ranger. She continued to work as a naturalist until she resigned her position “to become a full-time homemaker” on December 31, 1933. Like so many other women who married NPS men, she continued to offer her expertise and services to bureau--she just no longer got paid for it.

Polly’s Panache

The first woman ranger-naturalist at Grand Canyon National Park was Pauline “Polly” Mead. A talented botanist, she had studied plants in southern Utah before focusing her master’s degree research on the plants of the Grand Canyon. Turned down by the Forest Service because she was a woman, she came to the NPS instead.

Mead recalled in a 1978 oral history that she started at the park in 1929 but her official personnel record lists 1930 as her start date. It is possible that, like Herma Albertson, she was hired as a day laborer. She was still pursuing her master's degree that year and was in park conducting field work that summer.

Mead wore the standard NPS uniform including breeches, coat, riding boots, and badge. Although different, her hat was approved by the superintendent as an exception to the standard uniform, per his discretion in the uniform regulations. He preferred she wear a style similar to that worn by women tour guides for Fred Harvey’s Indian Detours. She recalled, "I got one of those hats and put a Park Service [hat] band on it, sort of soft leather."

There are a handful of known photographs of Mead conducting public tours at Grand Canyon. In all of them, she wears her uniform, as expected. However, there are three other photos of Mead that we admit we’re at something of a loss to explain. What she’s wearing in them is . . . well, unique.

In the photos, Mead wears white breeches, white shirt, riding boots, tie, badge, a vest (which appears to be a coat with the arms ripped off), and a felted or knitted hat. This is clearly not the standard NPS uniform or what she wore when doing official naturalist duties. The three images are dated 1929, 1930, and 1931.

The 1929 image lends support to her earlier start date. In 1978 she recalled, "I had a uniform like the men, but right at first I just wore a sort of riding habit." The fact that she was still wearing the outfit in 1931 indicates it was more than just a "starter" uniform, as it were.

The fact that she is wearing her ranger badge makes it look “official,” but is it? In one photo, Mead stands next to her sister Catherine, who stopped at the park on her way to Europe in September 1930. Most NPS employees have given family and friends private tours but rarely with such style, shall we say. The fact that both sisters are dressed in white breeches and shirts might be a clue as to their activities, but without further information we can’t say what those were for sure. While we can’t explain her outfit, if she was on her own time, it’s her business, right?

Maybe, but there’s another photo to consider. It was taken at the Yavapai observation station in 1931. Mead—in her signature look—kneels in front of a group of rangers while planting a memorial tree following NPS Director Mather’s death. This certainly looks like an official activity, given all the men in uniform around her. Indeed, the man kneeling next to her is Assistant Superintendent Preston P. Patraw, which lends an air of acceptance to what she is wearing.

In the photo, as the botanist, she was the one down on her knees actually planting the tree. We’ve also seen another photo of her wearing the same outfit while collecting plants in the park. It’s reasonable to assume that this outfit was something she wore to stay cool and to keep her uniform clean while doing outdoor work that didn’t require contact with park visitors. We may never know exactly what was behind “Polly’s panache” but, given that she wore it over three years, it is safe to say that her supervisors didn’t take issue with it.

Mead married Assistant Superintendent Preston P. Patraw in May 1931 and, once again, the NPS got Two for the Price of One. In a 1978 interview, former NPS Director Horace M. Albright recalled his thoughts behind the decision to appoint Preston “Pat” Patraw as superintendent at Zion National Park in 1932. It was Polly’s knowledge of Zion’s resources that led him to select her husband. He remembered, “They made a lot of fun of me for a long time, that the director was really for Polly, not Pat.”

After Mead left Grand Canyon in 1931, there wasn’t another woman naturalist there until Elizabeth Ann Livesay took a seasonal naturalist position in June 1949.

A Career of Seasons

Like Enid Michael at Yosemite National Park, Mildred Ericson had a long NPS career without getting a permanent naturalist position. A 1939 graduate of the Yosemite Field School of Natural History, she developed the nature guide service for the Minnesota state parks under the Works Progress Administration in the early 1940s.

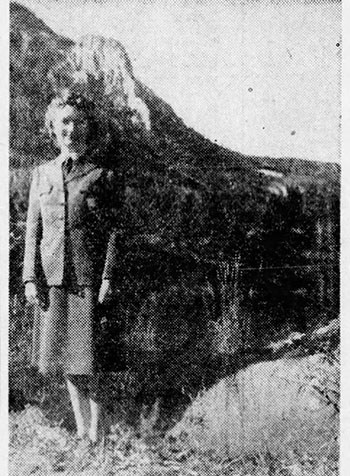

In 1945 as World War II was drawing to an end, she became a guide at the National Capital Parks, leading nature walks. The next year, she finally got a naturalist position at Yellowstone National Park. One published photo suggests that she wore the separate women’s uniform created in 1947 with its skirt, in spite of the outdoor nature of her work. That same article describes her as “the only female park naturalist in the West.”

Ericson continued working at Yellowstone for 20 summers. During the rest of the year, she taught biology and wrote articles on natural history topics that were published in a variety of magazines.

A 1949 newspaper article about Ericson refers to her as “one of the few women ranger-naturalists” at that time. Certainly, there were a few more women who managed to get naturalist positions at parks in the 1950s but, by and large, park naturalist jobs—especially permanent ones—went to the men. She remained the only woman in uniform at the park until October 1959.

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.

This research was made possible in part by a grant from the National Park Foundation.