Last updated: November 29, 2024

Article

Taking the Pulse of a Forest

Forests worldwide are experiencing die-offs linked to warming and drought. Is this pattern playing out in older forests of western Washington?

NPS Photo

Pacific Northwest forests are vital living systems, cycling huge quantities of carbon and nutrients, filtering pollutants from waterways, and serving as a living bulwark against climate change. An average acre of Pacific Northwest forest locks away 147 tons of carbon, among the highest of any forests in the world.

Among all forests in the region, the oldest play yet another crucial role—as climate refugia. Heat-sensitive species like the hermit warbler are more stable in old-growth forests, likely thanks to cooler microclimates and a varied buffet of food sources. Older and taller forests also proved more resilient during the 2020 megafires in the Cascades, sheltering entire communities of life from the blaze.

However, these safe havens themselves are at risk. Recent decades have brought higher temperatures and lower snowpack to the Pacific Northwest. As temperatures rise, evaporative demand (loss of water from the ground to the air) rises as well. Even the rainiest forests in this region have experienced a “climatic water deficit”—in other words, they get thirsty. When trees compete for limited water, they become stressed and vulnerable to insects, disease, and other threats.

How are mature and old-growth forests coping with the stress?

To find out, ecologists with the North Coast and Cascades Inventory and Monitoring Network asked four questions:

- Over the decade from 2008–2018, have trees died more rapidly than the background rate of 1% per year?

- Has mortality increased during the second half of the decade, compared to the first?

- Do different sized trees die at different rates?

- Is drought to blame for individual tree deaths?

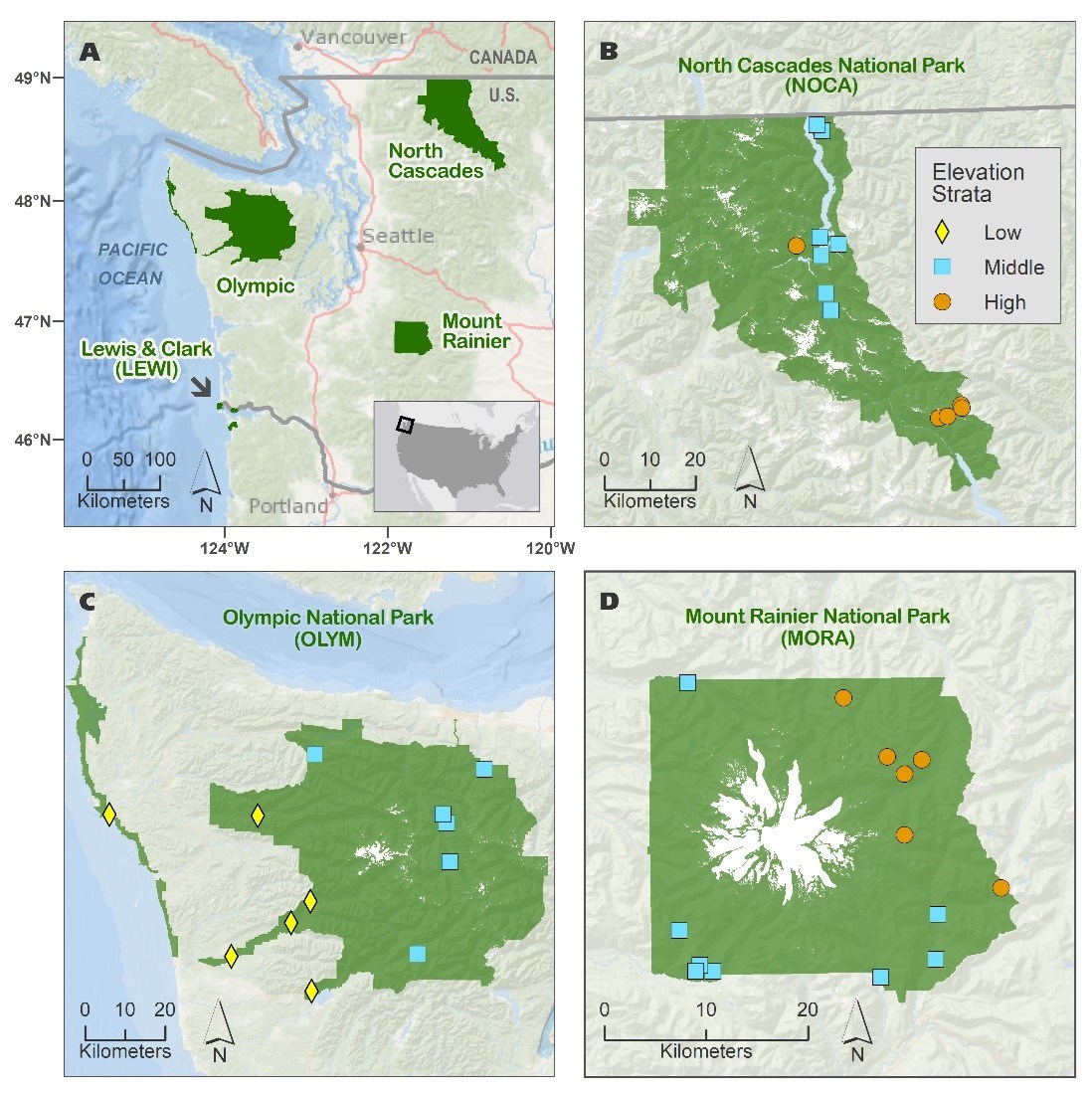

To measure forest health across the region, researchers set up 45 permanent monitoring plots in mature and old-growth forests starting in 2008. These plots were spread across low, middle, and high elevations so that results would represent several different forest types.

Figure from Acker et al., 2023

Every year from 2008–2013 and once more in 2018, research teams hiked out to each of the 100-meter-square plots. At the first visit, researchers recorded the species, size, and condition of each tree and attached a small metal tag that let them identify it in future years. Each time they returned, they recorded any new deaths since the last visit.

Surprising Results

With ten years of data, researchers returned to the study questions. Contrary to expectations, they did not find elevated mortality in any tree size group, at any elevation. Furthermore, there was no general rise in mortality over the course of the ten-year study. As expected, smaller trees were at a higher risk of death than their larger neighbors.

However, when researchers looked at factors connected to individual tree deaths, they found no overall connection to drought. In fact, they were surprised to find just one climate-related pattern: more trees died standing following winters when the atmosphere had more moisture. Could heavy winter snowpacks be leading to shorter growing seasons? Or could this mean just the opposite – that damp winters indicate more snow is falling as rain, spelling a long, dry summer ahead?

“Our forests as of 2018 are defying global odds in not demonstrating increased mortality. But we can’t assume they are safe.”

– Beth Fallon

NPS Photo/Acker

What’s next for our forests?

Up to 2018, protected mature and old-growth forests in the Pacific Northwest seemed to be standing strong in the face of climate change. However, the link between one climate variable and mortality hints at the possibility of changes to come. Continued monitoring will be needed to spot signs of stress, especially in light of increasingly extreme events like the 2021 heat dome.

The heartbeat of the forest is slow; some trees monitored in this study put down roots in the 1500s. While this ten-year period captures just one short chapter in a very long story, combined with other research it expands our ability to spot emerging issues and care for these forests into the future.

“People conserved these forests. This is our legacy, this is our heritage, and we want to understand what’s happening to it in the face of climate change and hopefully protect this biodiversity.

– Marie Denn

Study Leads

|

Steven Acker, Ph.D. Plant Ecologist, NPS and US Forest Service (retired)

|

|

John Boetsch Ecologist, North Coast and Cascades Inventory and Monitoring Network

|

|

Beth Fallon, Ph.D. Plant Ecologist, Mount Rainier National Park

|

|

Marie Denn Aquatic Ecologist, NPS Water Resources Division

|

Study Citation

Acker, Steven A., John R. Boetsch, Beth Fallon, and Marie Denn. “Stable Background Tree Mortality in Mature and Old-Growth Forests in Western Washington (NW USA). Forest Ecology and Management 532, (2023): 120817. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2023.120817. Read study >