Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Nina Otero Warren.

Previous: Learning from Nina Otero Warren

Article

Deftly negotiating between Hispano, Anglo, and American Indian worlds throughout her life, Adelina Isabel Emilia Luna Otero was born on October 23, 1881 on her family’s hacienda near Los Lunas, New Mexico. The Otero family were wealthy and politically powerful in the Rio Abajo (Lower River) region of what is now New Mexico. The family of her mother, Eloisa Luna Otero, were descended from some of the earliest colonists in New Mexico; the family of her father, Manuel B. Otero, traced his lineage to the Spanish occupation of the area in the 1700s. As a child, she was known as Adelina Otero; as an adult, friends and family called her Nina.

Nina and her family moved to Santa Fe in the New Mexico Territory when Nina was sixteen. Nina became a regular fixture in the social life of the Santa Fe elite, described as “a graceful, intelligent young woman with an indomitable disposition,” and “high spirited and independent.” She met her husband, Rawson D. Warren, in 1907. They married on June 25, 1908, and Nina became Nina Otero-Warren.

Unhappy in her marriage, Nina divorced her husband after only two years. Since divorce was strongly frowned upon in both Anglo and Hispano cultures, Nina described herself as a widow, and kept Otero-Warren as her last name.

Nina became active in New Mexico politics, particularly in the fight for women's suffrage. Despite family obligations that took her to New York City for two years and then back to Santa Fe, she continued her work. Her suffrage work caught the attention of Alice Paul, who tapped Nina in 1917 to head the New Mexico chapter of the Congressional Union (precursor to the National Woman’s Party). Paul and other suffragists had realized that the support of Hispano’s in New Mexico was crucial to winning suffrage; Nina was an ideal choice. She insisted that suffrage literature be published in both English and Spanish, in order to reach the widest audience.

In 1921, Otero-Warren ran for federal office, campaigning to be the Republican Party nominee for New Mexico to the US House of Representatives. She won the nomination, but lost the election by less than nine percent.

Throughout her life, Nina was known both for her proper, mannered expectations of others and her unconventional personal life. Nina never remarried or had children of her own, but served as “La Nina” or godmother to her siblings, nieces and nephews, and arguably to her community. In the early 1930s, she and her partner Mamie Meadors -- whom she had met in the 1920s -- homesteaded, establishing a ranch called “Las Dos” (The Two Women) twelve miles outside of Santa Fe.

Nina died on January 3, 1965 in the Santa Fe home she grew up in. She had been administering the property after the death of her brother two years’ prior. You can read more about her life here. Below, you will discover some of the places associated with Nina's work towards women's suffrage.

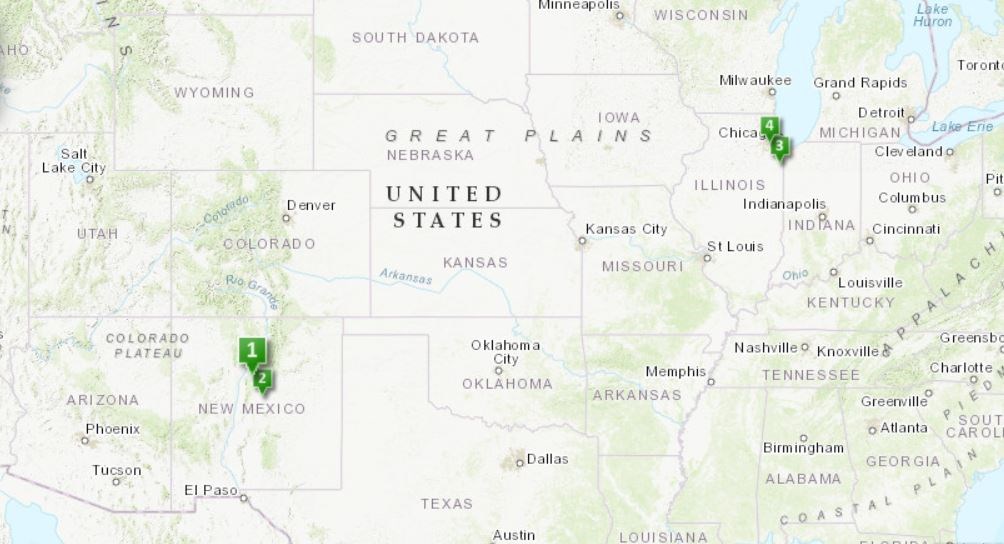

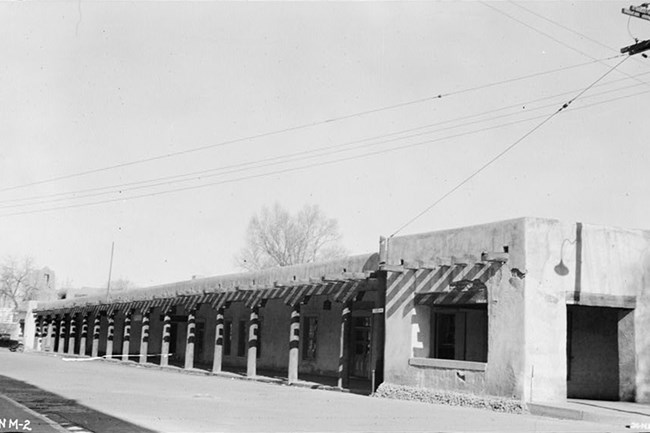

The Palace of the Governors has served numerous functions since its construction in 1610. In 1915, the structure became the headquarters of the Santa Fe branch of the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage. At the Palace, suffragists like Adelina “Nina” Otero-Warren hosted meetings and planned events to increase accessibility and inclusivity among New Mexico’s voters. Nina prioritized printing suffrage literature in Spanish and English to garner support from Hispanos and whites.

The Palace of the Governors currently houses the Museum of New Mexico. In 1934, the building was documented by the Historic American Buildings Survey. On October 9, 1960, the Palace of the Governors was designated as a National Historic Landmark. It was listed in the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.

Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress (https://www.loc.gov/item/2017847122/).

As Santa Fe’s social and economic hub since its establishment in 1609, the Santa Fe Plaza also became a center of suffrage activity during the early 20th century. With the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage New Mexico headquarters, the Second Governor’s Mansion, and U.S. Senator Thomas Benton Catron’s law offices all bordering the Plaza, the city center provided an accessible, public location for Congressional Union suffragists to organize and demonstrate.

While the surrounding buildings have undergone many changes over the years, the Plaza itself remains. And it remains a site of dissent. On Indigenous Peoples' Day 2020, protesters toppled the central obelisk. The monument, erected after the Civil War, had been controversial for generations due to one of its inscriptions: "To the heroes who have fallen in various battles with savage Indians in the Territory of New Mexico."

The Santa Fe Plaza was designated as a National Landmark on December 19, 1960 and added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 15, 1966.

Due to its prime location and luxurious amenities, the Blackstone Hotel attracted prominent guests including several U.S. presidents. These political connections granted its neighboring building the Blackstone Theatre a peak reputation as the venue for the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU) convention headquarters. Both the CU and the National American Woman Suffrage Association held conventions in Chicago that coincided with the 1916 Republican National Convention to petition the party to incorporate women’s suffrage into its platform.

On May 8, 1986, the Blackstone Hotel was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

The Auditorium Building, a prominent Chicago hotel and theater, provided convention space for the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CU) in June 1916. This convention coincided with the Republican National Convention. Members of the CU and its extension organization, the National Woman’s Party (NW) gathered in Chicago to apply pressure to Democratic president Woodrow Wilson by garnering support for women’s suffrage from his opponents. In October 1916, President Wilson spoke at the Auditorium Building. A mob of the President’s supporters violently attacked NWP protestors at the event.

The Historic American Buildings Survey documented the theater in August 1963 and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places on April 17, 1970. The Auditorium Building was designated a National Historic Landmark on May 15, 1975.

Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Nina Otero Warren.

Previous: Learning from Nina Otero Warren

Last updated: July 14, 2021