Part of a series of articles titled Education Inequalities in World War II.

Article

Lesson 2: Education Inequalities in California Schools during World War II

BreiAunna. "Children Statue." Wikicommons, April 2023.

Introduction:

Before Brown v. Board of Education, another court case declared that “separate was not equal” in schools. For decades, the California school systems segregated Latino, especially Mexican American, students into separate schools. This was common in the 1940s when Gonzalo and Felicitas Mendez tried to enroll their children in Westminster Public Schools. Denied entry because of their Mexican heritage, the Mendez family challenged the decision. Their case went to the US Court of Appeals.

This lesson is based on articles from Entangled Inequalities. Students will think about how Mexican American families challenged discrimination before and during World War II. It can be taught as part of a unit on World War II, Mexican American History, or Civil Rights in the United States. It is the second in a series of three lessons about discrimination and education during World War II. You may teach it individually or as part of that series. You can find more lessons at Teaching with Historic Places.

Lesson Objectives

Students will be able to:

-

Identify ways in which Mexican American students were discriminated against in California and other states in the American Southwest.

-

Corroborate multiple sources and perspectives to gain a better historical understanding.

-

Apply the Fourteenth Amendment of the US Constitution to school segregation.

Essential Question

What does it mean to have access to an equal education?

Warm Up: First Day

When Sylvia Mendez’s Aunt went to take her, her brothers and cousins to their first day of classes, they were already doing something new that can be scary. Remember your first day of school. How did you feel? What did you do to prepare? What made the first day a good or a not good one?

Duke University, 1944.

Background Reading:

To learn more, visit Entangled Inequalities: Setting the Precedent: Mendez, et al v Westminster.

For the first sixty years of United States history, what is now the state of California was part of Mexico. Mexico ceded the land to the United States after the Mexican-American War in 1848 and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Yet, there were thousands of Mexicans living in that territory. They suddenly became “Mexican American” but were still considered foreigners by many Anglo Americans. After the war, Mexicans continued to immigrate to the Southwest looking for jobs or a better life. The US government often encouraged this migration. There was a lot of discrimination in California and other parts of the US against Latino families.

One of the places where Mexican Americans faced discrimination was in schools. By the early 1900s, there were separate schools for children of Mexican descent. They particularly targeted students who didn’t speak a lot of English or were thought to be "too brown." In the 1940s, 80% of students of Mexican heritage in California went to separate schools. These schools were run down, often using books or furniture that white schools had discarded. More stark was the difference in the curriculum. Instead of focusing on academic subjects, Mexican schools taught English--whether they needed it or not--and work skills.

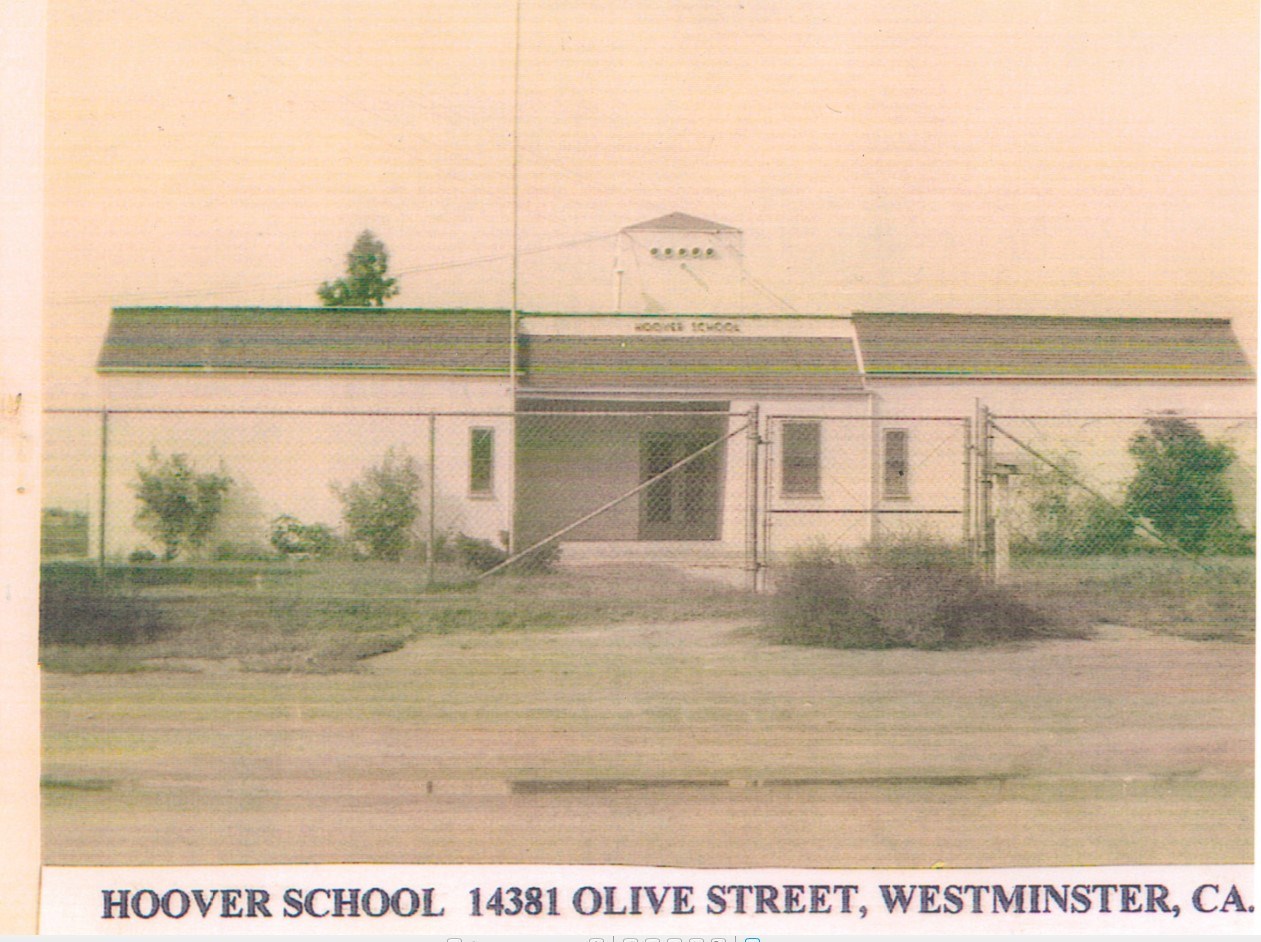

The Mendezes were one of the families that faced this discrimination. Unable to buy land, it was typical for Mexican families to lease their land or work as tenant farmers. Gonzalo Mendez leased land from the Munemitsu family, who were forcibly detained in Japanese Incarceration camps in 1943. His sister, Soledad “Sally” Vidaurri, look both families’ children to enroll in the same local school the Munemitsu children had attended. The school allowed Aunt Sally's children to enter because they were lighter skinned with a French last name. School officials sent Sylvia Mendez and her brothers to Hoover School for Mexican students.

When Gonzalo and Felicitas Mendez went to appeal the decision, the school rejected their claim. With the help of LULAC (the League of United Latin American Citizens) and other Civil Rights organizations, the Mendez family brought a federal lawsuit against the school district, which was appealed all the way to the US Court of Appeals.

PBS LearningMedia. © 2004, 2005 WGBH Educational Foundation. All rights reserved.

Activity 1: Corroborating School Conditions

Watch and read the following sources. As you do, think about what each one tells you about the conditions in schools for Mexican children and how they might be different from the white schools.

Source 1:

Documenting Brown 4: Mendez v. Westminster | PBS LearningMedia

Watch the video from the beginning to 3:58.

Source 2:

“Social Emphasis has been laid upon the use of spoken and written English, reading, writing, spelling, the most practical use of numbers, sewing and mending for the girls, and manual training for the boys, better habits of living for both. The manual training for the boys has taken varied lines of activity, such as carpentry, repairing shoes, basketry, hair cutting, and blacksmithing.”

-

Superintendent J.A. Cranston of Santa Ana School District, July 8 1913. Quoted in Gilbert Gonzalez. “Segregation of Mexican Children in a Southern California City: The Legacy of Expansionism in the American Southwest.”

Source 3:

“We weren’t taught to be smart. We were taught how to be maids and how to crochet and how to quilt.”

Sylvia Mendez

Source 4:

"Hoover School." Frank Mt. Pleasant Library of Special Collections and Archives. Chapman University, Digital Commons.

Discussion Questions:

- What are two or three details that stand out to you about schools for Mexican American students?

- How would you compare the schools for white students and the schools for Mexican American students in California?

- Were Mexican American students being given an equal opportunity to get a good education? Use evidence from at least two sources to support your answer.

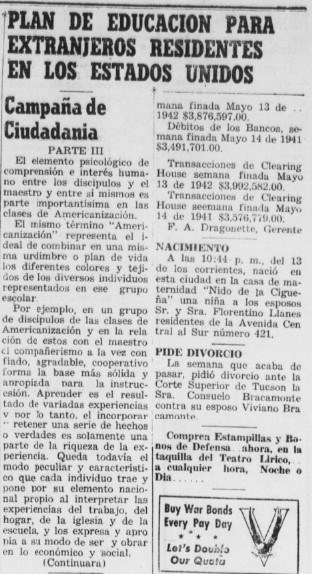

El Tucsonense. May 19, 1942. Tucson Arizona. Courtesy of the University of Arizona Digital Library Collection.

Activity 2: Americanization and the War

The Mendezes were in Westminster, California because of World War II. They were leasing the Munemitsus’ land while the government incarcerated people of Japanese descent. The War changed or brought to the surface a lot of discussions and debates about what it meant to be an American. Although school segregation had been happening in California for fifty years, a new emphasis on Americanization classes was happening throughout the country. Americanization classes were promoted in both English and Spanish speaking communities.

Read the newspaper article from 1942 below then answer the questions.

Teacher Tip: The article has been transcribed in both the original Spanish and in English. This may be an opportunity to talk about bilingualism and the fact that there is no official language in the United States. You can also encourage any students who speak or are learning Spanish to read the Spanish version first.

Plan de Educación para extranjeros residentes en los estados unidos

Campana de Ciudadanía

El elemento psicológico de comprensión e interés humano entre los discípulos y el maestro y entre sí mismos es parte importantísima en las clases de Americanización.

El mismo término “Americanización” representa el ideal de combinar en una misma urdimbre o plan de vida los diferentes colores y tejidos de los diversos individuos representados en ese grupo escolar.

Por ejemplo, en un grupo de discípulos de las clases de Americanización y en la relación de estos con el maestro, el compañerismo a la vez confiado agradable, cooperativo, forma la base más sólida y apropiada para la instrucción. Aprender es el resultado de variadas experiencias y por lo tanto, el incorporar y retener una serie de hechos o verdades es solamente una parte de la riqueza de la experiencia. Queda todavía el modo peculiar y característico que cada individuo trae y pone por su elemento nacional propio al interpretar las experiencias del trabajo, del hogar, de la iglesia y de la escuela, y los expresa y apropia a sa modo de ser y obrar en lo económico y social…

Education plan for foreign residents in the United States

Citizenship Campaign

Elements of understanding and human connection between students and teacher is a very important part of Americanization classes. Also true between the students themselves.

The term “Americanization” represents the ideal fabric. These are threads woven from the colors and fabrics of the different people represented in that school group.

For example, within a group of students in the Americanization classes, relationships are trusting, agreeable, and cooperative. It should be the same with the teacher. These bonds form the most solid and appropriate foundation for instruction. Learning is the result of varied experiences. Therefore, memorizing a series of facts or truths is only part of the richness of the experience. Each individual brings unique characteristics from his own national perspective. He expresses them when interpreting his experiences at work, home, church and school. Then, he appropriates them to his way of being and acting in the economy and in society…

Questions

-

What is “Americanization” according to this article? What is the purpose of the Americanization classes?

-

Why, according to the article, are these classes successful?

-

Why do you think an article like this might run during World War II?

-

How does this support and/or contradict what you have learned about segregated schools for Mexican Americans in states like California? How do you think Sylvia and her family might feel about this characterization of schools for Mexican Americans?

Activity 3: Applying the Fourteenth Amendment

The Mendez' lawsuit was based on the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution. The Fourteenth Amendment was passed after the Civil War. Read the text of the Amendment and think about how it applies to schools in the 1940s and students of all racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Fourteenth Amendment:

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Analysis Questions:

-

What does the Fourteenth Amendment promise? Who does it promise it to?

-

How might this apply to Sylvia Mendez and her family’s desire to go to their local public school?

-

School officials in Westminster California, like many leaders in the American South discussing school segregation against African Americans, argued that the facilities were “separate but equal,” and therefore fair under the Fourteenth Amendment. Do you agree? Why or why not?

History Connection: The term “separate but equal” comes from the Supreme Court Case Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). The case was about the rights of African Americans to ride the same train cars as white Americans. The Court ruled that separation based on race did not suggest that one race was inferior. The majority also made a difference between political equality and other forms of equality. It is from this case that the term and precedent “separate but equal” came from. What do you think has changed since the 1890s?

Wikimedia Commons. 2018.

Exit Activity:

Teacher Tip: You can collect this exit ticket in whichever way best suits your classroom. This may be a chance for students to share with each other, by posting to your classroom online forum or sticky notes on the wall to facilitate conversation next class. You can also have them submit, on an index card or a private online assignment, for you to check for understanding.

How would you characterize Mexican Americans’ school experience during World War II? How do you feel this experience fits with messages and promises of the United States generally and during the War specifically?

Additional Resources:

Explore the Library of Congress’ Resource Guide for Mendez v. Westminster. It includes a video from author Duncan Tonatiuh, reading from his children’s book “Separate is Never Equal.”

Check out the US District Court of Southern California where Mendez v Westminster was decided, which is a National Historic Landmark in Los Angeles, CA.

Examine original court documents from Mendez v. Westminster from the National Archives of the United States.

This article was written by Alison Russell, an Educator and Consulting Historian with the Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education. It was funded by the National Council on Public History’s cooperative agreement with the National Park Service.

References:

Sadlier, Sarah. “Mendez v. Westminster. The Harbinger of Brown v Board of Education.” Ezra’s Archives, 76-89.

Mendez et al. V. Westminster School District of Orange County et al. Civil Action No. 4292. United States District Court for the Southern District of California, Central Division. February 18, 1946. From PBS Learning Media.

Tags

- entangled inequalities

- latino

- latino history

- latino heritage

- american latino history

- american latino heritage

- mexican american

- mexican american history

- puerto rican

- civil rights

- legal history

- arts culture and education

- education

- school desegregation

- westminster

- spanish

- orange county

- los angeles

- california

- lesson plan

- lesson

- teaching with historic places

- twhp

- twhplp

- education inequalities

- world war ii

- ww2

- wwii

- world war ii home front

Last updated: February 20, 2024