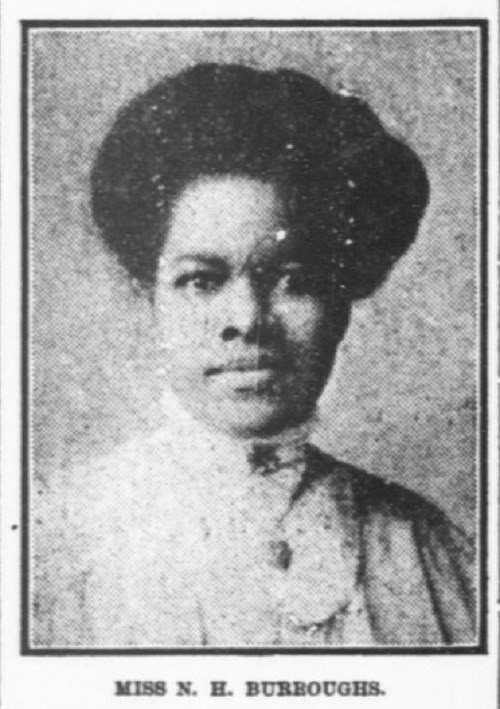

Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Nannie Helen Burroughs .

Article

Places of Nannie Helen Burroughs

Inquiry Question:

What makes someone an effective leader? What qualities do you possess that make you a leader?

Introduction:

Nannie Helen Burroughs was born in the late 1870s or early 1880s to a formerly enslaved couple living in Orange, Virginia. After her father died, she and her mother relocated to Washington, DC where she attended M Street High School (now Paul Laurence Dunbar High School). After graduation, Burroughs moved around to find work. From 1898 to 1909, Burroughs worked for the National Baptist Convention’s (NBC) Foreign Mission Board in Louisville, Kentucky. Even after she left Kentucky, she continued her involvement with the NBC. She even established a Women’s Auxiliary to help support the organization’s mission. This group gave women members of the NBC more freedom to organize their own events, hold conferences, and more. Burroughs served in leadership capacity from 1900 to 1947.

After returning to the DC area, Burroughs founded her own school, the National Training School for Women and Girls, to educate African American women. She served as an educator and principal of the school.

Burroughs also advocated for greater civil rights for African Americans and women. At the time, Black women had few career choices. Many did domestic work like cooking and cleaning. Burroughs believed women should have the opportunity to receive an education and job training. She wrote about the need for Black and white women to work together to achieve the right to vote.

Learn about some of the places associated with her life and work.

M Street High School (Washington, DC)

After the Civil War (1861-1865), Black Americans moved to Washington, DC from both the South and the North seeking employment, education, and an opportunity to participate in government.1 Between 1860 and 1870, Washington’s African American population grew more than that of any other city in America.2 The capital city needed more education institutions for African Americans.

Founded in 1870, the M Street High School was one of the first Black schools in the US established with public funds. Classes were held in different locations during the school’s early years. In 1890, when Congress appropriated $112,000 in funds, the school was able to establish a permanent location at 128 M Street N.W.3

Prompted by the death of her father, Nannie Helen Burroughs and her mother moved to the nation’s capital to live with family. She attended high school at the M Street School where she studied under activists like Anna Julia Cooper. Her teachers inspired her to challenge racism and sexism, and she eventually dedicated her life to fighting for suffrage and civil rights. Burroughs graduated M Street High School with honors in 1894.4

M Street High School was listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1986.

National Training School for Women and Girls

Burroughs struggled to find work after graduating from M Street High School. She moved to Philadelphia and then Louisville, Kentucky for work. She eventually returned to Washington in the hopes of establishing her own school for Black girls.

The NBC and the Women’s Auxiliary group helped raise funds to purchase six acres of land in northeast Washington. Burroughs also needed money to construct the school. She did not, however, have unanimous support about the kinds of classes the school should offer. Civil rights leader Booker T. Washington did not believe African Americans would donate money to fund the school. But Burroughs did not want to depend on money from wealthy white donors. Relying on small donations from Black women and children from the community, Burroughs managed to raise enough money to open the school.

Even though some people disagreed with teaching women skills other than domestic work, the school was popular in the first half of the 20th century. At the time, Black women had few career choices. Many did domestic work like cooking and cleaning. Burroughs believed women should have the opportunity to receive an education and job training. The school originally operated out of a small farm house. In 1928, a larger building named Trades Hall was constructed. The hall housed twelve classrooms, three offices, an assembly area and a print shop.

The school, renamed the Nannie Helen Burroughs School in her honor, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1991.

Logan’s Circle Historic District (Washington, DC)

Burroughs was involved in a number of organizations and causes including the Women’s Auxiliary of the NBC, the National Association of Colored Women (NACW) and more. She also founded the National League of Republican Colored Women. This organization became more popular after the passage and ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. As head of the organization, Burroughs encouraged Black women to exercise their newly recognized right to vote. The group’s headquarters was based at 1115 Rhode Island Ave NW, in the Logan’s Circle Historic District of Washington. In a correspondence to the group, Burroughs wrote:

“Since Negro women have the ballot, they must not under-value it…The Race is doomed unless Negro women take an active part in local, state, and national politics.“6

The Logan’s Circle area was ideal for Burrough’s National League of Republican Colored Women. In the early 1900s, many middle and upper-class Black families lived in the Victorian row houses surrounding Logan’s Circle. The area attracted a number of African American writers, artists and educators including Alain Leroy Locke and the Grimke family. Educator and civil rights activist Mary McLeod Bethune even purchased a house here which became the headquarters of the National Council of Negro Women.

The Logan’s Circle Historic District was listed in the National Register of Historic Places 1974.

Constitution Hall (Washington, DC)

In December 1931, the White House Conference of Home Building and Ownership convened at Constitution Hall in Washington,. In front of a crowd of 3,000, President Herbert Hoover announced the creation of special committees to address the housing crisis in the US following the onset of the Great Depression. One of the committees was dedication to addressing housing for African Americans. Hoover selected Burroughs to serve as the committee chair. Her appointment to this position exemplifies her dedication to advancing human rights for all people. Burroughs understood that access to education, affordable housing, living wages, voting rights, and civil rights were interconnected issues.

Constitution Hall was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1985.

Conclusion:

Though her involvement with the early Black civil rights movement and women’s suffrage movement, Burroughs became a well-known figure in Black communities nation-wide. She laid the groundwork for the modern Black civil rights movement and even mentored leaders like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. She continued her activism until her death in 1961.

1 Kate Masur, An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C., (The University of North California, 2010), 7.

2 Ibid, 28.

3 M Street High School National Register nomination, https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/c3449d06-85a3-4b61-b06f-8fd3b9b1bbc9.

4 Ann Michele Mason, Nannie Helen Burroughs’ Rhetorical Leadership During the Inter-War Period, University of Maryland, dissertation, (2008).

5 “Ratification and Beyond,” Library of Congress digital exhibit, https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/women-fight-for-the-vote/about-this-exhibition/hear-us-roar-victory-1918-and-beyond/ratification-and-beyond/race-is-doomed-unless-negro-women-take-an-active-part/

Bibliography

Coker, Kathryn. “African American Educator and Activist: Nannie Helen Burroughs.” Richmond Public Library, https://rvalibrary.org/shelf-respect/history-and-preservation/african-american-educator-and-activist-nannie-helen-burroughs/.

Johnson, Charles S. Report of the Committee on Negro Housing. Washington, DC, 1932. https://archive.org/stream/negrohousingrepo00presrich/negrohousingrepo00presrich_djvu.txt

Mason, Ann Michele. Nannie Helen Burroughs’ Rhetorical Leadership During the Inter-War Period. University of Maryland. Dissertation, 2008.

Masur, Kate. An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C. The University of North California, 2010.

“Address to the White House Conference on Home Building and Home Ownership.” The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-the-white-house-conference-home-building-and-home-ownership.

Logan’s Circle Historic District National Register nomination, https://npgallery.nps.gov/GetAsset/67ec8354-4349-4c73-9072-2a1cd3f3ee18.

M Street High School National Register nomination, https://npgallery.nps.gov/NRHP/GetAsset/c3449d06-85a3-4b61-b06f-8fd3b9b1bbc9.

“Ratification and Beyond,” Library of Congress digital exhibit, https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/women-fight-for-the-vote/about-this-exhibition/hear-us-roar-victory-1918-and-beyond/ratification-and-beyond/race-is-doomed-unless-negro-women-take-an-active-part/

Tags

- women’s history

- women’s rights

- women’s suffrage

- suffrage

- 19th amendment

- african american history

- african american sites

- african american women

- national register of historic places

- national historic landmark

- washington d.c.

- washington dc

- art and education

- education

- places of...

- places of article

- educator

- civil rights

- civil rights movement

Last updated: August 5, 2021