Last updated: May 4, 2021

Article

The Odd “Man” Out?

Studies of NPS women’s uniforms often begin in 1918 with Clare Marie Hodges—and the statement (accepted as fact) that she didn’t wear a uniform. But which uniform are they referring to? While it’s true that Hodges didn’t wear the iconic green-and-gray uniform we know today, her clothes do reflect the accepted “riding uniform” worn by most early park rangers.

The Wild West of Uniforms

When Hodges was a ranger in 1918, an official uniform was under consideration, but nothing was settled. Uniforms were authorized beginning in 1911, but most rangers weren’t required to wear them. Uniform designs changed in 1912, 1914, and 1917. There was little consistency between parks—and sometimes even within a park.

In general, even rangers who wore these early uniforms only did so around park headquarters in the summer tourist season. The rest of the year they patrolled in “plain clothes” as it made it easier to catch lawbreakers in the act.

The NPS Riding Uniform

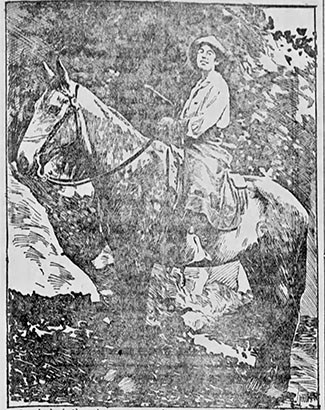

Reviewing photographs of Hodges in his 1998 book National Park Service Uniforms: Breeches, Blouses, and Skirts, 1918-1991, R. Bryce Workman notes, “She appears to have worn what was referred to at the time as ‘camping clothes.’ There are no pieces of regulation uniform evident, except for a badge or perhaps her hat.” In fact, her “ride astride” split skirt, long-sleeved shirt, kerchief gathered at the neck, leather gauntlets (gloves), and wide-brimmed hat are better described as riding clothes. A September 1918 newspaper article described her clothing as a “khaki riding habit,” but the accuracy of that color can’t be verified.

So, did her riding outfit make her the odd “man” out?

No, it didn’t! The rangers who came before Hodges and many of her contemporaries wore similar riding clothes (minus the split skirt, of course). Before the standard NPS uniform was required in 1920, a hat, coat, shirt, riding breeches, and shoes or boots were worn. Official status was denoted by The Authority of the Badge.

Although early riding clothes perhaps didn’t constitute an officially designated uniform, the same basic pieces of clothing were worn out of necessity. Although not official, it was certainly an accepted NPS “riding uniform” worn by permanent rangers before 1920 and temporary rangers until 1923.

In his book Guardians of the Yosemite, former ranger John W. Bingaman recalled Hodges, noting “Visitors were quite surprised to see a lady ranger with badge and full riding uniform.” In 1961, John W. Henneberger, then superintendent at Scott’s Bluff National Monument, responded to an NPS request for information about the history of women’s uniforms. He noted that Hodges “wore a full mounted uniform with badge.” These descriptions, together with photos of early men rangers, support the argument that what she wore was part of the long tradition of riding clothes worn by rangers because they were practical and durable for horse riding and outdoor work.

A Temporary Ranger

Although uniforms were in flux, some superintendents did outfit their ranger force in uniforms. Yosemite National Park Superintendent W.B. Lewis did so in 1917. However, only permanent rangers were uniformed at that time. The few photos that exist of Hodges consistently depict her wearing her badge on her riding uniform and reasonably suggest that she didn’t wear that 1917 uniform.

Only one known photo shows Hodges in the company of other rangers. Because the names and careers of the others in the image are known, it can be said definitively that Hodges was the only temporary ranger present. This, rather than her gender, is the simplest explanation for the differences between what she and the men wore.

The photograph is undated; due to Hodges’ appearance, it is assumed to date from May to September 1918. However, she remained at Yosemite for many years after her season as a ranger and, therefore, it could also date after March 1919 (when James V. Lloyd returned from service in World War I). Even if that’s the case, it doesn’t alter the interpretation of her riding uniform as appropriate for Hodge’s temporary ranger status.

A Lady Ranger

A “lady ranger” may have been unusual in 1918, but there is little to support the idea that Hodges’ clothing was unusual for the job she had, where she did it, and when. In fact, it was the diverse appearance of the riding uniforms worn by men that led the NPS to adopt its first official uniform, creating the iconic park ranger look in the process.

Without this historical context, it’s easy to see why Workman explained away her clothing as less meaningful than that of the men. In his 1994 book Park Service Uniforms: In Search of an Identity, 1872-1920 Workman stated, “From the photographs and lack of data to the contrary, it would appear that there were no uniform guidelines for female employees of the Service.” He further entrenched this idea in Breeches, Blouses, and Skirts by interpreting her “camping clothes” in isolation and with the assumption that “a uniform was not specified for women”. Arguably, he saw what he expected to see.

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.