Last updated: July 30, 2021

Article

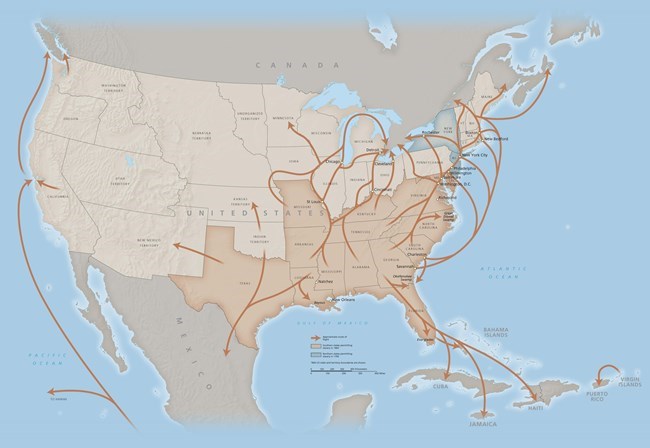

Places of the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a covert and sometimes informal network of routes, safehouses, and resources spread across the country that was used by enslaved African Americans to gain their freedom. This effort was often spontaneous, with enslaved people beginning their journey to freedom unaided. Many freedom seekers completed their self-emancipation without assistance. In the 1820s and 1830s, the United States saw an increased effort to assist freedom seekers. This gave the impression that there was an organized “underground” network. In some cases, the decision to assist a freedom seeker may have been a spontaneous reaction. In other instances, particularly after the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, the Underground Railroad was deliberate and organized.

Origins of the Underground Railroad

Enslaved people have always sought freedom, even in the earliest days of slavery. Colonial North America – including Canada and northern states in the US – was deeply involved in the slave trade. Newly enslaved Africans often ran away in groups intending to establish new communities in remote areas. Slavery also proliferated in northern states, making escape difficult. Before the mid-1800s, Spanish Florida and Mexico were the favored destinations for many escaping bondage. It was not until the northern states and Canada adopted emancipation laws that they became safer destinations for freedom seekers.

After Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, Canada became a haven for many attempting to obtain their freedom. This act made it both possible and profitable to hire slave catchers to find and arrest freedom seekers. This was a disaster for free Black communities in the North. Slave catchers often kidnapped African Americans who were actually legally free people.

But these seizures and kidnappings persuaded many more people to offer aid as part of the Underground Railroad. Individuals, couples, and even families participated in the Underground Railroad. Formerly enslaved men and women also played a significant role in aiding freedom seekers, such as the Clemens family. James and Sophia Clemens established the Greenville community in western Ohio. In addition to founding a school and a cemetery, they used their home as a stop on the Underground Railroad. Greenville even became a final stop for a number of freedom seekers.

The Role of Women in the Underground Railroad

Many women were active in the Underground Railroad. One of the most famous conductors on the Underground Railroad, Harriet Tubman made over a dozen trips into slaveholding states to guide enslaved people to freedom. While Tubman had many hiding locations, oral histories indicate that she frequently stopped at the Bethel AME Church in Greenwich Township, New Jersey. Located in the heart of the Black community of Springtown, the church offered lodging to freedom seekers travelling north after leaving Maryland's Eastern Shore and Delaware. Tubman used the Springtown station from 1849-1853. This route north through Delaware was one of her most famous.

White women, such as the Jacksons, also played a critical role in offering aid to freedom seekers. Living in Massachusetts, Mary Jackson and her family offered their homestead as a safe haven for those escaping along the Underground Railroad. Her daughter Ellen recorded some of their activity, writing that "the Homestead's doors stood ever open with a welcome to any of the workers against slavery for as often and as long as suited their convenience or pleasure.” After Mary’s husband William died in 1855, she and her daughters continued to play a role in the life of the community. In 1865, Ellen helped found the Freedman's Aid Society in Newton. She served as its president until her death in 1902.

The end of the Civil War brought emancipation and the end of the Underground Railroad. As the Underground Railroad was composed of a loose network of individuals – enslaved and free – there is little documentation on how it operated. Fortunately, a number of people recorded their participation, including Pamela Brown Thomas. She wrote about how she and her husband, Nathan, harbored freedom seekers at their house. Known as the Dr. Nathan Thomas House, in Schoolcraft, Michigan, Pamela and her family assisted approximately 1,000 to 1,500 freedom seekers.

Legacy of the Underground Railroad

There are places associated with Underground Railroad located across the U.S., and a number of national preservation programs are dedicated to documenting these sites. The National Park Service’s Network to Freedom program, for example, consists of sites with a verifiable connection to the Underground Railroad. Through collaboration with government entities, individuals, and organizations, the Network to Freedom honors, preserves, and promotes the history of resistance to enslavement through escape and flight. The National Park Service also features a website about the Underground Railroad and associated places.

Another way to recognize the places of the Underground Railroad is through the National Register of Historic Places. This National Park Service program coordinates and supports public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America's historic and archeological resources. A number of National Register properties have a connection to the Underground Railroad. The Barney L. Ford Building in Denver, Colorado is one such place. Barney escaped bondage with the assistance of the Underground Railroad. After making a successful journey to Chicago, he used his freedom to assist others. Barney eventually relocated to Denver where he established himself as a businessman. He owned a barbershop, hair salon, several restaurants, and a hotel. Barney also advocated for Black civil rights and played a significant role in the admission of Colorado to the Union as a free state.

Places such as the Barney L. Ford Building help tell the story of the Underground Railroad and its members – both free and enslaved. By nominating places to the Network to Freedom or to the National Register, members of the public can help recognize and preserve sites, structures, and landscapes associated with the Underground Railroad.

Tags

- underground railroad

- slavery and abolition

- abolitionist movement

- abolitionists

- slavery

- network to freedom

- african american history

- african american women

- women’s history

- harriet tubman

- african american sites

- shaping the political landscape

- michigan

- new jersey

- colorado

- massachusetts

- ohio

- national register of historic places

- nrhp listing

- places of article

- places of...