Last updated: May 4, 2021

Article

The Authority of the Badge

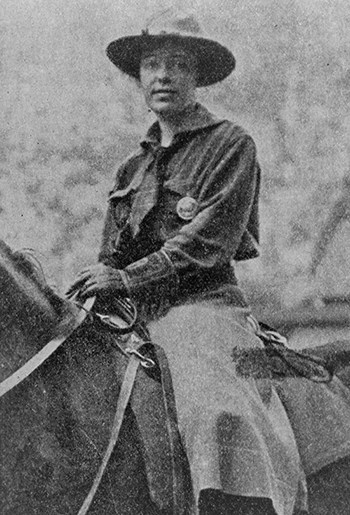

Following the success of Clare Marie Hodges as the first women ranger in 1918, Yosemite National Park hired at least five more women rangers in the 1920s. Using his discretion as superintendent, W.B. Lewis didn’t designate them as uniformed positions. His reasons are unknown. It could be that he didn’t support women wearing uniforms. Given that he hired the women rangers, however, he should perhaps be given the benefit of the doubt on that issue until proven otherwise. It could be that he didn’t think it worth the out-of-pocket expense for women as seasons were short and they were unlikely to become permanent rangers. Weighed together, perhaps he thought uniforms were unnecessary because the women were issued ranger badges.

“If You’re the Police, Where Are Your Badges?”

So asks Humphry Bogart’s character in the 1948 classic film The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. Although actor Alfonso Bedoya’s response is probably one of the most misquoted movie lines in American cinema, the exchange highlights the tradition and importance of a badge as the symbol of legal authority. In his 1991 book National Park Service Uniforms: Badges and Insignia, 1894-1991, R. Bryce Workman notes that before there were NPS uniforms, “badges were all that identified rangers.”

Yosemite, in particular, has a history of preferring the badge over a uniform. In response to the first suggestion of a standard ranger uniform in 1907, the park’s superintendent, Major Harry Coupland Benson, was the only one to disagree with the idea. He felt that it was better for rangers to be as inconspicuous as possible, noting, “They have badges under their coats which they can show in case they need to make arrests, seize guns, etc.”

Although the idea was popular in other parks, in 1908 the Department of the Interior decided against issuing a uniform, stating, “The National Park Service badge furnished by this Department is sufficient means of distinction of National Park Service employees.” In 1920, the NPS issued both its first official ranger uniform and its own ranger badge.

Emblems of Authority

In spite of the significance of the badge to park rangers, the government, and even lawbreakers, in his 1998 book National Park Service Uniforms: Breeches, Blouses, and Skirts, 1918-1991, Workman describes the badges worn by Yosemite’s temporary women rangers as signs of their “Park Service affiliation,” rather than their authority as rangers.

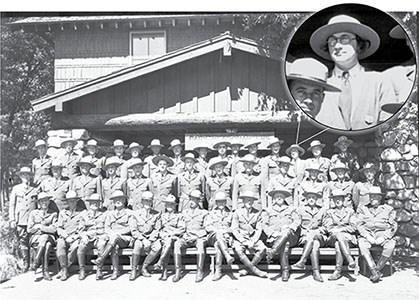

Although hiring Yosemite’s temporary women rangers was mostly A Family Affair in the 1920s, the fact that they wore badges instead of uniforms doesn’t suggest that they had less authority than their male counterparts. At the time, NPS regulations allowed only permanent and temporary rangers to wear the “U.S. Park Ranger” badge. Simply put, had these women been considered less than full rangers, they would not have been issued badges.

When asked about the reaction of men who saw her working at Yosemite’s ranger stations in 1926–1927, Ranger Eva McNally said, “Well, at first, I think they were quite surprised because I wore my badge. . . I don’t remember them objecting too much. I guess I could talk a pretty good story. They accepted me.” They also accepted the authority of the badge she wore. Then, as now, the badge was a significant symbol to the NPS, to park visitors, and to the employees like Yosemite’s women rangers who wore it.

In 1928, the Civil Service reclassified park rangers into three types: park rangers, ranger-naturalists, and ranger-checkers. Acting NPS Director Arno B. Cammerer noted that all three classifications were “empowered to make arrests for violations of park [regulations] and as the badge is an emblem of this authority all such employees should wear the badge.”

Also in 1928, Superintendent W. B. Lewis left Yosemite. With his departure, at least one woman ranger, Mrs. Hazel Whedon, did wear the uniform in 1931. Although the photo doesn’t reveal if she is wearing breeches or a skirt, she is wearing most of the standard uniform (including a badge). However, instead of the uniform coat, she appears to be wearing a cardigan sweater, which suggests that Superintendent Charles Thompson approved an exemption to the uniform regulations for her to wear it. In 1969, Whedon reported that as a woman ranger she had been “responsible for morals and sanitation.”

Explore More!

To learn more about Women and the NPS Uniform, visit Dressing the Part: A Portfolio of Women's History in the NPS.