Part of a series of articles titled Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Authors of the United States.

Article

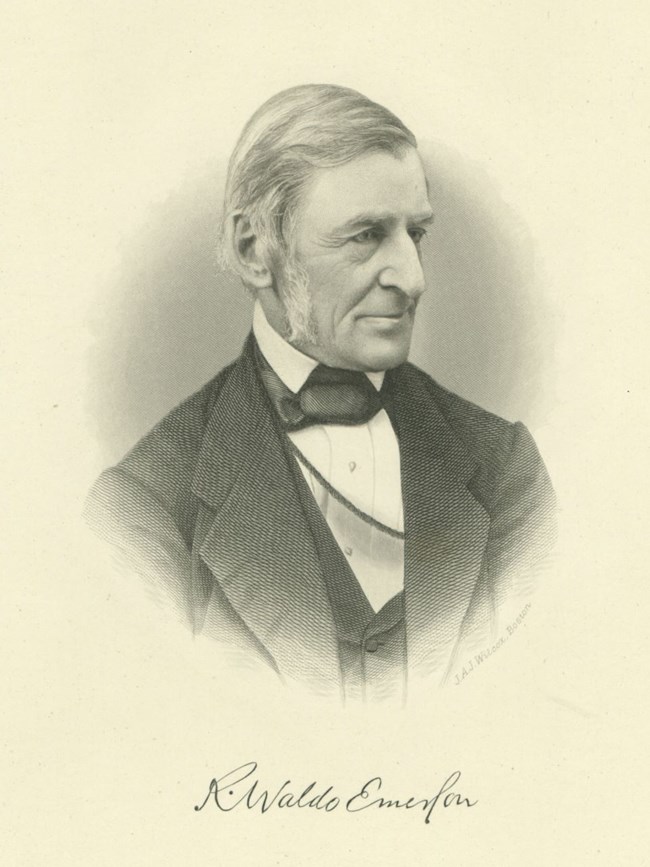

Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Ralph Waldo Emerson

Museum Collection, Longfellow House - Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 4795)

The story is often repeated that, at Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s funeral in March 1882, an aging Ralph Waldo Emerson paid his respects at the poet’s casket twice, apparently forgetting he had already done so. After Longfellow’s burial at Mount Auburn Cemetery, at which Emerson was present, he turned to his daughter Ellen and said, “The gentleman we have just been burying was a sweet and beautiful soul; but I forget his name.”1

Literary historian Newton Arvin used the incident as an indication that Longfellow’s reputation (or, symbolically, his name) was buried along with his body. In fact, the scene is more indicative of a somewhat undiscussed aspect of the life of Ralph Waldo Emerson: later in life he experienced some form of dementia, likely Alzheimer’s. A philosopher whose brilliance earned an international reputation, Emerson died only about a month after Longfellow’s burial. Both were honored in meetings of and a publication by the Massachusetts Historical Society.2 The personal copy of Tributes to Longfellow and Emerson by the Massachusetts Historical Society once owned by Samuel Longfellow remains in the National Park Service’s collection today.3

The coincidental timing of the deaths of these two authors naturally led to comparisons of their legacies. In 1884, Longfellow became the first American honored with a memorial bust in Westminster Abbey’s Poets Corner; Emerson's supporters argued he would have been a more appropriate choice for this precedent.4 Almost exact contemporaries, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807-1882) and Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) each made significant contributions to the blossoming of American literature in the nineteenth century and maintained a lifelong friendship.

Emerson and Longfellow Crossing Paths

Emerson and Longfellow were contemporaries who shared connections to Harvard and rising popularity as major literary figures in New England. Their paths crossed early; in 1833, Longfellow met Thomas Carlyle in Europe thanks to a letter of introduction from Emerson, with whom Carlyle would remain a frequent correspondent.5 It is unknown how Longfellow acquired this letter from Emerson.

In his lifetime, Emerson was particularly well known as a lecturer (an activity that Longfellow refused to join outside of the classroom). Longfellow heard Emerson speak in 1838 and wrote in his journal for March 8, “This evening Emerson lectured on the Affections; a good lecture. He mistakes his power somewhat, and at times speaks in oracles, darkly. He is vastly more of a poet than a philosopher. He has a brilliant mind and develops and expands an idea very beautifully, and with abundant similitudes and illustrations.” He then recounted a quote from Jeremiah Mason, a former U.S. Senator and retired lawyer, who was asked if he could understand Emerson and answered, “No, I can’t, but my daughters can.”6

Longfellow had moved to Cambridge not long before the first unofficial meeting of the Transcendental Club was held in that city on September 8, 1836; the first official meeting was held just over a week later in Boston.7 Emerson was a founding member of this group of religious leaders who came to question the tenets and practices of their religion. This movement became known as Transcendentalism and Emerson was soon its figurehead. Eventually, the club would include other important members with whom Longfellow was acquainted: Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, George Ripley, Bronson Alcott, James Freeman Clarke, Christopher Pearse Cranch, and many others.

It is often forgotten, however, that Emerson was extremely controversial in his early Transcendentalist years. His Harvard “Divinity School Address” (1838) dismissed Biblical miracles and questioned Jesus’s equivalency with God (he had resigned from his Boston ministry because of similar questions of faith practice). The speech resulted in his unofficial banishment from his alma mater for 30 years.8 In a letter to his father, Longfellow referenced the printed version of this speech and its subsequent rebuttal from theologian Andrews Norton: “By the way, Mr. Emerson’s sermon before the Theological class, which created such a sensation, has been published. I will send you a copy. A critique upon it, by Mr. Norton, has appeared in the Daily Advertiser, with answer and rejoinder. You will see this controversy in your paper. This is the newest matter on foot, and the most talked about.”9 Even in 1860, Mrs. Longfellow noted that Emerson’s lectures were “very racy.”10 Theologian Orestes Brownson warned that Transcendentalism was “the dominant error of our times.”11

Earlier, Fanny Longfellow, then still Fanny Appleton, was also in Emerson’s circle. in January 1842, shortly before her marriage to Henry Longfellow, she had attended a party and teasingly noted: “I had an amusing peep at the Transcendental strata.” As she recalled: “Miss [Margaret] Fuller and Emerson sat like old philosophers in the groves, each with a swarm of disciples as a halo.” She also noted that she and Emerson danced – or, as she said, “scuffled.”12

Museum Collection, Longfellow House - Washington's Headquarters NHS (LONG 541)

Nevertheless, Emerson eventually became a friend of Longfellow and his family. By 1846, a portrait of Emerson by Eastman Johnson (along with others of Cornelius Conway Felton, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Charles Sumner) graced his study. They even spent time together on vacation in Nahant.13 Despite his comments that Emerson could not be understood, Longfellow attended several of his lectures over the years. In October 1838, Longfellow wrote to a friend that “in this quarter of the world, lecturing is the fashion” and that, among others, he has heard Emerson, “a clergyman,” speak. He called him, “One of the finest lecturers I ever heard, with magnificent passages of true prose-poetry. But it is all dreamery, after all.”14 He also heard Emerson’s lecture on “Great Men” at the Odeon in 1845, and referred to its “many striking and brilliant passages, but not so much as usual of that ‘sweet rhetoricke’ which usually flows from his lips” and added that Emerson, as always, offered “many things to shock the sensitive ear and heart.”15

Emerson circulated a petition to pass a copyright law, which Longfellow signed in May 1852.16 Throughout the 1840s and 1850s, the two men frequently saw one another on visits to Concord or Cambridge (or at the homes of mutual friends) and at lectures. Emerson may have even spent the night at the Longfellows’ Brattle Street home.17 The two would continue a fairly vigorous correspondence throughout their lives.

The Civil War and Social Clubs

Both Emerson and Longfellow took public stances on slavery; Longfellow in 1842 in his Poems on Slavery, and Emerson, with hesitation, included it in lectures particularly beginning in 1840s. Emerson was particularly bothered by the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which required citizens and officials to assist in the recapture of enslaved people who escaped bondage. Instead, he proclaimed, “I will not obey it, by God!” Emerson was quick to bring up the political climate in conversation – something which the more reserved Longfellow clearly lamented. In 1856, for example, Longfellow records dining with Emerson and Louis Agassiz, among others. “I was amused and annoyed to see how soon the conversation drifted off into politics. It was not till after dinner, in the library, that we got upon anything really interesting.”18

Though he also was angered by the Fugitive Slave Act, Longfellow’s antislavery beliefs were more private and he did not speak publicly on the topic.19 He did, however, support Emerson’s speech against the Fugitive Slave Act in 1851 at Cambridge City Hall. He called it “grand” but disliked Emerson’s negative comments on Senator Daniel Webster, who had helped create the bill. Some did not agree with Emerson that night and Longfellow noted, “It is rather painful to see Emerson in the arena of politics, hissed and hooted at by young law-students.”20 Still, Longfellow was disappointed that Boston was caught up in the same Fugitive Slave law that Emerson hated. When the freedom seeker Anthony Burns was captured in Boston, Longfellow wrote in his journal, “O city without soul! When and where will this end? Shame, that the great Republic, the ‘refuge of the oppressed,’ should stoop so low as to become the Hunter of Slaves!”21

Both supported John Brown, an abolitionist who led a high-profile raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry in 1859, to different degrees. Emerson gave speeches honoring his actions to bring about a slave insurrection, even calling him “that new saint” whose death by execution for treason “will make the gallows glorious like the cross.”22 Longfellow equally saw Brown as a martyr and wrote in his journal not long after Emerson’s speech:

The second of December 1859. This will be a great day in our history; the date of a new Revolution, – quite as much needed as the old one. Even now as I write, they are leading old John Brown to execution in Virginia for attempting to rescue slaves! This is sowing the wind to reap the whirlwind, which will come soon.23

When the Civil War broke out, Emerson hoped that President Abraham Lincoln would focus on the freedom of enslaved people more than preserving the Union. Famously, in 1862, Emerson proclaimed in a public speech, “The South calls slavery an institution... I call it destitution.”24 He met Lincoln through Longfellow’s good friend, Senator Charles Sumner.

As the War came to its conclusion, both Longfellow and Emerson resumed their domestic interests (as did the rest of the country). The two men joined social clubs in the Boston area, including the group that founded the Atlantic Monthly with both men as contributors. They were also both active members of the Saturday Club which met monthly at the Parker House hotel in Boston. They also served as pallbearers for the funeral of their friend Nathaniel Hawthorne in 1864, after which Longfellow apparently visited Emerson’s house.25

In the years following the Civil War, the two authors - then among the most elite of American writers - regularly exchanged copies of their new works. Longfellow gave Emerson a copy of Tales of a Wayside Inn in1864, to which Emerson responded gratefully.26 Emerson gave Longfellow an inscribed copy “with old regards” of his Prose Works in October 1869.27 Emerson later included the poem “The Birds of Killingworth” from Tales of a Wayside Inn in his anthology (1880), as well as Longfellow’s “The Children’s Hour,” “The Warden of the Cinque Ports,” “The Cumberland,” “Santa Filomena,” “The Fiftieth Birthday of Agassiz,” and an excerpt from “A Psalm of Life.” Longfellow called it a “welcome gift of Song” and “an excellent collection.”28 His copy of Parnassus remains in the collection today.29 Longfellow, in turn, included several poems by Emerson in his 1878 multivolume collection Poems of Places, (some of which were truncated), including “The Snow-Storm,” “Boston,” “Musketaquid,” “Two Rivers,” and “Monadnock.”

Poetry and Philosophy

Though Longfellow and Emerson are often considered members of the Fireside Poetry movement (creators of “safe” poetry that garnered a popular audience), Emerson was mostly a writer of lectures and essays; his poetry, then and now, remains less famous and less important (one major exception being his “Boston Hymn,” which includes the now well-known line about “the shot heard ‘round the world”). Longfellow said, however, that Emerson was more “poet than philosopher,” likely as a jab at Emerson’s incomprehensibility despite sounding impressive. Emerson’s most important contribution to literature, perhaps, is his call for American writers and American scholars, definitions he combined into one identity.

In fact, much of Emerson’s famous 1837 speech in Cambridge “The American Scholar” echoes what Longfellow himself had said in his Bowdoin College commencement oration years earlier: the ability to improve American literature hinged on true poets focusing on their craft. Emerson even considered Longfellow’s Kavanagh to be “the best sketch we have seen in the direction of the American Novel.” Predicting the thoughts of John William de Forest by 20 years in his essay on “The Great American Novel,” Emerson also praised Longfellow’s book for showing “our native speech and manners, treated with sympathy taste, and judgment.”30

Nevertheless, how the two address “true” poetry was very different. Emerson, always a theologian and thinker, wrote about Nature (with a capital “N”) and the relationship between humanity and the deity – which, in turn, was seen through Nature. Though Longfellow was no stranger to spiritual questions in his verses, his concern was more on the sentiments of humanity and the people themselves. While Emerson was writing his ode to “The Humble-Bee,” Longfellow was elevating “The Village Blacksmith” into a topic worthy of poetry. The two both wrote with moral message but, as one early biography of Longfellow noted, “Morality to Emerson was the very breath of existence; to Longfellow it was a sentiment.”31 Longfellow appreciated Emerson’s poetry enough on include his poem “Each in All” in his early anonymous anthology The Waif (1845). Longfellow had originally asked to use “The Problem.”32

Emerson, who had significant wealth thanks to a well-paying ministerial job and particularly after an inheritance from his first wife after her death, believed in simplicity. His Concord home, still standing and operating as a museum, was a symbol of modesty and stands in marked contrast to the Cambridge home of his friend Longfellow. In his journal, he wrote of his friend Henry David Thoreau, who felt a foreboding in the extravagance he saw at the Brattle Street home: “If Socrates were here, we could go & talk with him; but Longfellow, we cannot go & talk with; there is a palace, & servants, & a row of bottles of different coloured wines, & wine glasses, and fine coats.”33 This opulence was, perhaps, too much for Emerson as well, who was concerned about the “one more rock” placed between man and “his true ends.”34

Emerson also offered passing judgments on Longfellow’s style of poetry which may appear somewhat passive aggressive. When Longfellow sent his friend a copy of his Song of Hiawatha in November 1855, Emerson responded with a thank you note. In it, he wrote, “I have always one foremost satisfaction in reading your books that I am safe – I am in variously skilful hands but first of all they are safe hands.” Nevertheless, he enjoyed the book and its presentation of Native Americans, “sweet & wholesome as maize very proper and pertinent to us to read, & showing a kind of manly sense of duty in the poet to write.” Emerson also noted, however, that he thought Native Americans were savage and had “poor small sterile heads” with “no thoughts.”35 One wonders, then, what Emerson had in mind when, at the end of 1849, he wrote to Longfellow looking for an excuse to see him “to talk, one of these days, of poetry, of which, when I read your verse, I think I have something to say to you.”36

Longfellow, in turn, enjoyed Emerson’s poetry, but also sometimes found them as challenging as his lectures. In 1846, he had “the keenest pleasure” reading Emerson’s poems, for example, but found some to be “Sphinx-like.” He did, however, find here and there “veins of purest poetry, like rivers running through meadows,” though they had to be found “through the golden mist and sublimation of fancy gleam.”37 He even joined many others in referring to Emerson as the “sage of Concord.”38 Overall, if his 1846 journal entry can be trusted, Longfellow had a positive view of Emerson: “We like Emerson, – his beautiful voice, deep thought, and mild melody of language.”39 The two, however, were never significantly close friends. To many, Emerson seemed aloof and incapable of intimate relationships (John Matteson, biographer of Emerson’s friend Margaret Fuller, noted that Emerson’s “coldness of manner” was due to the several losses in his life which resulted in his difficulty to “form permanent relationships”).40 Fanny Longfellow remarked in July 1849, “I never feel he cares, from his heart, for any human being.”41

Was Longfellow a Transcendentalist?

Emerson, like Transcendentalism in general, was and remains notoriously difficult to comprehend. Longfellow’s future wife, then Fanny Appleton, joked about the incomprehensibility of the group’s official magazine The Dial: “This last number [e.g. issue] is ‘beyond beyond’ for absurdity; some verses by Emerson on the Sphynx which you would think could only have been written in Bedlam.”42 Longfellow did not disagree; in 1838, he referred to one of Emerson’s lectures as “a great bugbear” that his listeners likely did not understand, adding “and who does?”43

Longfellow said little about Transcendentalism at a time when many Bostonians were remarking either for it or against it outright. One early biographer saw this lack of commentary as a sign of “his thorough caution and sagacity” and, ultimately, he was “little affected” by it.44 Transcendentalism being a religious movement, at least initially, also ensured Longfellow would leave behind little evidence of his response to it. As his brother wrote in his memoir, “He [Longfellow] did not care to talk much on theological points; but he believed in the supremacy of good in the world and in the universe.”45 Transcendentalism had similar beliefs about goodness, and Longfellow recognized Emerson, the poet-philosopher, as a religious leader in a movement about goodness and nature. In 1849, for example, he wrote in his journal about hearing Emerson:

Emerson is like a beautiful portico, in a lovely scene of nature. We stand expectant, waiting for the High-Priest to come forth; and lo, there comes a gentle wind from the portal, swelling and subsiding; and the blossoms and the vine-leaves shake, and far away down the green fields the grasses bend and wave; and we ask, " When will the High-Priest come forth and reveal to us the truth?" and the disciples say, "He has already gone forth, and is yonder in the meadows." "And the truth he was to reveal?" "It is Nature; nothing more."46

Some of Longfellow’s works were compared favorably with works by the Transcendentalists. James Russell Lowell, for example, associated Longfellow’s Kavanagh: A Tale (one of Longfellow's only major prose works) and Sylvester Judd’s Margaret (perhaps the only significant Transcendentalist novel).47 Emerson also praised Kavanagh. Longfellow was influenced by many of the same European thinkers and literary figures that inspired Transcendentalism.48 Like Emerson and others, he also considered William Ellery Channing one of the most important religious reformers, even going so far as to dedicate his 1842 book Poems on Slavery to him. Most Transcendentalists, however, were theologians, religious leaders, or philosophers. Longfellow was none of these things and he never attended a meeting of the Transcendentalist Club. Longfellow, then, was not a Transcendentalist.

Ultimately, Transcendentalism as a movement was relatively brief and relatively small. However, its influence on other intellectual and religious movements and individuals, including Longfellow’s brother, the Reverend Samuel Longfellow, endured.49

The works of Emerson and Longfellow have also endured. While their reputations have shifted over time, their writings and complex relationship shaped the 19th century literary landscape and still resonates in the 21st.

Notes

Quotations from Henry Longfellow's journal are from Samuel Longfellow, ed., Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Boston: Ticknor and Company, 1886), cited below as Life.

1. Newton Arvin, Longfellow: His Life and Work (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1963), 295. The quote appears in several variations. Charles Calhoun in his book Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life recorded Emerson’s words as “I cannot recall the name of our friend, but he was a good man.”

2. See Tributes to Longfellow and Emerson by The Massachusetts Historical Society (Boston: A. Williams and Co., 1882).

3. LONG 16303

4. See “Literary Miscellany,” The Literary News, Volume III, No. 10 (October 1882), 313.

5. Charles Calhoun, Longfellow: A Rediscovered Life (Boston: Beacon Press, 2004), 100.

6. Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, March 8, 1838, quoted in Life, Volume I, 277.

7. Barbara L. Packer, The Transcendentalists (Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 2007), 47.

8. Wilson Sullivan, New England Men of Letters (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1972), 14.

9. Letter, Henry W. Longfellow to his Stephen Longfellow, September 2, 1838, quoted in Life, Volume I, 295.

10. Letter, Fanny Longfellow to Thomas Gold Appleton, December 10, 1860, in the Frances Elizabeth Appleton Longfellow (1817-1861) Papers, 1825-1961 (LONG 20257), Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters NHS.

11. Philip F. Gura, American Transcendentalism: A History. New York: Hill and Wang, 1997: 198.

12. Letter, Fanny Appleton to Emmeline Austin, January 2, 1842, quoted in Edward Wagenknecht, ed. Mrs. Longfellow: Selected Journals and Letters of Fanny Appleton Longfellow (New York: Longmans, Green and Co., 1956), 81

13. See Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, August 31, 1851, quoted in Life, Volume II: 201.

14. Letter, Henry W. Longfellow to George Washington Greene, October 22, 1838, quoted in Life, Volume I, 301.

15. Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, December 11, 1845, quoted in Life, Volume II: 27.

16. Letter, Henry W. Longfellow to Ralph Waldo Emerson, May 26, 1852, quoted in Andrew Hilen, ed., The Letters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972) Volume III, 345-346.

17. At least an invitation was offered. Letter, Henry W. Longfellow to Ralph Waldo Emerson, November 28, [1845]. Andrew Hilen, ed., The Letters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1972), Volume III, 91.

18. Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, April 3, 1856, quoted in Life, Volume II, 276.

19. See, for example, his responses to the captures of Thomas Simms. Life, Volume II, 192-193, etc.

20. quoted in Life, Volume II: 194-195.

21. Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, April 4, 1851, quoted in Life, Volume II, 193-194.

22. Quoted in David S. Reynolds, John Brown, Abolitionist: The Man Who Killed Slavery, Sparked the Civil War, and Seeded Civil Rights (Vintage Books, 2005), 366.

23. Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, quoted in Life, Volume II, 347.

24. Carlos Baker, Emerson Among the Eccentrics: A Group Portrait (New York: Viking Press, 1996), 433.

25. See Letter, Henry W. Longfellow to Charles Sumner, May 23, 1864, quoted in Life, Volume II, 407.

26. See Letter, Ralph Waldo Emerson to Henry W. Longfellow, February 24, 1864, quoted in Life, Volume II, 402.

27. LONG 27925-6

28. Letter, Henry W. Longfellow to Ralph Waldo Emerson, January 24, 1876, qhoted in Eleanor Marguerite Tilton, ed., The Letters of Ralph Waldo Emerson (The Ralph Waldo Emerson Memorial Association, 1929), Volume 6, 268.

29. LONG 15703. Signed “Henry W. Longfellow / 1875”

30. Letter, Ralph Waldo Emerson to Henry W. Longfellow, May 24, 1849, quoted in Life, Volume II, 140.

31. Erich S. Robertson, Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (London: Walter Scott, 1887), 174.

32. Letter, Henry W. Longfellow to Ralph Waldo Emerson, November 25, [1846], quoted in Andrew Hilen, ed., The Letters of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (Harvard University Press, 1972), Volume III, 124.

33. Newton Arvin, Longfellow: His Life and Work (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1963), 52.

34. It is unclear here, but it seems Emerson is quoting Thoreau. Emerson’s journals are seldom dated but this entry is likely from 1853, about a year before Thoreau published Walden. See and Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks: 1852-1855 (Harvard University Press, 1977), Volume XIII, 38.

35. Letter, Ralph Waldo Emerson to Henry W. Longfellow, November 25, 1855. Joel Myerson, ed., The Selected Letters of Ralph Waldo Emerson (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), 386.

36. Letter, Ralph Waldo Emerson to Henry W. Longfellow, December 30, 1849, quoted in Life, Volume II, 154.

37. Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, December 26, 1846, quoted in Life, Volume II, 69.

38. See Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, June 16, 1854, quoted in Life, Volume II, 247.

39. Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, February 4, 1846, quoted in Life, Volume II, 32.

40. John Matteson, The Lives of Margaret Fuller: A Biography (New York: W. W. Norton, 2012), 182.

41. Letter, Fanny Longellow to Charles Sumner, July 1849, in the Frances Elizabeth Appleton Longfellow (1817-1861) Papers, 1825-1961 (LONG 20257), Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters NHS.

42. Letter, Fanny Appleton to Isaac Appleton Jewett, January 25, 1841, in the Frances Elizabeth Appleton Longfellow (1817-1861) Papers, 1825-1961 (LONG 20257), Longfellow House-Washington’s Headquarters NHS.

43. Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, March 28, 1838, quoted in Robert L. Gale, A Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Companion (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003), 68.

44. Erich S. Robertson, Life of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (London: Walter Scott, 1887), 99.

45. Life, Volume I, 14.

46. Journal, Henry W. Longfellow, January 29, 1849, quoted in Life, Volume II, 132.

47. Philip F. Gura, American Transcendentalism: A History (New York: Hill and Wang, 1997), 197-198.

48. Tiffany Wayne, Encyclopedia of Transcendentalism (New York: Facts on File, 2006), 169.

49. Philip F. Gura, American Transcendentalism: A History (New York: Hill and Wang, 1997), 8.

Last updated: March 24, 2023