Part of a series of articles titled Education Inequalities in World War II.

Article

Entangled Inequalities: Japanese Incarceration and Mendez, et al. v. Westminster School District of Orange County, et al.

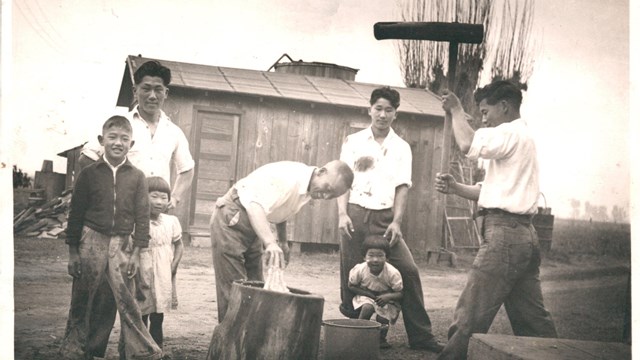

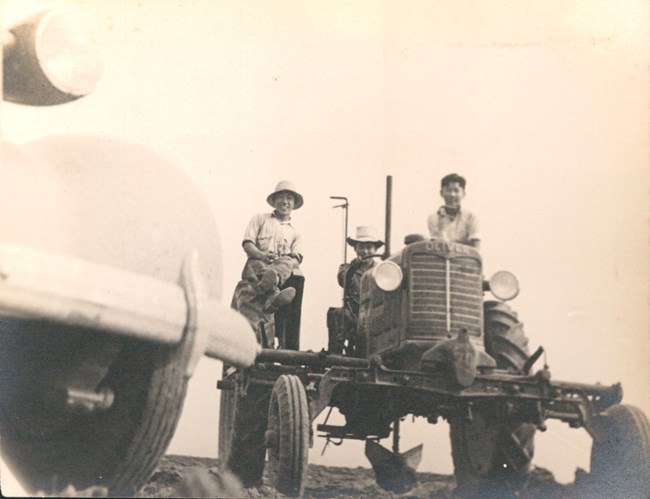

Courtesy of Janice Munemitsu and Chapman University.

Introduction

In 1947, the Mendez, Guzman, Palomino, Estrada and Ramirez families won the legal battle in US federal court to end racial segregation in public schools. Known as Mendez, et al. v. Westminster School District of Orange County, et al., this case preceded Brown v. Board of Education by 7 years, the US Supreme Court case that declared racial segregation in schools unconstitutional in 1954.

This story starts with two (extra)ordinary families who made southern California their home. During World War II, 125,000 Japanese Americans were forced to evacuate from their homes into incarceration camps. Seventy percent of the Japanese Americans were born US citizens; the rest included their immigrant parents who were legal residents of the US. Among those 125,000 was the Munemitsu family. They left everything behind and leased their family farm to the Mendez family with the hope that one day they would come back. The Mendez family made the farm their new home, moving from Santa Ana, CA to Westminster, CA, a distance of less than 10 miles. When they tried to enroll their children into the local school, they were denied admission. Because they were Mexican American children, they were forced to go to the “Mexican” school.

“Racism by the government and school districts denied both families of their constitutional amendment freedoms and rights, but acts of kindness along the way created the path to justice.” - Janice Munemitsu, author of The Kindness of Color and daughter of Tad Munemitsu

This project explores the entangled inequalities that brought the two families together. It also highlights some of the people and historic places that can speak to their story.

The Families

This series introduces the Munemitsu family and shares some of their experiences with migration and Japanese American incarceration.

Learn about the Mendez family's courageous fight for education equality in California and some of the forces that shaped their story.

Places Connections

Courtesy of Janice Munemitsu and Chapman University.

The Munemitsu Farm

The Munemitsu family farm was a forty-acre property located on Edwards Street in Westminster, California. Initially the land was leased by Seima Munemitsu and owned by an elderly woman. When she died, she gave the Munemitsus the first chance at putting in an offer for the property. Unfortunately, due to the California Alien Land Law of 1913, Seima was not able to bid on the property as he was not a citizen of the US. The law also blocked him from becoming a naturalized citizen. Instead, his son Tad—a US citizen who was a minor at the time—became the owner of the farm.

On the farm property was the farmhouse, four workers cottages, a packing house for packing produce, a barn, and two outhouses which shared a wall. After purchasing the property, Seima built two ofuros, Japanese soaking tubs. Typically, in addition to the Munemitsu family, there would be up to fourteen braceros living on the farm at any given time. Braceros are Mexican laborers allowed into the US for a limited time to do agricultural work. The braceros would live in the four workers' cottages using one of the two outhouses. Food for both the family and the braceros would be made by the mother of the family, whichever family was there at the time.

When the Munemitsu family was forced to leave their farm, their banker and friend Frank Monroe, advised them to try to lease the farm and secure it for the future when the war ended. Monroe introduced the Munemitsus to Gonzalo Mendez, who had grown up working in the area as a farm hand and had always wanted to run his own farm. It was leased to Gonzalo Mendez as “move-in ready,” with all the necessary tools and equipment and the crops already planted. The main crop at this time was asparagus.

Tad’s daughter Janice Munemitsu found lease documents from December 1944, with a second one from August 1945 to August 1946. No one is certain if prior lease documents were lost or if another “handshake” arrangement was made between 1942 and December 1944. Under the conditions of the lease, the Mendez family could live on and work the farm, selling what they grew for profit. They would also pay rent to the Munemitsu family, so both families would benefit from this lease.

Today, the location of the Munemitsu family farm is occupied by two public schools: Johnson Intermediate and Finley Elementary Schools. Both are a part of the Westminster School District.

Collection of the National Archives and Records Administration (NAID: 536153)

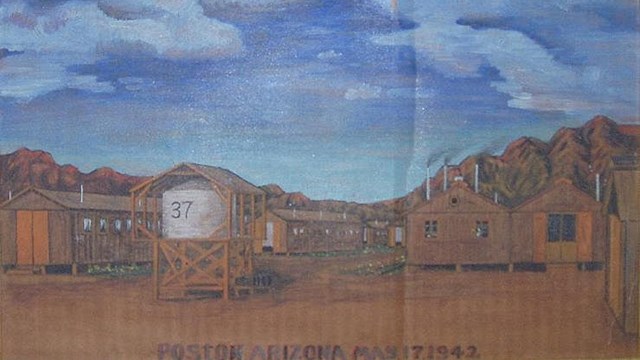

Poston War Relocation Center

Between May 1942 and September 1945, the Munemitsu family (except Seima) was incarcerated at Poston Relocation Center in present-day La Paz County, Arizona. Poston was one of ten major War Relocation Authority (WRA) detention centers located throughout the interior of the United States. Before Tule Lake, Poston initially detained the largest number of Japanese Americans. With a peak population of 17,814, the incarceration of Japanese Americans made Poston the third largest community in Arizona, behind Phoenix and Tucson.

Poston was officially named the “Colorado River Relocation Center.” It was built on 71,000 acres of the Colorado River Indian Reservation despite opposition from the Tribal Council. The Tribal Council viewed Japanese American incarceration as an injustice and rejected plans to put the camp on the reservation, but the US government overruled them. When construction was complete, the WRA and Office of Indian Affairs (OIA) jointly managed Poston for its first eighteen months of operation.

The site was organized into three military detention center camps known as Poston Camp 1, Camp 2, and Camp 3. The inmates called them “Roasten,” “Toasten,” and “Dustin” in reference to the extreme climate of the Sonoran Desert. In addition to administrative buildings and housing for staff and army guards, Poston included rows of barracks and other facilities where Japanese American incarcerees lived and worked. These included a community store, mess hall, hospital, and schools. Most Japanese Americans remember the lack of any privacy in the communal open latrine, open shower, and barrack living quarters.

Photo by MikeJiroch, Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0.

US Courthouse & Post Office

Before Brown v. Board of Education made racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, there was Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, et al. This 1946 class-action lawsuit challenged the constitutionality of separate schools for Mexican American students in Southern California and eventually helped end public school segregation across the state. The trial took place at the US District Court of Southern California, on the second floor of the US Court House & Post Office building, a National Historic Landmark, in Los Angeles. Built in 1940, this historic building was only five years old during Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, et al.

More to Explore

Education and learning did not stop for those detained within incarceration camps, but both students and teachers faced unique challenges.

Discover how incarcerated youth used art to reimagine Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, et. al. as a mural for justice.

Bring the Munemitsu and Mendez family stories into the classroom with this lesson series about education inequalities during World War II.

Additional People

The Mendez and Munemitsu families are at the heart of this story, but there were many others who also played a role. Learn about some of them here.

Frank Monroe was a white banker at the First Western Bank of Garden Grove. Monroe was also a friend to many of his customers, including Gonzalo Mendez and Seima and Tad Munemitsu. When Tad was about eight years old, Monroe became a mentor to him, teaching him about banking and business as Tad translated between English and Japanese for his Issei father. Tad’s connection with Monroe continued into adulthood as a lifelong customer at the bank and family friend to Monroe and his wife.

When Executive Order 9066 forced the Munemitsus to relocate into incarceration camps in May 1942, Monroe also helped the family to lease their farm, farmhouses, and equipment to Gonzalo Mendez. By leasing the farm in 1944, Mendez was able to fulfill his dream to become a farmer, not just a farmworker. The lease also ensured that the Munemitsus did not have to lose the farm or sell it under value while they were incarcerated.

David C. Marcus was a Jewish American attorney who represented the Mendez family in their initial lawsuit against Westminster School District. Marcus spoke fluent Spanish and worked for the Mexican Consulate. In 1944, he won a lawsuit against the city of San Bernardino, California, challenging the exclusion of Mexican Americans from the community’s sole park and swimming pool.

In Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, et al., Marcus introduced a new argument with the backing of a sociologist and education expert. He argued that segregating Mexican and Mexican American students based on their nationality or ethnic background resulted in feelings of inferiority that harmed their education. He highlighted negative impacts to their ability to learn English and “American customs and ways.”

Marcus’s own experiences with antisemitism informed his approach to civil rights issues. As the father of Mexican American children, the stakes were even more personal. Marcus’s second wife (Maria) Yrma Davila had immigrated from Mexico City. In the pre-trial hearing for Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, et al., he acknowledged that although his own children experienced educational privilege, discrimination was still pervasive in the education system.

“The fact is that where segregation is a general pattern, it is an instrument to enforce inequality.” - Thurgood Marshall, Robert L. Carter, and Loren Miller, “Brief for the National Association of Colored People as amicus curiae,” Westminster v. Mendez, 161 F2d. 774 (9th Cir. 1947), 11.

Thurgood Marshall, Robert L. Carter, and Loren Miller were African American attorneys for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). While awaiting the decision in Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, et al., several organizations wrote briefs to the Court of Appeals on behalf of Mendez and other Mexican Americans. Writing for the NAACP, Marshall, Carter, and Miller argued that school segregation was unconstitutional. To illustrate that the facilities were separate but not equal, they emphasized how segregation negatively impacted Mexican American students. Their brief in Mendez, et al., v. Westminster, et. al., became the basis for their argument against the segregation of Black students in the US Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

During Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, et al., Earl Warren served as the governor of California. In June 1947, he signed the Anderson Bill, which repealed the remaining sections of the California Education Code that permitted segregation. This legislation preceded the US Supreme Court case, Brown v. Board of Education by seven years. By the time Brown reached the US Supreme Court in 1954, Warren had been appointed the court’s chief justice. He wrote the unanimous majority opinion in Brown, which ended public school segregation based on race throughout the US.

Conclusion: The Mendez-Munemitsu Legacy

The Munemitsu family’s story is preserved and remembered in various ways, including documentaries and books. Tad Munemitsu’s daughter, Janice Munemitsu, has become a keeper of the Munemitsu family story. She is the author of The Kindness of Color (2021), which connects the relationship between the Munemitsu and Mendez families through archival materials and family history. Janice Munemitsu and Sylvia Mendez both carry and preserve the legacy of their intertwined stories. In December 2020, the City of Westminster dedicated the Mendez Tribute Park, which includes educational panels created by the Orange County Board of Education.

While often discussed in isolation, Japanese incarceration and school segregation unfolded concurrently within the Mendez and Munemitsu story. Their story offers a precursor to the fight for civil rights and against school desegregation in the 1950s and 1960s. The injustices the Munemitsu and Mendez families faced are situated amidst an ongoing struggle for equality that continues today.

In 2021, Tad Munemitsu’s daughter Janice published The Kindness of Color: The Story of Two Families and Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, the 1947 Desegregation of California Public Schools. The Kindness of Color is a book-length account of her family’s story and their connection with the Mendez family, the Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, et al. case, and the stories of many kindnesses that the Munemitsu and Mendez families received by others in the midst of racism and adversity. Sylvia Mendez wrote the foreword of The Kindness of Color.

Winifred Conkling’s 2011 novel Sylvia and Aki provides a fictional account of the Mendez and Munemitsu families’ story for third through fifth grade readers.

Densho documents and preserves the history of Japanese American incarceration in the United States. Its website digitally archives oral histories, historical photographs, and other primary sources. The website also features lesson plans, podcast episodes, educational essays, videos, and an encyclopedia that interpret these stories.

For more information about the incarceration of Japanese Americans at the Poston War Relocation Center on the Colorado River Indian Reservation, visit the Poston Preservation website.

The Walk the Farm website explores the history of Japanese American farms in California. Through historical photographs and narrative text, it also features the families who lived and worked on them, including the Munemitsus.

The Library of Congress’s Latinx Resource Guide: Civil Rights Cases and Events in the United States provides a historical overview and additional web and book resources about Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, et al. and public school desegregation in California.

The National Archives compiled this collection of primary sources related to Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, et al. These documents may be especially useful for educators in document analysis activities.

President Obama awarded Sylvia Mendez the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2011. To learn more about what receiving this honor meant to Mendez, check out this video (2 minutes, 27 seconds).

In 2020, Chapman University Chair of Special Collections and Archives Annie Tang, wrote an article for the Japanese American paper, Pacific Citizen, that shines a light on the life and legacy of the Munemitsu family and their connection to Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, et al.

Growing Up Behind Barbed Wire (Fall 2023) is a 7-minute documentary directed by Brendan Bubion that features the stories of Kazuko and Akiko Munemitsu. Utilizing a unique animation style that evokes the hand-made toys and objects made in the camp paired with archival materials and footage from the historic location of the camp, the film explores the dichotomy between the innocence of a child's perspective and the traumatic injustice surrounding them.

To learn more about the impacts of the Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, et al. case, check out the (H)our History Lesson plan, “Bringing together the Brown v. Board of Education Case” from Teaching with Historic Places.

Introduction

By Melissa Hurtado, Heritage Education Fellow, and Jade Ryerson, ACE Fellow and Consulting Historian funded through a cooperative agreement between the National Council on Public History and the National Park Service, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education

Munemitsu, Janice. The Kindness of Color: The Story of Two Families and Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, the 1947 Desegregation of California Public Schools. Foreword by Sylvia Mendez. Self-published, Janice Munemitsu, 2021.

Tang, Annie. “The Munemitsu Legacy: The Japanese American Family Behind Mendez v. Westminster: California’s First Successful Desegregation Case.” The Pacific Citizen. December 18, 2020. https://www.pacificcitizen.org/the-munemitsu-legacy/.

Questions of Land, Labor, and Loyalty: Japanese Incarceration and the Munemitsu Family

By Marjorie Justine Antonio, NCPE Intern and ACE CRDIP Intern, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education

“Finding aid for the Munemitsu-Sasaki family collection.” Frank Mt. Pleasant Library of Special Collections and Archives, Leatherby Libraries, Chapman University. Processed by Rand Boyd, July 2010; reprocessed by Annie Tang, July 2019; expanded historical notes researched and written by intern Kathy Morgan, June 2019. Last updated August 2023. https://chapman.lyrasistechnology.org/repositories/3/resources/113.

Hittenberger, Jeff. “Aki’s Story: On Relocation and Resilience.” The Deeper Learning Podcast, May 8, 2017. Podcast, website, 35:03. https://deeperlearning.ocde.us/ep-02-akis-story-on-relocation-and-resilience/.

Munemitsu, Janice. The Kindness of Color: The Story of Two Families and Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, the 1947 Desegregation of California Public Schools. Foreword by Sylvia Mendez. Self-published, Janice Munemitsu, 2021.

“Tad Munemitsu oral history interview conducted by Katharine H. Snope in Garden Grove, California, 1976-08-16.” From the California State University Fullerton, Japanese American Oral History Project. Transcript. https://cdm16855.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16855coll4/id/57808 (Accessed March 18, 2023.)

Tang, Annie. “The Munemitsu Legacy: The Japanese American Family Behind Mendez v. Westminster: California’s First Successful Desegregation Case.” The Pacific Citizen. December 18, 2020. https://www.pacificcitizen.org/the-munemitsu-legacy/.

Education for All: The Mendez Family's Story of Inclusion and Courage

By Melissa Hurtado, Heritage Education Fellow, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education

City of Westminster. “Mendez Historic Freedom Trail and Monument.” Projects. https://www.westminster-ca.gov/our-city/project-w/projects/mendez-historic-freedom-trail-and-monument.

McCormick, Jenniffer and César J. Ayala. “Felícita ‘La Prieta’ Méndez (1916–1998) and the End of Latino School Segregation in California.” CENTRO Journal 19, no. 2 (Fall 2007): 13-15. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/377/37719202.pdf.

Munemitsu, Janice. The Kindness of Color: The Story of Two Families and Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, the 1947 Desegregation of California Public Schools. Foreword by Sylvia Mendez. Self-published, Janice Munemitsu, 2021.

Reyes, Raul A. “A Latino Family Paved the Way for School Desegregation. It’s Still ‘Unknown’ History.” NBC News. Last updated September 20, 2021, 11:07 AM CDT. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/latino-family-sylvia-mendez-pivotal-desegregation-fight-rcna2068.

Tang, Annie. “The Munemitsu Legacy: The Japanese American Family Behind Mendez v. Westminster: California’s First Successful Desegregation Case.” The Pacific Citizen. December 18, 2020. https://www.pacificcitizen.org/the-munemitsu-legacy/.

The Munemitsu Farm

By Alyssa Eveland, Telling All Americans' Stories Fellow, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education

Munemitsu, Janice. The Kindness of Color: The Story of Two Families and Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, the 1947 Desegregation of California Public Schools. Foreword by Sylvia Mendez. Self-published, Janice Munemitsu, 2021.

———. “Munemitsu Farms.” Walk the Farm. https://www.walkthefarm.org/munemitsu-farms.

Poston War Relocation Center

By Jade Ryerson, ACE Fellow and Consulting Historian, funded through a cooperative agreement between the National Council on Public History and the National Park Service, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education

Burton, Jeffrey F., Mary M. Farell, Florence B. Lord, and Richard W. Lord. “Poston Relocation Center.” Chap. 10 in Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites. Publications in Anthropology 74. Tuscon, AZ: Western Archeological and Conservation Center, National Park Service, 1999; revised July 2000). https://www.nps.gov/parkhistory/online_books/anthropology74/ce10.htm.

Estes, Don. “The Road to Poston: A Brief Historical Summary.” Poston Preservation. https://www.postonpreservation.org/poston-internment.

Fujita-Rony, Thomas. “Poston (Colorado River).” Densho Encyclopedia. Last updated October 16, 2020. https://encyclopedia.densho.org/Poston%20(Colorado%20River).

Niiya, Brian. “Ten Things That Made Poston Concentration Camp Unique.” Densho Encyclopedia. October 8, 2019. https://densho.org/catalyst/ten-things-that-made-poston-unique/.

Varner, Natasha. “Sold, Damaged, Stolen, Gone: Japanese American Property Loss During WWII.” Densho Encyclopedia. April 4, 2017. https://densho.org/catalyst/sold-damaged-stolen-gone-japanese-american-property-loss-wwii/.

Setting the Precedent: Mendez v. Westminster and the US Courthouse and Post Office

Adapted by Melissa Hurtado, Heritage Education Fellow, and Marjorie Justine Antonio, NCPE Intern and ACE CRDIP Intern, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education

Chavez, Herman Luis and María Guadalupe Partida. “1946: Mendez v. Westminster.” A Latinx Resource Guide: Civil Rights Cases and Events in the United States. Library of Congress. Edited by Suzanne Schadl and María (Dani) Thurber. Last updated December 30, 2020. https://guides.loc.gov/latinx-civil-rights/introduction.

National Archives and Records Administration. “Mendez v. Westminster School District: Related Primary Sources.” Educator Resources. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/mendez-case.

Robbie, Sandra, dir. Mendez v. Westminster: For All the Children/Para Todos Los Niños. 2003; Sandra Robbie Productions, 2020. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=F46Mlzt2tFc.

Wollenberg, Charles. “Mendez v. Westminster: Race, Nationality and Segregation in California Schools.” California Historical Quarterly 53, no. 4 (1974): 317–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/25157525.

Education Behind Barbed Wire

By Alyssa Eveland, Telling All Americans' Stories Fellow, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education

Poston Adult and Vocational Training Education Department. The Light of Learning. Poston, AZ: Poston War Relocation Center, 1945. Gerth Archives and Special Collections, California State University, Sacramento. https://cdm16855.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p16855coll4/id/10685.

Munemitsu, Janice. The Kindness of Color: The Story of Two Families and Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, the 1947 Desegregation of California Public Schools. Foreword by Sylvia Mendez. Self-published, Janice Munemitsu, 2021.

National Park Service. “Poston Elementary School, Unit 1, Colorado River Relocation Center.” Place. March 11, 2019. https://www.nps.gov/places/colorado-river-relocation-center.htm.

Oppenheim, Joanne. Dear Miss Breed: True Stories of the Japanese American Incarceration During World War II and a Librarian who Made a Difference. Foreword by Elizabeth Kikuchi Yamada. New York: Scholastic, 2006.

Tunnell, Michael O. Desert Diary: Japanese American Kids Behind Barbed Wire. Charlesbridge Publishing Inc., 2020.

Visualizing Injustice: Mendez v. Westminster | Social Justice Art by Incarcerated Youth

By Marjorie Justine Antonio, NCPE Intern and ACE CRDIP Intern, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education

Dierking, Eleanor. “History on the Walls: The Santa Ana Courthouse Murals.” California Supreme Court Historical Society Newsletter (Fall/Winter 2017): 15-18. https://www.cschs.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/2017-Newsletter-Fall-History-on-Walls.pdf.

Hanigan, Ian. “The Story of Mendez v. Westminster.” The Deeper Learning Podcast, February 27, 2017. Podcast, website, 35:16. https://deeperlearning.ocde.us/ep-01-mendez-v-westminster/.

Mickadeit, Frank. “Jailed Artists Create Works for the New Courthouse.” Orange County Register. Last updated September 13, 2021, 2:16 PM. https://www.ocregister.com/2009/10/14/jailed-artists-create-works-for-the-new-courthouse/.

Shin, Esther. “Celebrating Fiesta Mendez: California’s Gold ‘Manzanar’ Episode Screening and Discussion.” Chapman University Library blog. October 16, 2017. https://blogs.chapman.edu/library/2017/10/16/celebrating-fiesta-mendez/.

Staggs, Brooke. “Festival Marks 70th Anniversary of Orange County Case That Helped Desegregate Schools.” Orange County Register. October 14, 2017. https://www.ocregister.com/2017/10/14/festival-marks-70th-anniversary-of-orange-county-case-that-helped-desegregate-schools/.

Additional People

By Jade Ryerson, ACE Fellow and Consulting Historian funded through a cooperative agreement between the National Council on Public History and the National Park Service, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Eudcation

Carpio, Genevieve. “Unexpected Allies: David C. Marcus and His Impact on the Advancement of Civil Rights in the Mexican-American Legal Landscape of Southern California.” In Beyond Alliances: The Jewish Role in Reshaping the Racial Landscape of Southern California. Edited by Bruce Zuckerman, George J. Sánchez, and Lisa Ansell, 1–32. Purdue University Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt6wq518.5.

Constitutional Rights Foundation. “Mendez v. Westminster: Paving the Way to School Desegregation.” Bill of Rights in Action 23, no. 2 (Summer 2007): https://www.crf-usa.org/bill-of-rights-in-action/bria-23-2-c-mendez-v-westminster-paving-the-way-to-school-desegregation.

Jauregui, Eddie A. and Barbara A. Martinez. “Mendez v. Westminster: The Mexican-American Fight for School Integration and Social Equality Pre-Brown v. Board of Education.” fedbarblog (blog). June 16, 2021. https://www.fedbar.org/blog/mendez-v-westminster-the-mexican-american-fight-for-school-integration-and-social-equality-pre-brown-v-board-of-education/.

Marshall, Thurgood, Robert L. Carter, and Loren Miller. “Brief for the National Association of Colored People as amicus curiae.” Westminster v. Mendez, 161 F2d. 774 (9th Cir. 1947).

Munemitsu, Janice. The Kindness of Color: The Story of Two Families and Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, the 1947 Desegregation of California Public Schools. Foreword by Sylvia Mendez. Self-published, Janice Munemitsu, 2021.

Sadlier, Sarah. "Mendez v. Westminster: The Harbinger of Brown v. Board." Ezra’s Archives 4, no. 1 (Spring 2014): 76-89. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/47956.

Wollenberg, Charles. “Mendez v. Westminster: Race, Nationality and Segregation in California Schools.” California Historical Quarterly 53, no. 4 (1974): 317–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/25157525.

Conclusion

By Marjorie Justine Antonio, NCPE Intern and ACE CRDIP Intern, and Jade Ryerson, ACE Fellow and Consulting Historian funded through a cooperative agreement between the National Council on Public History and the National Park Service, Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education

Munemitsu, Janice. The Kindness of Color: The Story of Two Families and Mendez, et al. v. Westminster, the 1947 Desegregation of California Public Schools. Foreword by Sylvia Mendez. Self-published, Janice Munemitsu, 2021.

Tang, Annie. “The Munemitsu Legacy: The Japanese American Family Behind Mendez v. Westminster: California’s First Successful Desegregation Case.” The Pacific Citizen. December 18, 2020. https://www.pacificcitizen.org/the-munemitsu-legacy/.

Entangled Inequalities: Japanese Incarceration and Mendez, et al. v. Westminster School District of Orange County, et al. is a collaborative project developed in 2022-2023 by interns and fellows with the Cultural Resource Office of Interpretation and Education: Marjorie Justine Antonio, NCPE Intern and ACE CRDIP Intern; Alyssa Eveland, Telling All Americans' Stories Fellow; Melissa Hurtado, Heritage Education Fellow; and Jade Ryerson, ACE Fellow and Consulting Historian with the National Council on Public History.

The three-part companion lesson series Education Inequalities was developed by Alison Russell, Educator and Consulting Historian. It was funded by the National Council on Public History's cooperative agreement with the NPS.

Acknowledgements: Paloma Bolasny, Hermán Luis Chávez, Jessica Dauterive, Sarah Lane, Barbara Little, Eleanor Mahoney, Alison Russell, Megan Springate, and Ella Wagner. With gratitude to Janice Munemitsu and Annie Tang for their kindness and generosity, including their subject matter expertise and editing assistance. Additional thanks to Chapman University's Frank Mt. Pleasant Library of Special Collections and Archives for providing images.

Tags

- entangled inequalities

- world war ii

- wwii

- ww2

- world war ii home front

- japanese american incarceration

- japanese american history

- japanese american confinement

- aapi

- asian american and pacific islander heritage

- asian american and pacific islander history

- latino

- latino history

- latino heritage

- american latino history

- american latino heritage

- mexican american

- mexican american history

- puerto rico

- puerto rican

- civil rights

- legal history

- migration and immigration

- arts culture and education

- education

- school desegregation

- westminster

- orange county

- los angeles

- california

- poston

- arizona

- citizenship

- japanese americans

- japanese american

Last updated: May 31, 2024