Last updated: May 4, 2021

Article

The Unisex Uniform

R. Bryce Workman’s book National Park Service Uniforms: Breeches, Blouses, and Skirt 1918-1991, published by the NPS in 1998, has been the go-to resource for the history of women’s uniforms. Although it contains much useful information and photographic documentation, some of his assumptions must be challenged if we are to fully understand how the uniform reflects women’s history in the NPS.

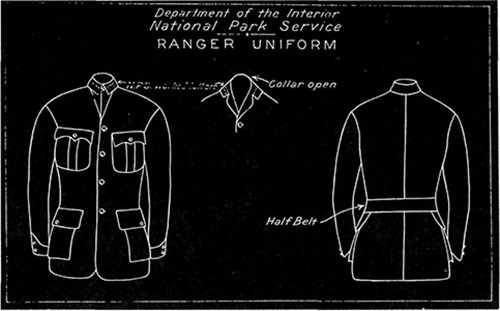

The NPS approved its first official uniform on March 20, 1920, publishing it as the Regulations Governing the Use of the National Park Service Uniform by Officers and Rangers of the National Park Service. These first regulations are remarkably neutral, referring to officers, permanent rangers, and temporary rangers by position rather than employee gender. Male pronouns appear beginning in 1923 as regulations were updated. Of course, the choice of pronouns at that time doesn’t necessarily indicate whether women did or did not wear the uniform. The increasing use of male references over time is also not surprising given the small number of women rangers and officers in the early decades of the NPS.

Although the early regulations don’t specifically reference women, other evidence supports the position that NPS uniform regulations applied to both men and women in uniformed positions. Although much of the early photographic evidence has been misunderstood and is open to interpretation, a memo in NPS records at the National Archives provides needed clarity.

On December 13, 1926, Acting Director Arno B. Cammerer wrote to Mount Rainier National Park Superintendent O.A. Tomlinson. His comments on women and the uniform regulations were prompted by some on the uniform committee by suggesting that women in field positions be made exempt from the regulations. Asking that question is an indication that they were not exempt at that time and that women rangers were, in fact, covered by existing uniform regulations. Cammerer responded that women weren’t exempt, stating, “This has not been done heretofore but has been left to the discretion of the superintendents to specify what exemption should be made.” Exemptions include approving alternatives to the standard uniform (to adapt to local climates, for example) or even choosing not to have an employee in a given position wear a uniform at all.

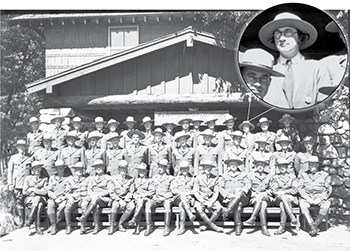

The timing of Cammerer’s memo is particularly significant as it comes less than four months after an official visit to Yellowstone National Park by two Department of the Interior (DOI) inspectors. In their report, they recommend against continuing to hire women rangers. Protecting the Ranger Image from women suddenly became important—even though in 1926 there were only three women rangers at Yosemite, none of whom wore the uniform, and five at Yellowstone who did. In 1927, the NPS and DOI decide against hiring more women “until a designation other than ‘ranger’ could be found.”

It’s probably not coincidental that new draft uniform regulations drawn up in 1927 explicitly mention women for the first time. However, rather than disenfranchising women from the ranger uniform as one might expect given the political climate, it stated, “Female appointees may, in the discretion of the Director, or the Superintendent, be required to wear the uniform prescribed for other departmental appointees.” For the first time, it also suggested that there could be accommodations for women in the design of the uniform, noting “when so required the type of uniform shall be as nearly as practicable [to] that specified.” This last sentence was probably a nod to the modified uniform coats approved in 1926 by Superintendent Horace M. Albright and Director Stephen T. Mather for Yellowstone’s Marguerite Lindsley and Frances Pound, respectively. It may also foreshadow the introduction of a uniform skirt for some women in the 1930s.

Tailoring a “Men’s Uniform”

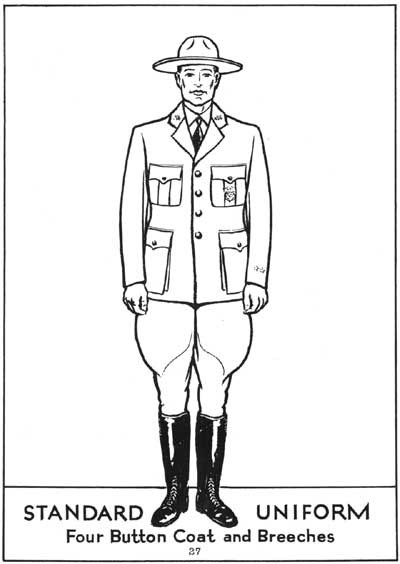

The language specific to women didn’t make it into the final uniform regulations approved in 1928. Instead, it included a new statement echoing Cammerer’s 1926 assertion that superintendents and the NPS director could decide which positions wore uniforms. For the first time, a sketch depicting a man dressed as a ranger was added to the 1928 uniform drawings. Earlier drawings simply showed the design patterns for the uniform. The sketch, which appeared on the approved design drawing, also appears on the Fechheimer Brothers Company’s NPS uniform order forms from 1928 to 1941.

Two other significant events also happened in 1928. First, the conference of national park officials established a standing uniform committee to recommend changes to the regulations as needed. Second, the Civil Service reclassified ranger positions, creating distinctions between park rangers, ranger-naturalists, and ranger-checkers (What Did You Call Me?). This provided the NPS a way around hiring most women as park rangers, using the ranger-naturalist and ranger-checker titles instead in most cases. At their superintendents’ discretion, women rangers and ranger-naturalists at parks like Grand Canyon, Yellowstone, and Yosemite continued to wear the standard uniform in the late 1920s and early 1930s. As with the earlier women park rangers, the number of women naturalists and checkers remained small.

Although some women begin wearing skirts as part of the standard uniform in the 1930s, skirts (and women) aren’t mentioned in any surviving uniform regulations from that period (Who Wears the Pants Around Here?). By 1940, when drawings are added to the uniform regulations themselves for the first time, the sketches depicted only men—further entrenching the idea that it was only for men even as it continued to be called the “standard uniform.”

Myth Busting

Although Workman didn’t create the myth of the men’s uniform, he did a lot to promote it, albeit with the best of intentions. His writing transformed the gender-neutral “standard uniform” for officers and rangers described in the regulations into the “men’s uniform.” For example, he describes Frieda B. Nelson as wearing the “standard men’s uniform, cut for a woman” in 1925. He also calls Herma Albertson’s 1929 uniform “the complete male-style Park Service uniform.” Although Workman isn’t the only writer to equate the early uniform only with men, his uniform series (published by the NPS) arguably has had the largest impact on how people today view the relationship between NPS women and the uniform.

Because women weren’t mentioned explicitly, and given the increasingly overt references to men in the regulations, it’s perhaps not surprising that he and others determined that NPS women didn’t have an official uniform until a separate one was created. Assumptions that women would naturally have been treated differently in the 1920s, coupled with a confusing array of historic photographs and the reality that men did fill most (but not all) officer and ranger positions at the time, no doubt also contributed to that misunderstanding.

In trying to make sense of available photographs, some of which admittedly appear contradictory at first glance, Workman concluded that, “Due to the lack of official guidance, early Park Service women wore whatever the park superintendent or their own whim dictated.” Yet, as we have seen, official guidance did exist at both the national level (regulations) and park level (superintendent discretion).

Arguably, Workman’s conclusions are the result of his chronological approach, which makes it harder to see patterns that existed by park. Beginning as he does with Clare Marie Hodges, it’s easy to see her as The Odd “Man” Out. Yet, put into park context, even she fits into the broader pattern of the women rangers at Yosemite National Park. In keeping with the superintendent’s preference, those women rangers didn’t wear the NPS uniform but, rather, relied on The Authority of the Badge. In contrast, Yellowstone National Park had “Girls” in Uniform during the 1920s.

Workman’s conclusion that early women rangers attached badges to any “clothing that struck their fancy” and that they “were left, pretty much, to their own devices as what they were to wear” doesn’t acknowledge that superintendents’ discretion was, in fact, part of the uniform regulations and accepted NPS practice. Moreover, it doesn’t account for the differences between temporary and permanent rangers until 1923 or reflect the struggles of the NPS in the 1920s to standardize the appearance of all the new bureau’s rangers.

Workman celebrated creation of a separate women’s uniform as a sign that “the National Park Service, at last, was recognizing women.” Yet, by not considering that the standard NPS uniform was not just the men’s uniform sometimes worn by women, he misses the important history of how most women were deliberately disenfranchised from uniformed positions in the late 1920s and early 1930s, with long-lasting results.

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.