Last updated: January 13, 2026

Article

School Desegregation Protests and Rallies Downtown

This article is part of the series "Desegregation in the Cradle of Liberty." This series explores the Black struggle for equal education in Boston from 1787 to 1976, culminating with protests and violence experienced under forced busing in Boston in the 1970s.

Desegregation Downtown

During the struggle to desegregate Boston Public schools in the 1970s, activists rallied and protested throughout the city, including at many historic sites that now compromise the National Parks of Boston. Many of these places downtown, including Faneuil Hall and the Boston Massacre site, tie directly to Boston's Revolutionary era history and sit upon the city's Freedom Trail. Activists on both sides of the desegregation issue seized upon the power of place and the upcoming bicentennial of the country's founding in 1976 to assert their voices and claim America's revolutionary legacy as their own.

Some of these key moments at historic sites downtown are explored below.

Bicentennial Commemoration of The Boston Massacre - March 5, 1975

In March 1975, the antibusing group Restore Our Alienated Rights (ROAR) saw an opportunity to link their cause with those of the founding generation. A large group of ROAR protestors staged a demonstration at the Boston Massacre Anniversary commemoration. They disrupted the reenactment by holding a mock funeral carrying a coffin with the corpse of "Miss Liberty" and the words "R.I.P Liberty. b.1776-d.1974" emblazoned across it. In doing so, they expressed their belief that their freedom had died with the Morgan v. Hennigan decision, which initiated busing in 1974.

Boston Globe article from March 6, 1975

One protester led the crowd chanting "Garrity Killed Liberty," referencing Judge Garrity, who delivered the ruling in the case. Others bore placards that read, "Boston Mourns Its Lost Freedom," and "Have You Ever Seen the Words Forced Busing in the Constitution?" In a blatant threat of impending violence if busing continued, one sign read, "You Think This Is a Massacre, Just Wait."[1]

The interruptions continued until Jack Alves, president of the Charlestown Historical Society, called out ROAR members he knew in the crowd asking them to allow the event to proceed. However, when the British reenactors fired their guns as part of the commemoration, all 400 members of the ROAR dropped to the ground as if shot. [2]

Faneuil Hall

Renowned as the "Cradle of Liberty" for its role in the early years of the American Revolution, Faneuil Hall has served as a public gathering space since its dedication in 1742. During the desegregation battles of the 1960s and 70s, activists continued that tradition of protest and debate within and around Faneuil Hall. Sometimes these rallies took place as scheduled public meetings at the hall, and other times groups stole the spotlight by interrupting scheduled events there.

Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library collection at Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections

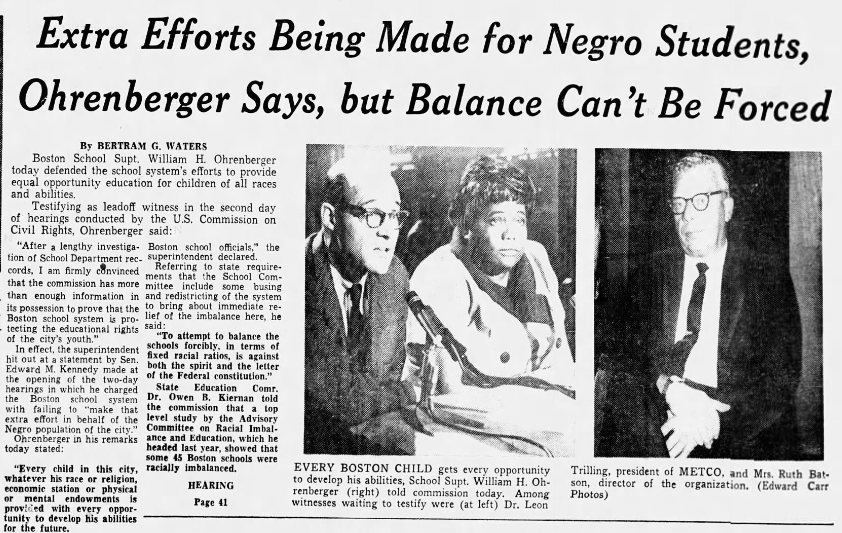

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights Hearing at Faneuil Hall

On October 4 and 5, 1966, the United States Commission on Civil Rights held hearings in Boston, Massachusetts at Faneuil Hall. Part of a national movement, these hearings intended to investigate inequities in the Boston Public School system (BPS). Superintendent William H. Ohrenberger defended BPS:

If racially imbalanced schools exist, and they do; if some of the school buildings are antiquated, and they are; if the motivation of some children is below normal, these conditions are not the result of the politics or programs of present or former Boston school officials.[3]

The Boston Globe

Ruth Batson, alongside other notable Black leaders in Boston –Rollins Griffith, Ellen Jackson, Harriet Johnson, Mel King, Paul Parks, Charles Pinderhughes, Judith Rollins, and Dr. James Teele— and a selection of students testified at the hearing on behalf of Black students.[4]

Ruth Batson told the Commission:

Under the present school system, we in Roxbury are victims of official neglect that has led to an educational gap. The School Dept. doesn't recognize that any serious problem exists in Roxbury.[5]

The Commission asked Batson whether she thought it was time for the city efforts to match the federal government both in funds and efforts to work on the school inequalities, Ruth Batson replied:

Realistically, I don't think you ask the children to suffer while you try to change someone's thinking.[6]

Boston Public Library

Mayoral Campaign of 1967

The issue of desegregation took center stage at Faneuil Hall during the Boston mayoral campaign in 1967. At the Hall, candidate Kevin White debated the staunchly anti-desegregationist school committee member Louise Day Hicks. Though White won the election, Hicks remained a powerful force in the city. In an interview before the event with the Globe, she discussed desegregation in terms of parental rights. The Boston Globe reported:

Mrs. Hicks went on to say her opposition to busing and the racial-imbalance law is supporting a predominant feeling 'among mothers' that they 'do not want their little children bused.'[7]

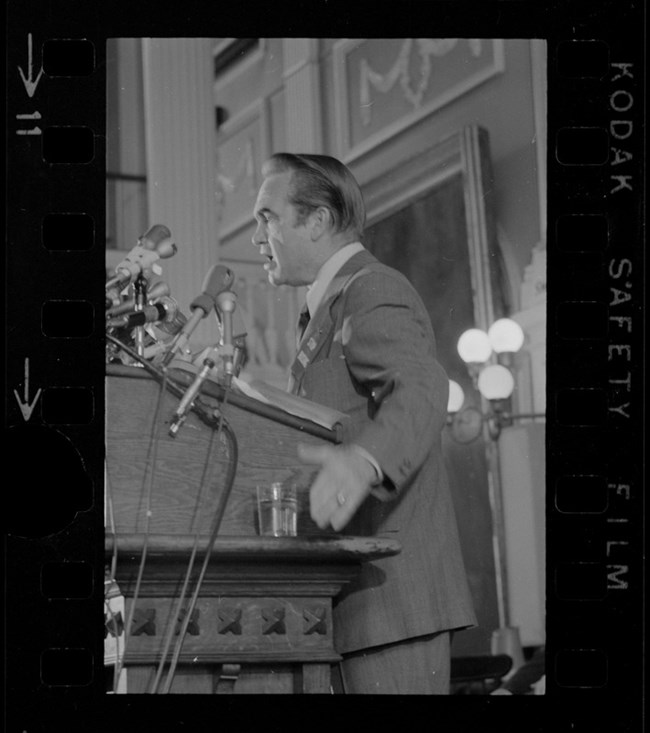

George Wallace at Faneuil Hall

Boston Public Library

During his presidential campaign in 1972, George Wallace addressed Boston supporters at Faneuil Hall. Wallace had served as governor of Alabama and won national notoriety for his openly segregationist rhetoric, policies, and public attempts to stop integration in his state. According to one newspaper, he "won cheers from the crowd" with his denunciation of busing.[8]

ERA Meeting at Faneuil Hall - April 1975

Hicks and others used Boston's revolutionary sites such as Faneuil Hall, as well as the attention garnered by the impending bicentennial, to frame their fight as analogous to that of the colonists during the days of the Revolution. They claimed to be fighting this new form of government overreach as the colonists did before them.[9]

Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library collection at Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

Hicks and other anti-busing leaders also took aim at the women's liberation movement, accusing feminists of not seeing anti-busing as a women's issue. In 1975, anti-busing advocates staged a high profile protest by incessantly interrupting an Equal Rights Amendment rally at Faneuil Hall. The event featured speakers including Kitty Dukakis, the wife of Governor Michael Dukakis, and Florence Luscomb, a suffragist and lifelong activist. The protesters shouted down the aging Luscomb and forced Dukakis to leave the hall before addressing the crowd.[10]

City Hall Plaza

Just steps away from Faneuil Hall, City Hall Plaza also served as the site of numerous protests during the desegregation struggles in Boston. In the early 1960s, Black activists staged sit-ins and protests there. Anti-busing demonstrations also took place at City Hall throughout the 1970s. Some of these rallies turned violent.

Perhaps the most infamous protest at City Hall Plaza occurred April 5, 1976, when an angry White mob violently attacked Ted Landsmark, a Black attorney, as he walked towards City Hall. A photographer captured the moment when Landsmark's assailant swung an American flag at him. Winner of the Pulitzer Prize for Photography, this image, "The Soiling of Old Glory," encapsulated the racist and violent turn the anti-busing movement took in Boston as the nation celebrated its bicentennial in one of its most historic cities.

Stanley Forman for The Boston Herald American, April 5, 1976

Ebony magazine reported on this violence "within sight and sound of Faneuil Hall, where Revolutionary patriots spawned the American Revolution."[11] The article posed the following question:

But the fact that it happened in the city of Boston, the cutting edge of the American Revolution, on the celebration of the Bicentennial of the Revolution, was truly shocking and raised large questions about the state of mind and soul of the Republic on the eve of the Third Century. DO the people of Boston, or the people of any other American city, understand what Bostonians were fighting for 200 years ago? Do they understand and believe in the Declaration of Independence? And if they don't believe in and understand the Declaration and the great dream it symbolizes, what, in God's name, are they celebrating?[12]

Overview Timeline Article

Black Struggle for Equal EducationFootnotes

[1] "Busing foes take their protest to replay of Boston Massacre," The Boston Globe, March, 6, 1875, 6.

[2] J. Anthony Lukas, "Who Owns 1776?" The New York Times, May 18, 1975.

[3] Bertram G. Waters, "Extra Efforts Being Made for Negro Students, Ohrenberger Says, but Balance Can't Be Forced," The Boston Globe, October 5, 1966, pg 1.

[4] "Hearing Before the United States Commission on Civil Rights," from Ruth Baston in The Black Educational Movement in Boston: a Sequence of historical events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 273.

[5] Bertram G. Waters, "Extra Efforts Being Made for Negro Students, Ohrenberger Says, but Balance Can’t Be Forced," The Boston Globe, October 5, 1966. 41.

[6] Bertram G. Waters, "Extra Efforts Being Made for Negro Students, Ohrenberger Says, but Balance Can't Be Forced," The Boston Globe, October 5, 1966. 41.

[7] Carol Liston, "The Boston Campaign Property and Psychology Mrs. Hicks," The Boston Globe, November 3, 1967.

[8] "Wallace pays only Mass. visit," The Boston Globe, April 25, 1972, 5.

[9] Kathleen Banks Nutter, "'Militant Mothers:' Boston, Busing, and the Bicentennial of 1976," Historical Journal of Massachusetts, (Fall 2010), 54.

[10] Kathleen Banks Nutter, "'Militant Mothers:' Boston, Busing, and the Bicentennial of 1976," Historical Journal of Massachusetts, (Fall 2010), 67.

[11] "The Bicentennial Blues," Ebony 31, no. 8 (June 1, 1976): 152.

[12] "The Bicentennial Blues," Ebony 31, no. 8 (June 1, 1976): 152.