Part of a series of articles titled Of Poetry and Nature: Longfellow's Green Rhyme and Verse.

Article

Longfellow's Environmental Niche

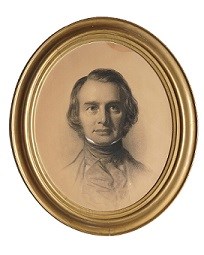

Museum Collection, Longfellow House - Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 544)

One of the foremost poets of the 1800s, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote a wide array of prose and poetry dedicated to the natural world. Despite this, he is not as well-known for his nature writing as his contemporaries Walt Whitman or Emily Dickinson are today.

Among 21st century literary critics and academics, Longfellow’s nature writing is often dismissed as pretty lyrics lacking intrigue. Closer inspection of Longfellow’s personal and professional life, however, shows how entrenched Longfellow was in the fast-evolving state of environmental thought in the mid-1800s.

Longfellow both pulled from and contributed to this movement of art and philosophy. Although he was not championing new movements like his friend Ralph Waldo Emerson, Longfellow can be considered, as biographer Charles C. Calhoun says, “an environmentalist before his time.” 1

How did Longfellow’s relationship to nature shape his and others’ work?

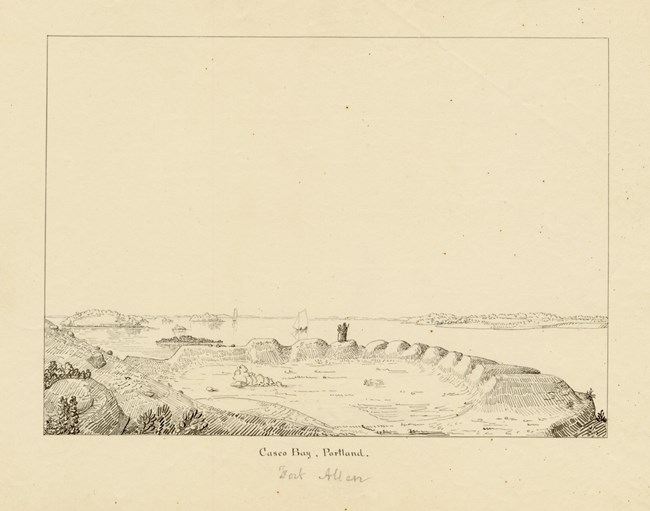

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 19322)

A Childhood and Education of Romantic Nature

Longfellow’s admiration for the natural world likely bore its roots early in his childhood.

Born to Zilpah and Stephen Longfellow in Portland, Maine, Longfellow relished in the seaside views of the estate established by his grandfather, a proud descendant of passengers on the Mayflower and a veteran of the Revolutionary War.

He remembers the Portland of his childhood with fondness and vivacity, later penning in his 1858 poem “My Lost Youth”:

I can see the shadowy lines of its trees,

And catch, in sudden gleams,

The sheen of the far-surrounding seas,

And islands that were the Hesperides

Of all my boyish dreams.I remember the black wharves and the slips,

And the sea-tides tossing free;

And Spanish sailors with bearded lips,

And the beauty and mystery of the ships,

And the magic of the sea.

In these stanzas, Longfellow writes in a Romantic tradition, celebrating the landscape for both its natural and human elements, even invoking the Hesperides, the “Daughters of the Evening” or “Nymphs of the West” of Greek myth. His literary sensibilities were well-informed early in his life as young Longfellow was undoubtedly reading Romantic poetry from the 1700s.

According to Calhoun, “much of his real education, of course, took place in his father’s library, which was small but well stocked in the classics of British literature, as filtered by eighteenth-century taste.”2 In this library—among other big names like Milton and Shakespeare—were several writers who were producing early Romantic works about the natural world that may have also influenced Longfellow’s sentimentality for nature so prolific in his poetry. Oliver Goldsmith, for instance, wrote his famous poem “The Deserted Village,” in which a rural village, once an ideal picture of pastoral life, is ultimately deserted because of the haste in urban development. Other poets available to the young Longfellow, like James Thomson and Alexander Pope, both write on similar themes celebrating rural life in their poem collections The Seasons (1726-1730) and Pastorals (1709), respectively.

Longfellow continued this reading into his formal education. In fact, in one recorded exchange between a sixteen-year-old Longfellow, away education at Bowdoin College in Brunswick, and his mother, Longfellow lauded the 18th-century poet Thomas Gray’s odes.3 Gray was a poet of widespread critical acclaim but few published poems, most known for his poem “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.” In “Elegy” and other poems like “Ode to Spring,” Gray emphasizes the picturesque, linking his inner thoughts with features of the landscape and place. According to a young Longfellow, Gray’s work dealt in a “sublimity” that was foreign to him, but he was nonetheless “very pleased” with the poems.

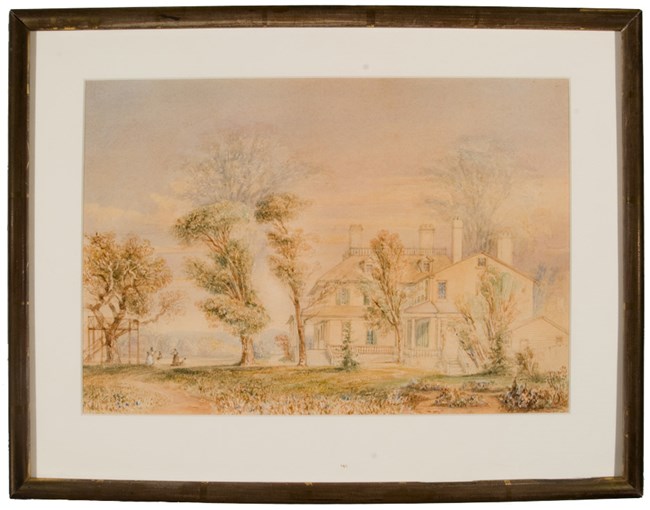

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 4861)

Longfellow was reading contemporaries to Gray, too, although written evidence of this can be found nearly a decade later. In August 1836, Longfellow recounted a day of vacation in Switzerland to his journal: “time glided too swiftly away. We read the ‘Genevieve’ of Coleridge, and the ‘Christabel,’ and many scraps of song.”4 More evidence of Longfellow's admiration for Coleridge can be found among Longfellow’s personal book collection: a copy of Coleridge's most famous narrative ballad “Rime of the Ancient Mariner” (1798), annotated in Longfellow's own hand.5 Coleridge was a key figure in the English Romantic movement; along with fellow Romanic poet William Wordsworth, Coleridge dedicated much of his work to experimenting with form and content, emphasizing the integral bridge between people and the natural world in many of his poems. Coleridge's "Rime," in which a sailor kills an albatross out of his own pride, dooming the ship’s entire crew, can be read as a parable for the consequences of disrespecting nature, and Longfellow’s narrative poem “Wreck of Hesperus” (1842) employs similar themes.

The young poet was also exposed to poets of American Romanticism, such as William Cullen Bryant. At the time Longfellow was publishing his first notable poems prior to his graduation from Bowdoin, William Cullen Bryant was America’s most renowned poet and journalist. In August 1825, Bryant, the long-time editor for New-York Evening Post, praised the then-unknown Longfellow’s poems (“Sunrise on the Hills,” “An April Day,” “Hymn of the Moravian Nuns”) years before meeting Longfellow formally in Germany.6 By then, Longfellow’s career would be on the steady incline, and the national landscape that Bryant wrote about in his most acclaimed poems, like “Thanatopsis,” “Green River,” and “To a Waterfowl” of the late 1700s looked very different. While Bryant’s poems celebrated nature for its intrinsic spiritual value, his poetry also was in anticipation of the Industrialization to follow.

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 7325)

A Green Social Orbit

With Industrialization reshaping literary thought Longfellow found himself in orbit of new philosophies. Ralph Waldo Emerson, for instance, was a good friend of Longfellow who regularly visited the Harvard professor at Craigie Castle. It was also in Boston that Emerson founded Transcendentalism, a literary and philosophical movement branching off from Romanticism. The movement upheld “back to nature” principles, but took it a step further by dismissing modernity, arguing that innate truths and morals were found within the human spirit and natural world, waiting to be learned collectively.10

Emerson pioneered this movement, explaining how nature was a sublime force of power and goodwill. In his essay “Nature” 1836, of which Longfellow received a new edition of in 1849,11 Emerson writes, “In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life—no disgrace, no calamity (leaving me my eyes) which nature cannot repair.”12

Although Longfellow did not subscribe to Transcendentalism, he entertained many other peers who did, like the writer W. Ellery Channing and Emerson’s mentee Henry David Thoreau, who both attended a dinner party hosted by Longfellow as noted in his journal on November 23, 1848.13 This is not to say that Longfellow didn’t admire some of the works in this literary circle; in a later journal entry on June 29th 1849, Longfellow references “Thoreau's account of his one night in Concord jail,” now known as his essay “Civil Disobedience,” stating that it was “extremely good.”14 And, over their years of companionship, Longfellow attended many of Emerson’s lectures and recorded his attendance in his journal several times between 1838 and 1871, albeit receiving some of them better than others (Of Emerson’s lecture on Holiness, Longfellow said: “Not exactly comprehending it (and who does?) they seem to be sitting in the shadow of some awful atheism or other.”).15

Rounding out this social circle of Transcendentalists were several scientists who nurtured Longfellow's interest in natural history through correspondences and lectures. One such scientist was Asa Gray, a colleague to Charles Darwin and the most renowned American botanist during the time. After attending one of Gray's botany lectures, Longfellow noted in his journal: "What a wide sweep the subject has; and how poetical!".16 There are several recorded exchanges beween the two discussing an excitement for plants, but Longfellow was even closer to Swiss-born American naturalist Louis Agassiz, who moved to Cambridge after accepting a professor position at Harvard in 1847.17 Among his peers, Agassiz drew widespread criticism for his creationist views and support of scientific racism, ultimately leading to his discreditation in the broader scientific community. Agassiz pioneered many scientific methods and techniques for collecting biological information about anything from the local rock formations to native organisms.

Longfellow was quietly among those who did not agree with his friend’s beliefs but admired the biologist for his lectures in geology and specimens he studied. Among a sarcastic critique of Agassiz’s evolutionary theory beliefs,18 his journals keep detailed records of his interactions with Agassiz, once taking his young son Erny to see Agassiz’s “odd fishes in alcohol, a new species from California” in April 185419 and Fanny to see the “three hundred fossil teeth” and “great Medusa [jellyfish] in a bathing tub” in August 1858.20

Most telling, perhaps, is Longfellow’s journal entry written on February 4th, 1847: “I heard Agassiz extolling my description of the glacier of the Rhone in ‘Hyperion;’ which is pleasant in the mouth of a Swiss, who has a glacial theory of his own.”21 Even in this interaction, which occurred early in their friendship, their respect for each other’s intellect is mutual; Agassiz has read Hyperion, despite its disappointing critical reception, and Longfellow cares to know that his writing on the natural features in his fictional book is accurate.

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 4395)

A Reciprocal Relationship with the Arts

Despite his friendship with a professor of science, Longfellow’s interest in natural history was more casual than academic. He seemed to most value the aesthetics the natural world lent to art, in both written and visual mediums. For instance, Longfellow was a staunch admirer of the burgeoning landscape art movement in mid-1800s New England, the Hudson River School. This group of painters were known for their sweeping American landscapes that idealized nature and portrayed the relationship between nature and man as one of peace and balance, also contributing to the ongoing conservation movement. Longfellow saw many of these paintings firsthand; on July 27th, 1849, after visiting an art gallery by Thomas Cole, the appointed founder of the Hudson River School movement, Longfellow recorded his thoughts in his journal: “the air of Art was wafted about me and I had a delicious feeling on the old galleries come over me as I looked dreamily upon the heads and landscapes.”22

Longfellow attended lectures by painters (Henry Augustus Ferguson’s 1865 lecture, according to Longfellow’s journal, had “beautiful bits of landscape”23) and was personally acquainted with many prominent Hudson River School painters, often introduced to him through mutual friends. Longfellow's brother-in-law Thomas Gold Appleton was a key link to many of Longfellow's connections in the art world; while Longfellow was more a casual collector, Appleton was an ardent patron of the arts, steeped in a vast social circle of artists and served on the board of trustees managing art for the Boston Public Library and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Through Appleton, Longfellow first met John F. Kensett, a painter known for the use of light in his landscapes, in January of 1855, deeming him an “agreeable young gentleman of very prepossessing manners.”24 Three years later in May 1858, he would again mention in his journal socializing with Kensett, this time joined by a younger landscape painter Winckworth Allan Gay,25 with whom he would cross paths again in 1866.26

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 4138)

Hiawatha would inspire the illustrations and paintings of another prominent American landscape painter, Thomas Moran, who wrote to the poet to express his desire to meet Longfellow and show his own art inspired by the poet's work in 1867.27

As prominent landscape artists, both Moran and Bierstadt were especially attuned to power of a landscape—real or fictional—to convey humans’ communal relationship with nature; their use of Longfellow’s poem as a source for their art proves that the poet succeeded in crafting an environment that reflected such a relationship.

Museum Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 4439)

A Local Steward

Beyond the arts, he concerned himself with much of the local greenery on his estate. At the newly acquired Craigie Castle, Longfellow was witnessing the urbanization of the 1800s in real time: the development of Cambridge from rural to suburban. As the surrounding landscape changed, what was once large open fields, meadows, and orchards became commercial and residential lots. In the house, Longfellow worked and wrote many of his poems with a view of the Charles River dotted with passing boats--a scene reminiscent of his Portland childhood. A staunch admirer of the house’s history, Longfellow regarded the elm trees in the yard to be living witnesses to George Washington’s stay at the estate, instructing the gardeners to protect them.

His daughter, Alice Longfellow, also reflected on her father’s investment and care in the estate’s greenspace, recalling that her father “was much interested in planting new trees and shrubs and in laying out an old-fashioned garden. The plan of the somewhat elaborate flower beds was his own design, surrounded by low borders of box, and filled with a variety of flowers. He was not a botanist nor a student of flowers, but he found a little amateur landscape gardening a very agreeable pastime.”28

Longfellow valued the greenspace in the neighborhood, too. In 1868, upon hearing that slaughterhouses were slated for potential construction on the marshes on the other side of the Charles River in Brighton, threatening the view from the house, Longfellow rallied funds and support from his friends to purchase the land. Ultimately, Longfellow donated the meadows to Harvard to be used as a public greenspace for the community to enjoy even today.29

Buildings and Grounds Photograph Collection, Longfellow House-Washington's Headquarters NHS (3008/2.1#2)

As he did with his hometown Portland, Longfellow took to verse to express his admiration for the Charles River. Written in 1842, the resulting poem is an ode entitled “To the River Charles,” directly addressing the neighboring waters. The poem gives insight to Longfellow’s quick mobilization to protect the meadows around the river:

Thou hast taught me, Silent River!

Many a lesson, deep and long;

Thou hast been a generous giver;

I can give thee but a song.Oft in sadness and in illness,

I have watched thy current glide,

Till the beauty of its stillness

Overflowed me, like a tide.

Longfellow writes this poem as a gift of gratitude to the river, whom he considers a “generous” teacher. Even so, he admits that he knows that he can never reciprocate in full, as he laments to the river that he can “give thee but a song.” One can imagine, then, Longfellow sitting in his study, watching the “current glide, / Till the beauty of its stillness overflowed [him] like a tide,” and hoping that preserving the meadow along the its banks was as much a gift to the river as it was to him.

His love of nature is apparent through the authors and thinkers he read, the friends he kept, the art he collected, and the garden he tended--but how did he convey this love through the rhyme and verse of his poetry?

-Pauline Ordonez, 2021

- Charles Calhoun, Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life (Boston: Beacon Press, 2004), pg. 135.

- Calhoun, Longfellow, pg. 23.

- Nicholas A. Basbanes, Cross of Snow: A Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2020), pg. 22.

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, August 1836

- Though the inscribed volume was described in 1887, the book is not in the museum collection today. A newspaper account described, “After the lines ‘The naked hulk alongside came, And the twain were casting dice: "'The game is done! I've won. I've won!" Quoth she, and whistles thrice,' Longfellow’s annotation reads: 'To be struck out. S.T.C.': 'A gust of wind started up behind, And whistled through his bones; Through the holes of his eyes and the hole of his mouth, Half whistles and half groans.’ W.M. Fullerton, "In Craigie House: An Hour In Longfellow's Study," Boston Daily Advertiser (1887), quoted in Sarah H. Heald, The Longfellow House: Historical Furnishings Report (National Park Service, 1999) vol 1, p 218.

- Nicholas A. Basbanes, Cross of Snow: A Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2020), pg. 25.

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1835), pg 12.

- William Cronon, “The Trouble With Wilderness; or, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature” (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1995).

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, July 18, 1836.

- Russell Goodman, "Transcendentalism," The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2019).

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 10 September 1849.

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nature (Boston: James Munroe and Company, 1849), pg. 8.

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 23 November 1848.

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 29 June 1849.

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 28 April 1838.

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 21 November 1849.

- Nicholas A. Basbanes, Cross of Snow: A Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2020), pg. 295.

- “To tea came Kah-ge-ga-gah'-bowh, the Ojibway Chief, and we went together to hear Agassiz lecture on the 'Races of Men.' He thinks there were several Adams and Eves and several gardens of Eden.” HWL Journal, May 13, 1850.

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 24 April 1854.

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 25 August 1858.

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 4 February 1847.

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 27 July 1849.

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 8 March 1865.

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 31 January 1855.

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 14 May 1858.

- Journal, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, 17 February 1866.

- Nicholas A. Basbanes, Cross of Snow: A Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2020), pg. 370.

- Alice Longfellow, Reminiscences of My Father quoted in Catherine Evans, Cultural Landscape Report for Longfellow National Historic Site (Boston: National Park Service, 1993), vol 1, pg. 44.

- Catherine Evans, Cultural Landscape Report for Longfellow National Historic Site (Boston: National Park Service, 1993), vol 1, pg. 48.

Last updated: October 29, 2021