Last updated: September 18, 2023

Article

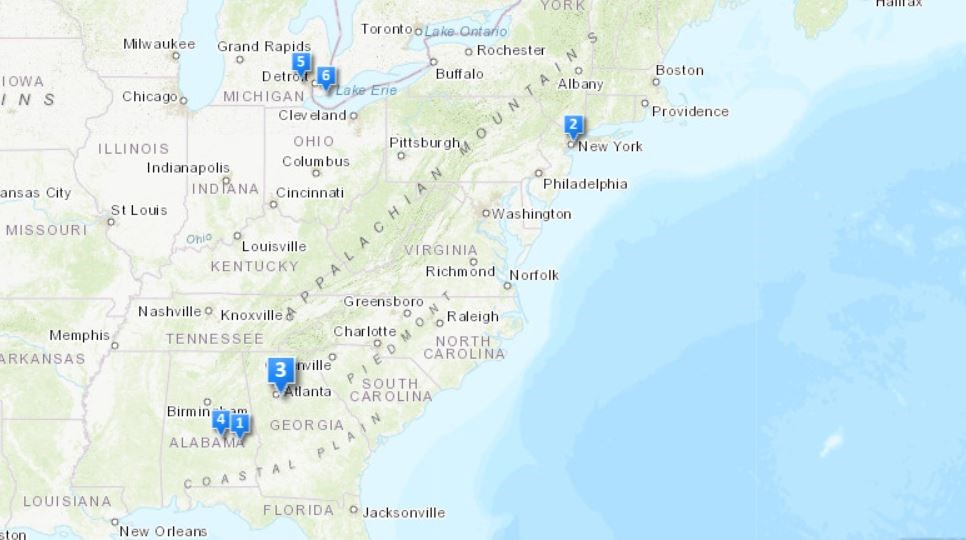

Places of Rosa Parks

Public domain.

The content for this article was researched and written by Jade Ryerson, an intern with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education.

Although Rosa Parks is perhaps best known for initiating the Montgomery bus boycott, her experience with civil rights activism is much more extensive. Parks became a member of the Montgomery Branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in 1943. She served as the local NAACP secretary for twelve years and co-founded the Montgomery Improvement Association, the organization that launched the Montgomery bus boycott, in 1955.

Parks’s work was not limited to the South. As a national figure in the civil rights movement, she traveled throughout the country to speak, attend rallies and marches, and organize meetings. This article features some of the places associated with Rosa Parks’s life and activism.

NPS photo.

1. Maxwell Air Force Base

During the 1940s, Parks worked as a seamstress at Maxwell Air Force Base (AFB) in Montgomery, Alabama. Her husband Raymond also worked on the base as a barber. Although other parts of Montgomery were racially segregated, President Truman issued an executive order in 1948 that desegregated the military. As a result, the federal government prohibited the separation of white and Black people on the base. At Maxwell AFB, Rosa Parks could ride on an integrated trolley. But on her way home, she had to ride on a segregated city bus. “You might just say Maxwell opened my eyes up,” she wrote in her memoir. “It was an alternative reality to the ugly policies of Jim Crow.”

Although the base was not officially segregated, the Parkses still encountered discrimination and racism. After the Montgomery bus boycott began in 1955, many white customers stopped supporting Raymond’s barbershop; some even made rude and offensive remarks about Rosa. Authorities at Maxwell AFB eventually banned any mention of her or the bus boycott at the shop. Nevertheless, the discrimination continued, and Raymond Parks quit his job.

Maxwell Air Force Base Senior Officers' Quarters Historic District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1988.

Photo by ajay_suresh. CC BY 2.0.

2. Hotel Theresa

During Parks’s first year with the Montgomery NAACP, she had gathered accounts of racially motivated crimes throughout Alabama, including sexual assaults, police brutality, and unsolved murders. In the autumn of 1944, the Montgomery NAACP dispatched Parks to investigate the violent abduction and sexual assault of Mrs. Recy Taylor.

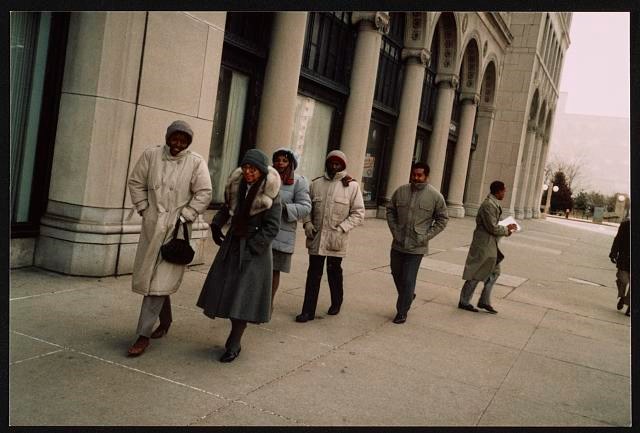

African Americans across the country demanded justice and Parks quickly gathered the support of local activists, labor unions, African American organizations, and women’s groups to form the Alabama Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor.On November 25, 1944, activists called an emergency meeting to order at the Hotel Theresa in Harlem, New York City. The Hotel Theresa was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2005. The meeting was organized to bring national attention to Taylor’s case and demand legal action. To make up for inaction by state authorities, the Committee for Equal Justice for Mrs. Recy Taylor transformed from a local organization into a national one. The committee kicked off a massive public campaign to demand that Alabama’s governor, Chauncey Sparks, launch an investigation into Taylor’s assault with hopes of indicting the attackers. Committee members flooded his office with letters, postcards, and petitions. Although their campaign was unsuccessful, these tactics prepared Parks for later activism in her career.

Courtesy Library of Congress.

3. Historic Ebenezer Baptist Church Heritage Sanctuary

In August 1955, Parks participated in a two-week desegregation workshop at the Highlander Folk School. Founded by Myles Horton and Don West in 1932, the school offered interracial training sessions for labor and civil rights activists. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Eleanor Roosevelt, and Septima Poinsette Clark also attended workshops at the school. Clark became the School’s Director of Workshops and led the session that Parks attended. Years after completing the program, Parks remarked, “That was the first time in my life I had lived in an atmosphere of complete equality with the members of the other race.”

Clark also offered other programs throughout the South to increase adult literacy and civics education among African Americans. Her Citizenship Schools laid the groundwork for the Citizenship Education Program within the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The SCLC was founded at Ebenezer Baptist Church in January 1957. The Historic Ebenezer Baptist Church Heritage Sanctuary is a property within the Martin Luther King National Historical Park. Although Parks attended Clark’s workshop at the Highlander Folk School, she later spoke at the Ebenezer Baptist Church on the first anniversary of Dr. King’s birthday after his assassination.

Photo by punkairwaves, CC BY-SA 4.0.

4. Dexter Avenue Baptist Church

During the summer of 1955, fourteen-year-old, Chicago-native Emmett Till visited family in Money, Mississippi. On August 28, he was accused of whistling at a white woman. That night, the woman’s husband and brother-in-law kidnapped Till and brutally murdered him. One month later, an all-white jury acquitted Till’s murderers. Outrage erupted over the verdict around the world.

On November 27, Rosa Parks attended a rally at Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where the activist Dr. T. R. M. Howard spoke about Till’s life and death. The Dexter Avenue Baptist Church was listed in the National Register of Historic Places and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1974. Howard’s speech stuck with Parks in the coming months and inspired one of the most lauded moments of the civil rights movement. On December 1, nearly one hundred days after Till’s murder, Parks refused to give up her seat on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama. Her actions launched the start of the Montgomery bus boycott. Years later, civil rights leader Jesse Jackson asked Parks why she refused to move. She replied, “I thought of Emmett Till and I couldn’t go back.”

Photo by Quinn Evans Architects, courtesy of Michigan State Historic Preservation Office.

5. Rosa and Raymond Parks Flat

In 1957, Parks moved with her husband and mother to join her brother Sylvester in Detroit. After the move, Detroit became the new center of Parks’s activism as well as her home until her death in 2005. Rosa and Raymond Parks Flat in Detroit was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 2021. During the 1960s, Parks ventured out of Detroit to participate in the March on Washington and the Selma to Montgomery March. While living in Detroit, she wrote several books, including her autobiography and supported various causes including women’s rights, the Black Power movement, and the Poor People’s Campaign. In 1987, she established the Rosa and Raymond Parks Institute for Self-Development. The Institute supported civil rights education for young people in Detroit.

Courtesy Library of Congress.

6. General Motors Building

In 1986, General Motors announced its plan to close five automotive plants in Michigan. Because the closures would lay off thousands of local workers, Parks joined Congressman John Conyers, Jr. to protest. They picketed outside of the company’s headquarters in Detroit. Now known as Cadillac Place, the General Motors Building was listed in National Register of Historic Places and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1978.Parks first met Conyers in 1964 when she volunteered for his campaign for the U.S. House of Representatives. When Conyers was elected to Congress in 1965, he invited Parks to join his staff as a receptionist and administrative assistant. She held this position until her retirement in 1988.

Bibliography

Culbert, Alexa. “Maxwell and the Civil Rights Movement.” Maxwell Airforce Base. Published February 24, 2015. https://www.maxwell.af.mil/News/Display/Article/704338/maxwell-and-the-civil-rights-movement/.

Digital SNCC Gateway. “Highlander Folk School.” Alliances & Relationships. Inside SNCC. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://snccdigital.org/inside-sncc/alliances-relationships/highlander/.

Library of Congress. Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words. Exhibition. Opened December 5, 2019. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/rosa-parks-in-her-own-words/about-this-exhibition/#explore-the-exhibit.

Interview with Rosa Parks, conducted by Blackside, Inc. on November 14, 1985, for Eyes on the Prize: America's Civil Rights Years (1954-1965). Washington University Libraries, Film and Media Archive, Henry Hampton Collection. http://digital.wustl.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=eop;cc=eop;rgn=main;view= text;idno=par0015.0895.080.

Tags

- women's history

- african american history

- african american heritage

- african american women

- civil rights

- civil rights movement

- labor history

- women in the labor movement

- detroit

- michigan

- alabama

- montgomery bus boycott

- naacp

- emmett till

- labor movement

- social movements

- african american civil rights

- places of article

- places of...