Last updated: January 13, 2026

Article

Anti-Busing Protest at Dorchester Heights

This article is part of the series "Desegregation in the Cradle of Liberty." This series explores the Black struggle for equal education in Boston from 1787 to 1976, culminating with protests and violence experienced under forced busing in Boston in the 1970s.

During the struggle to desegregate Boston public schools in the 1970s, activists rallied and protested throughout the city, including at many historic sites that now comprise the National Parks of Boston. The Dorchester Heights Monument, which commemorates the Height's role during the 1775-1776 Siege of Boston, has long served as an integral public space for community gatherings. This tradition carried on during the fight against busing in the 1970s, in part, due to the Monument's proximity to South Boston High School. Here, parents and other South Bostonians gathered to protest the buses arriving to the high school. Oftentimes, these activists called upon the revolutionary legacy of this site as their protests grew increasingly violent.

Some of these key moments at Dorchester Heights are explored below.

First Day of School

Court ordered busing in Boston Public Schools began on September 9, 1974, with the first day of school. The plan called for Black students from Roxbury to be sent to South Boston High School and White students from South Boston to be sent to Roxbury High School.

Boston Public Library

South Boston parents protested forced busing in a variety of ways. Some parents kept their children out of schools, while others harassed bused students by shouting racial slurs and throwing rocks, glass bottles, and bricks at the buses. Some parents became involved in organizations such as Restore Our Alienated Rights (ROAR) or the South Boston Information Center, which became the center of the anti-busing movement in South Boston. In an article for The New York Times, a parent reflected on their fight:

How can we celebrate our country's history when we are being denied the very rights we fought for in the Revolution? We've been denied the right to peaceably assemble. We've been denied free speech and the right to walk the streets. Police come in here escorting the buses and everything else has to give way.[1]

Restore Our Alienated Rights

Led by former Boston School Committee member Louise Day Hicks, Restore Our Alienated Rights (ROAR) became the leading parents' rights organization that demonstrated against forced busing in South Boston. While originally intending to be simply against forced busing, their racism-tinged arguments against busing helped shape a combative culture in Boston, fueling angry protests and weaponization of racial violence against the Black community. Although ROAR protestors organized many of their own events, they also often disrupted many other public events across Boston.

John Joseph Moakley Archive and Institute, Suffolk University

South Bostonians Protest

While many parents participated in ROAR-led protests, they also looked to other groups that supported their beliefs. During the second month of busing, religious leader John Doogan, who also served as the executive director of Massachusetts Citizens Against Forced Busing, led a prayer vigil at Dorchester Heights. He encouraged the "worshipers to keep vigil lights burning in their house windows and to pray daily during the busing crisis."[3]

Courtesy of the Boston Globe Library collection at Northeastern University Archives and Special Collections.

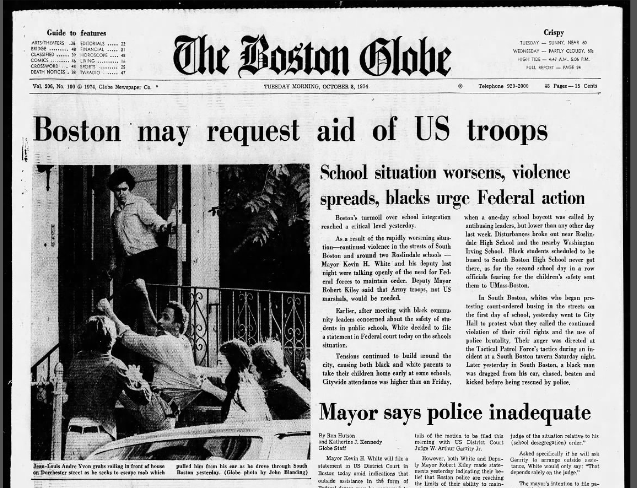

Escalating Violence

The hostile prejudice that emerged in the fight against busing augmented existing tension and prejudice in Boston. At times this prejudice escalated into racially motivated violent mob action against members of Boston's Black community. Just a month into forced school busing, in October 1974, a violent mob pulled Jean-Louis Yvon, a Black man, out of his car while driving through South Boston. They chased and beat him in the streets. Police had to step in to prevent Yvon from being beaten further.[4] This mob attack inspired fear in the Black community, leading to many Black people avoiding South Boston altogether.

Boston Globe, October 1974

Another example of the racial violence inspired by the anti-busing movement occurred at the end of the first tumultuous semester of forced busing at South Boston High School. A Black student stabbed a White student during an altercation at the school. Police arrested the Black student while the White student received medical treatment at the hospital.

When the community heard about the stabbing, a mob of South Bostonians formed around the school in anger. Louise Day Hicks arrived and attempted to control the crowd in order to allow the other Black students to go home. But she could not get control, the mob could not be tamed. Ultimately, officials sent decoy buses to the front of the school, which the mob attacked, while the Black students snuck out a side entrance to other buses waiting to take them safely out of South Boston.[5]

Political Campaigning

The Dorchester Heights Monument has long been a center of the South Boston community and continues to be a central site of gathering. Since its creation, local politicians and other leaders have used the Monument to stage political events and claim its revolutionary legacy as their own. Louise Day Hicks, former member of the Boston School Committee from 1961-1970 and United States Congress member from 1971-1973, used this legacy to gain community support.

In addition to politicians, other high-profile public figures rallied at Dorchester Heights in support of the anti-busing movement. For example, David Duke, the head of the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), came to South Boston in September 1974 to "urge them to join his organization and fight for keeping South Boston's schools all white."[6]

Overview Timeline Article

Black Struggle for Equal EducationFootnotes

[1] J. Anthony Lukas, "Who Owns 1776?" The New York Times, May 18, 1975.

[2] J. Anthony Lukas, "Who Owns 1776?" The New York Times, May 18, 1975.

[3] "Boston May Request Aid of US Troops, School Situation worsens, violence spreads, blacks urge Federal action," The Boston Globe, October 8, 1974, 1-3.

[4] Bob Sales, "Whites Chase, Beat Black Man," The Boston Globe, October 8, 1974.

[5] Ruth Batson, "South Boston High Is Under Siege When A White Student Is Stabbed," The Black Educational Movement in Boston: A Sequence of Historical Events: A Chronology, (Northeastern University School of Education, 2001), 385-386.

[6] John F. Cullen, "Police, crowds clash in S. Boston last night," The Boston Globe, September 20, 1974.