Last updated: August 29, 2025

Article

The Celebrity Effect: How Famous Wildlife Can Lead to Risky Behavior

Wild animals who become internet sensations can be effective ambassadors for conservation. But they may also detract from broader management goals, like keeping visitors safe.

By Todd Cherry, Chandler Hubbard, and Lynne Lewis

About this article

This article was originally published in the "Perspectives" section of Park Science magazine, Volume 39, Number 2, Summer 2025 (August 29, 2025).

Chandler Hubbard

Forget red carpets and velvet ropes. The rugged outdoors of national parks have some of the biggest celebrities. The annual Fat Bear Week competition draws thousands of people to Katmai National Park in Alaska each summer. These visitors are hoping to see the famed “competitors.” Grand Teton National Park’s 400-pound Grizzly 399 had over 60,000 followers on Instagram at the time of her passing. The well-known “Hollywood Cat” (known to biologists as P-22) was the subject of documentaries and artwork. A picture of him with the iconic Hollywood sign in the background appeared in the December 2013 issue of National Geographic. When he died in 2023, six thousand people attended his funeral at the Greek Theater in Los Angeles.

Wildlife conservation may benefit from this kind of public enthusiasm. But celebrity status can also create new challenges for protecting animals and ecosystems. Our team of scientists surveyed 688 visitors in Grand Teton National Park in June and July 2024. An analysis of the unpublished data shows that visitors change their plans when they face the risk of a grizzly encounter. But not if the risk involves a celebrity bear.

Queen of the Tetons

As interest in wildlife viewing increases, social media provides a far-reaching way for people to promote individual animals to celebrity status. Grizzly 399 was a long-time matriarch in Grand Teton National Park, Wyoming. Prior to her death in 2024, she attracted thousands of people and nearly 50 wildlife photographers to the park each year. Photographer Thomas Mangelsen created an Instagram account for her, to promote responsible wildlife viewing and conservation.

Chandler Hubbard

Some studies have found that people respond to celebrity animals with greater support for conservation. In a statement made after her death, Superintendent Chip Jenkins said Grizzly 399 “has been perhaps the most prominent ambassador for the species. She has inspired countless visitors into conservation stewardship around the world.” When it comes to species and ecosystem management, though, research indicates that elevating an individual animal can be counterproductive.

The Celebrity Draw

Many wildlife managers, biologists, and some journalists resist the rise of celebrity wildlife. This is because attention on single animals can detract from conservation goals that focus on whole populations and ecosystems. In the case of Grizzly 399, managers adopted 399-specific management practices. This included creating a security detail to manage her treks through town, where other, non-celebrity bears would simply have been relocated or removed.

Visitation to Brooks Camp in Katmai National Park more than doubled after the park installed live webcams in 2012.

But Grizzly 399 and others like her often achieve celebrity status despite the aims of wildlife managers. This is partly because much of social media operates outside managers’ influence. Some estimates show that social media exposure can increase visitation at national parks by 16 to 22 percent. Focusing attention on particular individuals can further increase people’s interest in visiting. A 2023 survey revealed that visitation to Brooks Camp in Katmai National Park more than doubled after the park installed live webcams in 2012. Most visitors surveyed said the webcams and the desire to see individual bears to whom they’d become attached were the reasons they decided to visit the park.

Image credit: NPS

Given this new media landscape, wildlife managers may have to balance focusing on the needs of an entire wildlife population against focusing on the special challenges of managing a celebrity animal. One critical consideration in all this is knowing exactly how celebrity status affects visitors’ perceptions of wildlife risk and human-wildlife encounters.

Fluctuating Perceptions

In our study of visitor perceptions in Grand Teton National Park, we first measured how visitors felt about the inherent risks when encountering wildlife. We asked, “How worried are you about having a grizzly bear encounter when hiking?” On a 10-point Likert scale, respondents indicated, on average, a moderate level of concern (4 out of 10).

We also asked visitors what they thought was the likelihood of a bear encounter. We defined this as being within 50 yards of a bear. Respondents, on average, believed there was about a 5 percent chance of encountering a bear. In the event of an encounter, they thought there was a 45 percent chance it would result in significant injury or death.

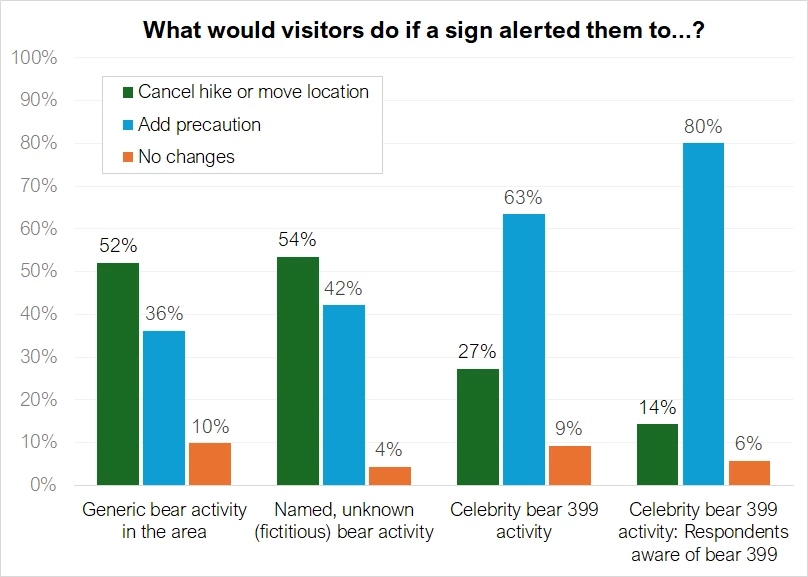

In the case of a generic (unknown) bear, 52 percent of respondents said they would cancel plans or move to another location.

When we asked visitors what current actions they take to reduce the chance of harm from a grizzly encounter, nearly all said they take some action. Eighty-nine percent said they stay on designated trails. Eighty-eight percent said they hike in groups, and 75 percent said they carry bear spray. Overall, visitors seemed to understand and respond to the hazards of encountering a bear in the park.

We then introduced imaginary scenarios with an elevated likelihood of a visitor encountering a (generic) grizzly bear. We first asked visitors how they would respond if they arrived at a trailhead to take a hike and saw an official sign that said, “Warning: multiple reports of grizzly bear activity in the area.” Would they (a) cancel plans and return another day, (b) continue with plans but with greater precautions, (c) continue with plans with no additional precautions, or (d) adjust plans by moving to another location? In the case of a generic (unknown) bear, 52 percent of respondents said they would cancel plans or move to another location.

Image credit: Chandler Hubbard

To identify the influence of celebrity status, we conducted a separate survey with different visitors. In this one, the hypothetical trailhead warning sign said, “Warning: Grizzly Bear 399 reported in the area.” When we asked visitors how they would respond, only 27 percent surveyed said they would cancel plans or move to a different location. Although respondents said they would take additional precautions, they were more willing to continue on the trail if the bear activity was associated with 399 than with a generic bear.

Known vs. Unknown Bears

Celebrity status matters more if a person knows about the celebrity animal. We asked a follow-up question in the 399 version of the survey to learn if the visitor had heard of Grizzly 399. For respondents who knew about 399, only 14 percent said they would avoid the trail when the risk of an encounter was due to 399. This stands in stark contrast to the 52 percent who said they would avoid the trail when the risk was due to a generic bear.

For respondents who knew about 399, only 14 percent said they would avoid the trail.

To separate the influence of celebrity status from that of a named but unknown animal, we conducted a third version of the survey. This one attributed the increased risk to an unknown, individual grizzly bear. In this case, the imaginary trailhead sign said, “Warning: Grizzly Bear 762 reported in the area.” We know respondents were unaware of 762 because, at the time, there was no Grizzly Bear 762.

NPS / J. Weinberg-McClosky. Data courtesy of Todd Cherry.

The bar chart is titled “What would visitors do if a sign alerted them to…?"

On the y axis are percentages from 0% at the bottom to 100% at the top. On the x axis are four categories, listed from left to right:

-

Generic bear activity in the area

-

Named, unknown (fictitious) bear activity

-

Celebrity bear 399 activity

-

Celebrity bear 399 activity: Respondents aware of bear 399

Each category has three bars in different colors, corresponding to three different responses, from left to right:

-

Cancel hike or move location (green)

-

Add precaution (blue)

-

No changes (orange)

The three responses are also listed in the legend on the upper left of the chart.

For the “Generic bear activity in the area” category, the green bar shows 52%, the blue bar 36%, and the orange bar 10%.

For the “Named, unknown (fictitious) bear activity” category, the green bar shows 54%, the blue bar 42%, and the orange bar 4%.

For the “Celebrity bear 399 activity” category, the green bar shows 27%, the blue bar shows 63%, and the orange bar shows 9%.

For the “Celebrity bear 399 activity: Respondents aware of bear 399,” category, the green bar shows 14%, the blue bar shows 80%, and the orange bar shows 6%.

People responded similarly whether the risk was due to a generic bear or a fictitious individual bear. In the case of the fictitious, specific bear, 54 percent of respondents said they would avoid the trail. This is similar to the 52 percent in the case of a generic bear. This tells us that it’s celebrity status, not individual identity, that explains the greater willingness of visitors to accept increased risk.

Fame Matters

Growing interest in looking at wildlife, fueled by celebrity animals, creates challenges for park management. “Managing the human-bear interface to keep people safe and bears wild is complex,” said Grand Teton Bear Biologist Justin Schwabedissen. “Providing hikers, campers, and other outdoor users with relevant and effective bear-safety messaging is critical to minimizing human-bear conflicts.”

The key takeaway from our study is that fame matters. Celebrity status changes how people respond to the risk of encountering potentially harmful animals. People may be more willing to take risks because they desire to see the celebrity animals or believe they’re less dangerous, or both. This introduces a new consideration when creating management policies regarding human-wildlife encounters that serve broader conservation goals. Jenn Newton, the park’s social scientist, said, “Learning more about visitors' perceptions of risk, and how different messaging can affect that perception and human behavior, is invaluable as we think about how to best communicate to visitors.”

About the authors

Todd Cherry is the John S. Bugas distinguished professor in the Department of Economics at the University of Wyoming. Image courtesy of Todd Cherry.

Chandler Hubbard is a PhD student in economics at the University of Wyoming. Image courtesy of Chandler Hubbard.

Lynne Lewis is a professor of agricultural and resource economics at Colorado State University and the Elmer W. Campbell professor of economics, emerita, at Bates College. Image courtesy of Lynne Lewis.

Cite this article

Cherry, Todd, Chandler Hubbard, and Lynne Lewis. 2025. “The Celebrity Effect: How Famous Wildlife Can Lead to Risky Behavior.” Park Science 39 (2). August 29, 2025. https://www.nps.gov/articles/000/ psv39n2_the-celebrity-effect-how-famous-wildlife-can-lead-to-risky-behavior.htm