Last updated: February 10, 2025

Article

The Black Struggle for Equal Education in Boston, 1787 to 1976

NPS Illustration/E Hanson Plass

Boston earned its nickname as the "Cradle of Liberty" by fostering the revolutionary ideals and values that serve as the foundation of this country. Included in these values is access to education. Bostonians founded the oldest public school in America - the Boston Latin School (1635) - and Boston continues to be recognized as an educational hub.

Yet this reputation only recognizes one facet of Boston's complicated history with public education.

The Black struggle for equal education in Boston began in the era just after the American Revolution. Generations of Black Bostonians have been engaged in advocating and fighting for their right to education since 1787. In their wake is a legacy of advocacy, community activism, and legal challenges spanning more than two centuries and continues to this day.

In this article series, we invite you to follow this legacy that forms a different kind of "Freedom Trail:" One that took place over much of the same ground, but spans a period from 1787 to 1976.

1787-1855: Early Black Education Movement

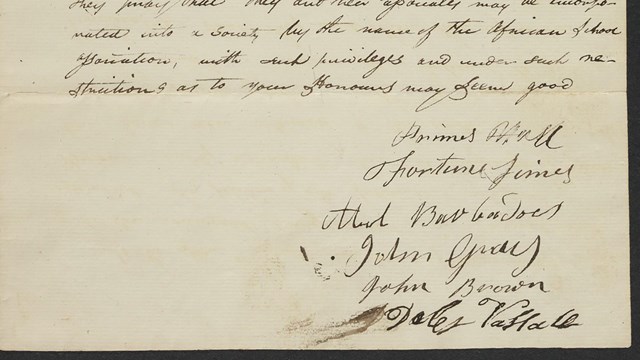

Though Boston's schools in the 1780s did not legally bar Black children from attending, Black students found themselves at the mercy of hostile teachers and fellow students. In 1787, Prince Hall and others brought the first petition for better schools to the Massachusetts General Court. The petitioners claimed Black children:

receive no benefit from the free schools in the town of Boston, which we think is a great grievance, as by woful [sic] experience we now feel the want of a common education.[1]

This petition did not succeed, nor did a similar one in 1796. In response to these setbacks, the community set up their own private school. This early school, known as the "African School," met in 1798 in the home of Prince Hall's son, Primus Hall.[2] By 1808, the school moved to the basement of the African Meeting House, then later to the Abiel Smith School in the mid-1830s.

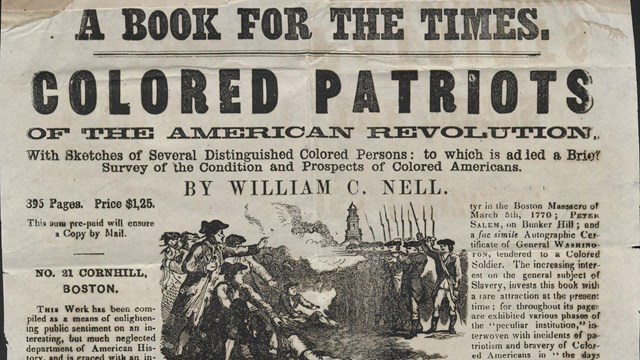

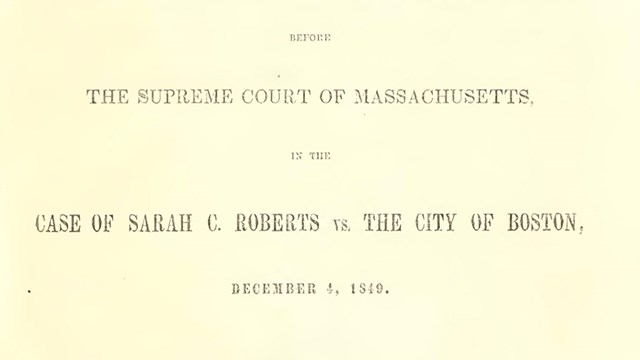

Though considered part of the Boston school system, the Smith School received significantly fewer resources, depended on outside donations, and became the default school for most of the city's Black students. This segregated school soon became the focal point in the Black community's efforts to desegregate the public schools in Boston. Local activists, including William Cooper Nell, organized boycotts and petition drives against the Smith School. In the late 1840s, Benjamin Roberts sued the city on behalf of his young daughter, Sarah, in another attempt to integrate the schools. Though they lost the case of Roberts v. City of Boston, the community forged ahead and succeeded in getting the Massachusetts legislature to outlaw segregated public schools in 1855.

Though no law or policy in Boston explicitly barred children of color from attending school, many felt unwelcome and excluded.

As one of Boston's most influential leaders, William Cooper Nell served the community as an organizer, abolitionist, and historian.

Benjamin Roberts filed a suit against the Boston Primary School Committee on behalf of his daughter.

1890s-1960s: Ethnic Neighborhoods Fight for Local Schools in a Growing City

As Boston continued to grow in both population and geographic size, and as new immigrant groups arrived in the city in great numbers, ethnic neighborhoods began to emerge. This growth from the late 1800s into the 1900s strained the Boston Public School system as each group vied for better access to quality education. By the mid-1900s, ethnic neighborhoods had solidified and race-based housing polices, such as redlining, created a segregated city.[3] Race-based segregation policies also impacted the public schools, despite federal and state laws which forbade them.

Class disparities became increasingly stark, as wealthy and middle-class neighborhoods in the city had access to newer and better maintained facilities, permanent teachers, and enough space for all students. Though not as good as the schools in the White middle-class neighborhoods, the schools in the White working-class neighborhoods, such as Charlestown and South Boston, still generally fared better than schools in Black neighborhoods, such as Roxbury.[4] In South Boston, the community used its political clout in the early 1900s to get their own high school. In Charlestown, the community mobilized during the years of Urban Renewal in the 1960s to get new schools built as well. Meanwhile, the Black community's concerns for better schools continued to be cast aside. By the 1960s and 70s, the issue of equal schools had reached a boiling point.[5]

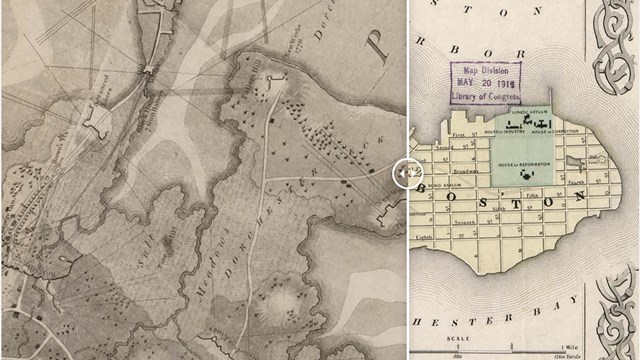

In 1804, Boston annexed the Dorchester Peninsula. Within just a few decades, it became the growing South Boston neighborhood.

City planners set their sights upon Charlestown in the 1960s. Charlestown residents mobilized to save their neighborhood.

1950s-1974: Black Education Movement in the 20th Century

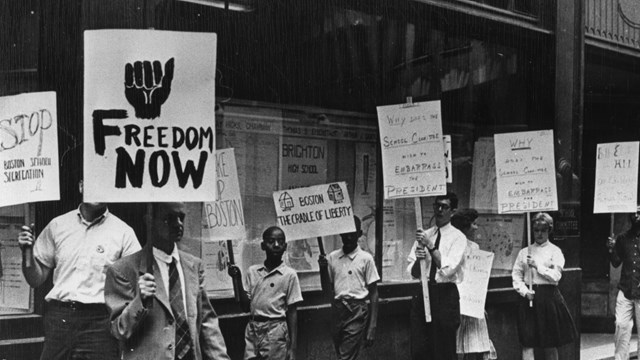

In 1963, the local branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) committed itself to the fight for desegregation. Led by fierce activist Ruth Batson, the NAACP spent the next couple of years documenting the ongoing segregation in Boston Public Schools despite the 1855 Massachusetts law and the 1954 Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision that outlawed segregation in schools.

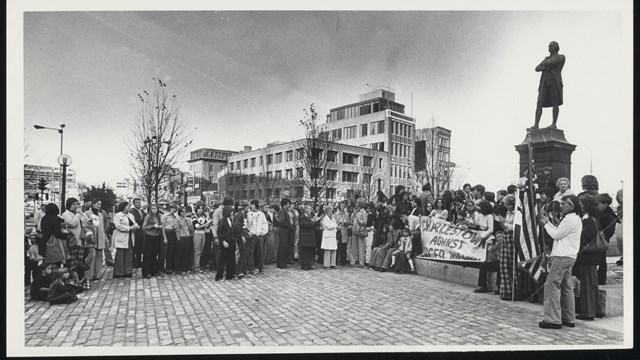

When the Boston School Committee continuously hampered these efforts and refused to acknowledge outright segregation, the NAACP sued them. The case, Morgan v. Hennigan, made it to the U.S. District Court. In 1974, the court ruled that the Boston School Committee had deliberately established and maintained separate race-based schools. To bring Boston into line with both federal and state laws, Judge W. Arthur Garrity ordered the integration of schools by what became known as "forced busing." This required busing Black children to schools in White neighborhoods, such as South Boston and Charlestown, and White children into schools in Black neighborhoods, such as Roxbury. Busing ignited a firestorm of backlash on the part of White residents and years of racial violence in the city.

In the 1950s, the Black community, particularly mothers, began organizing to combat unequal education in Boston.

In the summer of 1974, Judge W. Arthur Garrity ordered busing in the Boston Public School system.

1960s and 1970s: Protest, Debate, and Violence in the "Cradle of Liberty"

Many of the battles over equal education in the lead up and aftermath of Judge Garrity's decision took place in neighborhoods and at sites that now comprise the National Parks of Boston. Places associated with the American Revolution along the "Freedom Trail" became battlegrounds once again. These sites include the Old State House, Faneuil Hall, Bunker Hill Monument in Charlestown, Dorchester Heights in South Boston, as well as the Robert Gould Shaw/54th Regiment Memorial. Visit the interactive map in the "Desegregation in the 'Cradle of Liberty'" article, or use the article links below to further explore this tumultuous period in Boston's history

School Desegregation Protests Across Boston

At this memorial, activists rallied and protested during the 20th century Black Education Movement.

In the struggle to desegregate Boston Public schools in the 1970s, activists rallied and protested in downtown Boston.

When busing came to Charlestown in 1975, parents reacted by protesting in the streets around the Bunker Hill Monument.

Sharing a hill with South Boston High School, Dorchester Heights served as a site of unrest and protest during Boston's busing crisis.

Footnotes

[1] Robert P. Green, Jr., ed. Equal Protection and the African American Constitutional Experience, (Greenwood Press: Westport, CT, 2000), 38-39.

[2] ShaVonte’ Mills, "An African School for African Americans: Black Demands for Education in Antebellum Boston," History of Education Quarterly 61, no. 4 (2021): 478–502.

[3] Zebulon Vance Miletsky, Before Busing: A History of Boston's Long Black Freedom Struggle, (University of North Carolina Press, 2022), 82.

[4] Ruth Batson, "Higginson School District Parents letter to Mayor Collins in The Black Educational Movement in Boston: a Sequence of historical events: A Chronology," (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 85b.

[5] Jim Vabrel, A People's History of the New Boston, (University of Massachusetts Press, 2014), 22-23.