Last updated: January 15, 2026

Article

Schools on the Boston Harbor Islands

Learn about the unique history of schooling on six of the islands within the Boston Harbor Islands National and State Park.

Thompson Island, also known as Cathleen Stone Island

In 1832, the Boston Farm School Society, organized by John Tappan, John D. Williams, and others fundraised money to build what would become the Boston Farm School. A year later, they purchased all 157-acres of Thompson Island for six thousand dollars. The private school established to provide boys, either orphans or those having a single parent, with both a classroom and trade school education.[1] While similar to other reform schools in its moral aspirations, the Farm School on Thompson Island did not accept boys who had committed any crimes:

The Farm School provided "education of boys belonging to the city of Boston, who, from extraordinary exposure to moral evil, require peculiar provision for the forming of their character, and for promoting and securing the usefulness and happiness of their lives; and who have not yet fallen into those crimes which require the interposition of the law to punish or restrain them."[2]

The Farm School merged with the Boston Asylum for Indigent Boys in 1835 to become the Boston Asylum and Farm School for Indigent Boys. Around Boston, reformers in favor of temperance and abolition supported the school financially. Boston grocer John Lucas Emmons Sr, a member of the radical abolitionist organization, the Boston Vigilance Committee, served in various leadership positions at the school. [3]

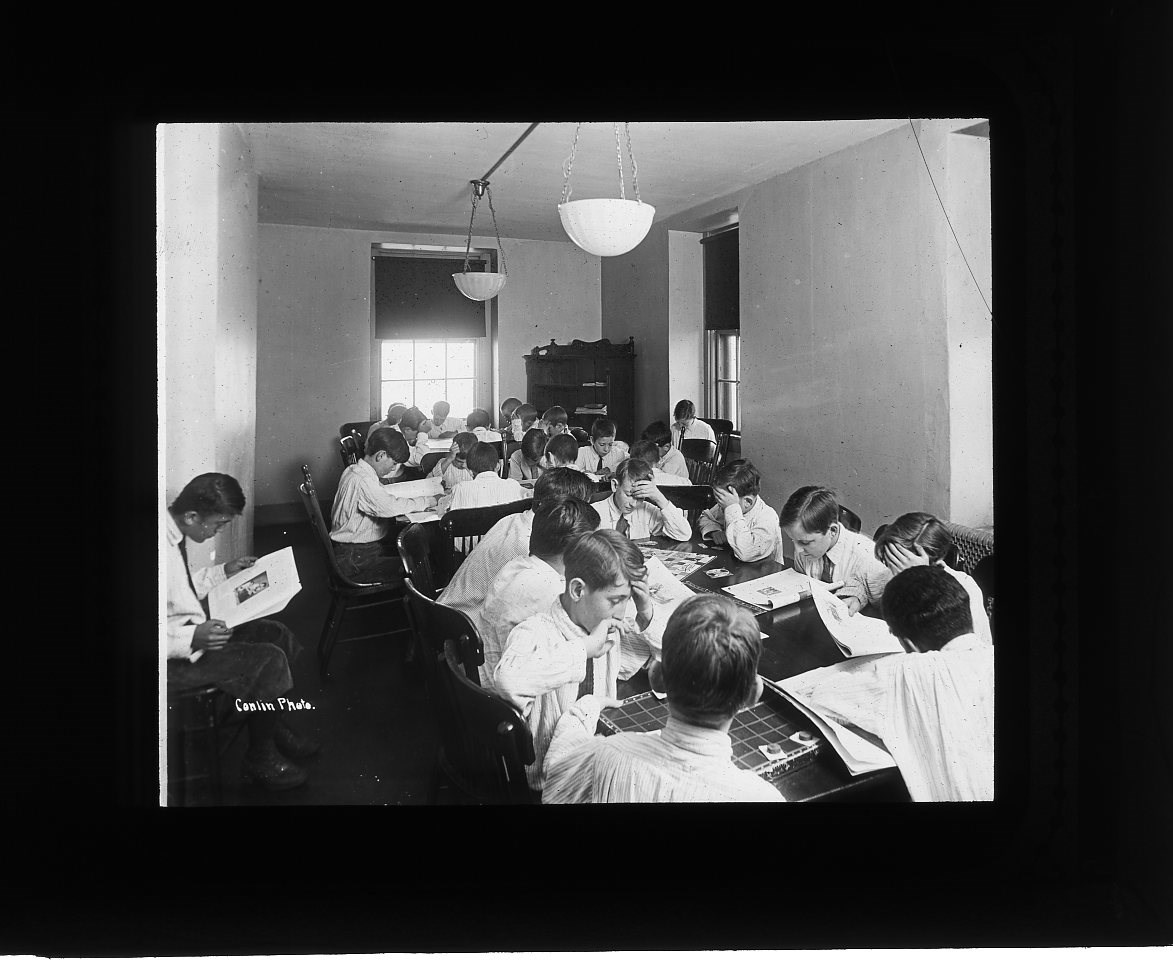

Courtesy of the UMass Boston Archives: Thompson Island Collection

On the island, students spent time in the classroom while also learning fundamentals of agriculture. In the Thompson’s Island Beacon, a student-run newspaper started in 1897, students wrote about subjects concerning themselves, the island, their schooling, and their interests. In the first issue, the newspaper included pieces on lobsters, digging clams, high tides, the frigate Constitution, and taking care of the grounds. Superintendent Charles H. Bradley wrote, "Thompson’s Island Beacon sends its light for the first time across the waters of Boston Harbor."[4]

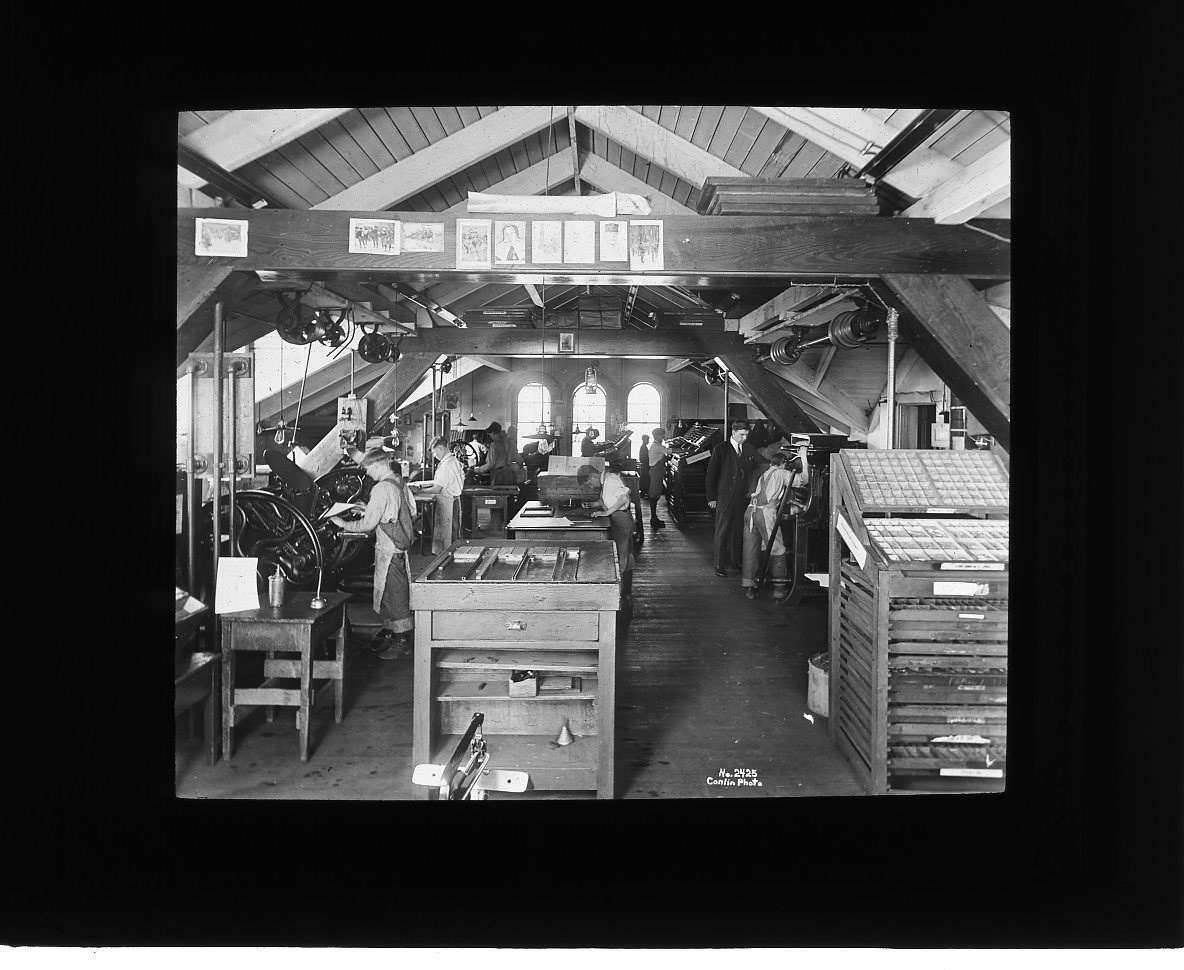

Courtesy of the UMass Boston Archives: Thompson Island Collection

Reorganized in the 1954, The Boston Farm School became the Thompson Academy, retiring from the farm and trade aspects of education. The Academy pursued environmental and experiential education. In 1975, the Academy became the Thompson Island Education Center, hosting "short-term educational trips to complement Boston Public Schools’ curriculum." In 1988, the education center partnered with an outdoor education organization, Outward Bound, changing to the Thompson Island Outward Bound Education Center. The Island now serves as the location for educational expeditions. The school, renamed to Cathleen Stone Island Outward Bound School in 2024, recognizes Cathleen D. Stone's commitment to environmental activism and education. Similar to the Boston Farm School opened over a century earlier, Outward Bound education encourages youth to experience and learn about the environment on the Boston Harbor Islands.[5]

Deer and Rainsford Islands

Schools on Rainsford and Deer Islands differed from the other islands, and Boston too. These schools served as reformatories for children detained on the islands, many of whom the state outcast or were involved in petty crimes. As part of the carceral system on Rainsford Island, The Boys Reform School, later the Suffolk School for Boys, sought to be "a moral hospital for the curing and up-building of the moral condition of the boy, just as an ordinary hospital caters to the physical needs of the sick."[6] On Deer Island in the 1870s and 1880s, schools served pauper boys and girls, as well as "truants" and those living in the "Girl’s House of Reformation" on the island.[7]

City of Boston Archives

Detainees on the island, purposefully isolated from the mainland, received education mostly in the form of training for industry. The status of the students influenced the way administrators and teachers treated them. For example, the Boys Reform School on Rainsford Island "subjected these boys to a more rigid discipline."[8]

City of Boston Archives

The schools on both Deer and Rainsford Islands raise questions about the nature of this type of reform education, and how they can contribute to the isolation and mistreatment of children. Unlike the Boston Farm School, these schools did not provide the same support for their students. The Suffolk School faced investigations into its employees and improper treatment of students in 1899.[9] These schools are entangled in the fraught history of pauperism and incarceration on these two islands.

Spectacle Island

Spectacle Island opened a school to serve the children of those employed and living on the island in 1886.[10] In 1905, the first person, Frank William Rollins, graduated on Spectacle after joining the school in 1899. The Boston Globe dubbed the school "the lease known of any of the Boston Public Schools."[11] The school’s limited enrollment garnered this designation. The following year, another single student graduated from the school, named Sarah Tarr.[12]

In 1912, the Boston School Committee ordered the superintendent of Boston Public Schools to close the school on Spectacle Island due to its lack of attendance.[13]

Long Island

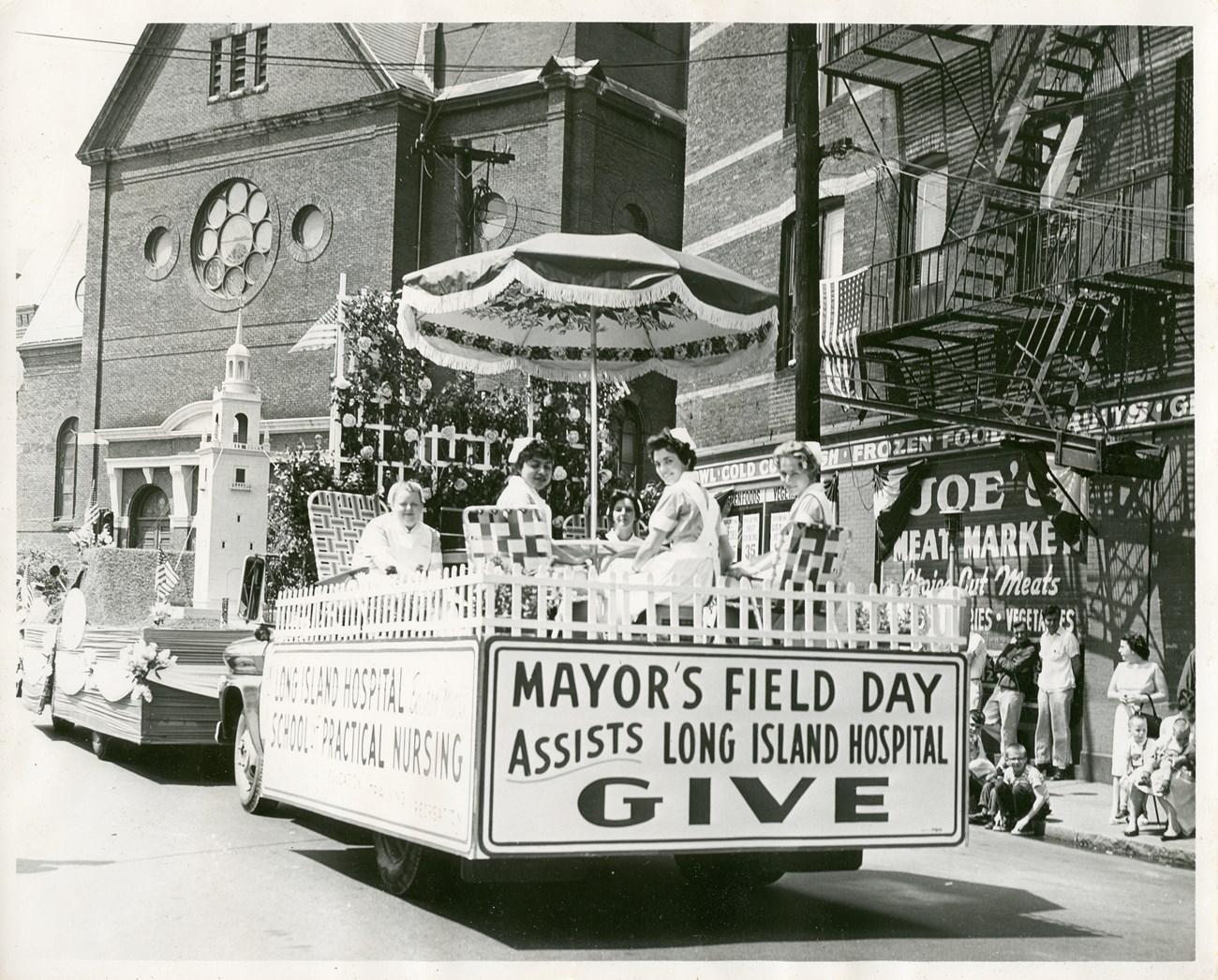

Shortly after the City of Boston opened the hospital on Long Island in 1893, a nursing school opened on the island in 1895. The first seven nurses graduated from the school in the following year. The school closed in 1937, but it later reopened as the Attendant’s Nursing School.[14]

City of Boston Archives

In addition to its nursing school, Long Island also supported students who lived on the island in the hospitals. Education extended to those unable to attend public schools in Boston due to hospitalization, even in the early 20th century. In September 1933, the Long Island Hospital School began its school year, similar to that of the Boston City Hospital School on the mainland. In addition to a classroom, teachers taught beside students at their cots.[15]

Boston Public Library

Gallops Island

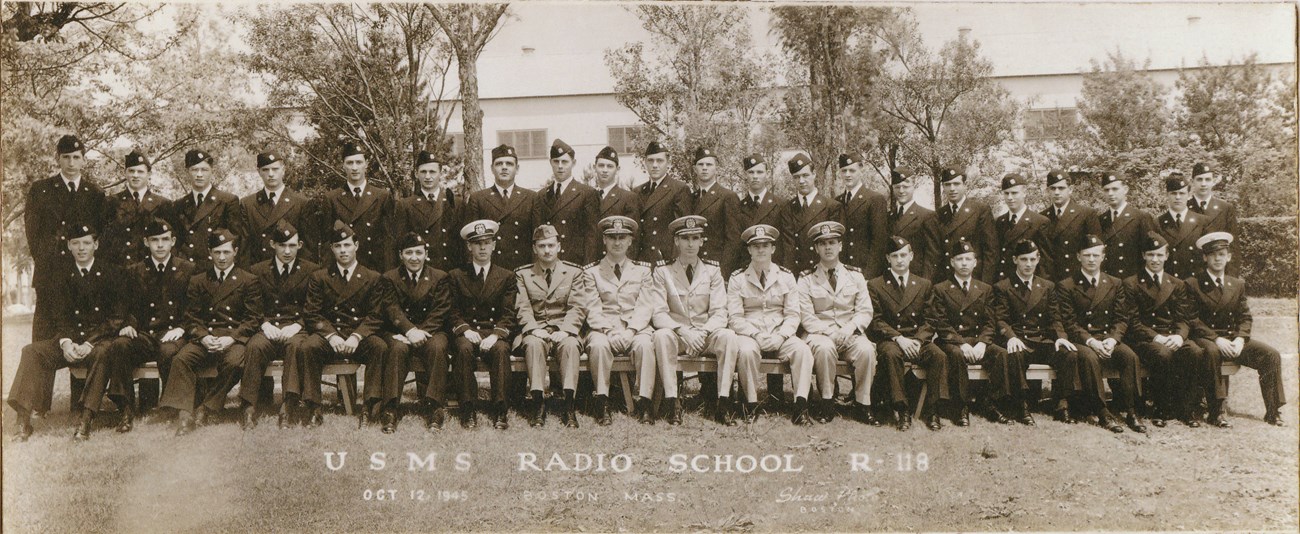

While the second World War raged overseas, in 1940, the Coast Guard established a maritime radio school on Gallops Island. The training station became one of the largest of its kind in the world, able to host over one thousand soldiers at a time for a 29-week course. Recruits from across the country arrived in Boston for a chance to get at sea, many sent to Gallops Island for radio training. One young soldier from Michigan had his first "look at the sea" at the Boston Harbor.[16]

Contributor: Saul Reichbach

Courtesy of the UMass Boston Archives: Mass. Memories Road Show Collection

Closing in 1945, the United States Maritime Radio School sent its remaining 650 students to New York.[17]

Footnotes

[1] Robert S. Pickett, "Institutions for the Reformation of Juvenile Delinquents (1825–59)." In House of Refuge: Origins of Juvenile Reform in New York State, 1815-1857, Syracuse University Press, 1969, 9, 94.; The Farm and Trades School, Thompson's Island, Boston, Mass., The Farm and Trades School Press, 1930, University of Massachusetts, Boston, Archive.org, 20.

[2] Thompson's Island Beacon, volume 1, no.1-12, Thompson Island Collection at University of Massachusetts, Boston, Thompson's Island Beacon, volume 01, numbers 1-12 - Thompson Island Collection - Open Archives at UMass Boston.

[3] Boston Evening Transcript, April 20, 1894, 8.

[4]Thompson's Island Beacon, volume 1, no.1-12, Thompson Island Collection at University of Massachusetts, Boston, Thompson's Island Beacon, volume 01, numbers 1-12 - Thompson Island Collection - Open Archives at UMass Boston.

[5] "Our History," Cathleen Stone Island, accessed July 31, 2024, Thompson Island Outward Bound History (cathleenstoneisland.org).

[6] A Brief History of Rainsford Island, Suffolk School for Boys, 1915, Boston Public Library, Archive.org, 8.

[7] Boston Evening Transcript, March 27, 1877, 2; Boston Evening Transcript, April 9, 1872, 1; Boston Globe, August 29, 1882, 2; History of the Pauper Boys School at Deer Island, Board of Directors for Public Institutions, Boston, Mass., 1876, Boston Public Library, Archive.org, 6.

[8]A Brief History of Rainsford Island, Suffolk School for Boys, 1915, Boston Public Library, Archive.org, 4.

[9] North Adams Transcript, April 26, 1899, 6.

[10] Annual Report, Boston School Committee, 1885, Boston Public Library, Archive.org, 168.

[11] Boston Globe, June 27, 1905, 14.

[12] Boston Globe, June 24, 1906, 17.

[13] Boston Globe, November 5, 1912, 9.

[14] Boston Evening Transcript, September 2, 1896, 5; "Cultural Landscape Report Boston Harbor Islands National and State Park Volume 2: Exisiting Conditions," Olmsted Center for Landscape Preservation, National Park Service, 2017.

[15] Boston Globe, September 8, 1933, 12; Annual Report of the Superintendent, Boston Public Schools, October 1923, Boston Public Library, Archive.org, 72.

[16] Boston Globe, January 31, 1943, 49.

[17] The Morning Union, August 30, 1945, 4.