Last updated: September 26, 2024

Article

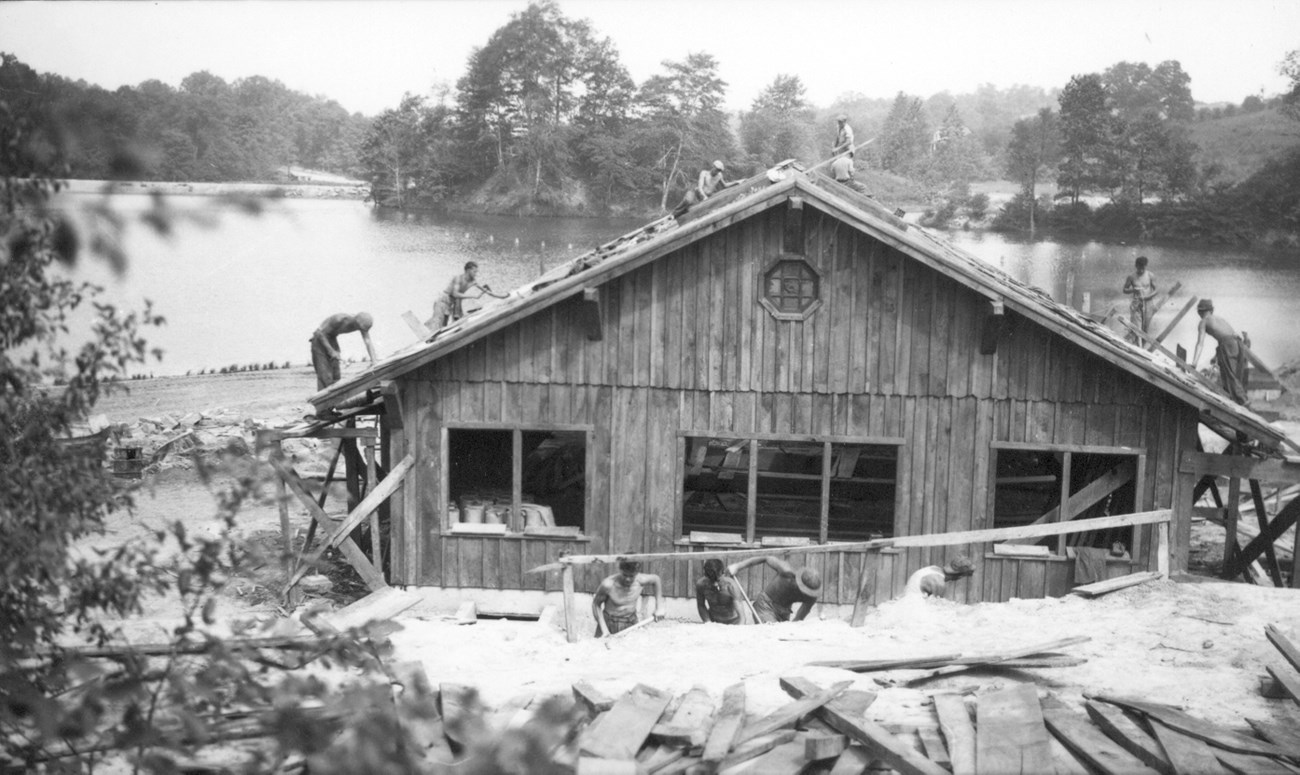

The Legacy of the Civilian Conservation Corps at Cuyahoga Valley

Courtesy Summit Metro Parks

In 1932, the United States found itself deep in the desperate economic crisis of the Great Depression and needed a radical remedy. A new president proposed the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) as a solution that would put people to work while rebuilding America. In the Cuyahoga Valley, the CCC changed both the landscape and its enrollees. CCC “boys” created parks out of farm-worn land, planting trees and adding amenities in what is now the Virginia Kendall unit of Cuyahoga Valley National Park.

Courtesy The Cleveland Press Collection

A Desperate Need

The Crash of 1929 was the greatest stock market crash in history. By 1932, one out of four Americans was unemployed. Many who held jobs had drastically reduced wages. Hungry for relief and hope, the nation overwhelmingly elected a new man of action: President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. His election was based on his far-reaching plan to restart the nation in a record 100 days. On March 9, 1933, President Roosevelt called Congress into an emergency session to authorize his revitalization plan. It included the Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) Act, which created the CCC. Despite opposition, the President signed the act into law on March 31. He promised that by July a quarter of a million men would be employed in a peacetime army to battle the nation’s abused, neglected, and eroded natural resources. With remarkable speed and cooperation, the plans were proposed, authorized, and implemented within 37 days of Roosevelt’s inauguration.

Coming to the Cuyahoga Valley

During the dark days of the Depression, the Akron Metropolitan Park District (AMPD) had a visionary leader at the helm. Established in 1921, the AMPD was relatively new and had few holdings. Realizing the CCC's potential, Park Director Harold Wagner began drawing up plans to use this peacetime army to improve metropolitan park lands. He also petitioned the state to release management of Virginia Kendall State Park to the AMPD. Strapped with its own budget worries, Ohio consented.

Working patiently through complex paperwork, Director Wagner applied and re-applied to get projects approved. Technically, only national and state parks were eligible for CCC camps. Fortunately, decision makers stretched the rules in Ohio. By fall, approval came.

On December 10, 1933, CCC Company 576 arrived in the Cuyahoga Valley (near today’s Happy Days Lodge) amidst a snow storm. Many enrollees came from urban areas within 100 miles of the valley: from Cleveland, Akron, and western Pennsylvania.

One of the CCC's first tasks was to remove hundreds of American chestnut trees, lost to the fungal chestnut blight. The camp set about "flattening" the land, removing the dead and dying vegetation in preparation for re-foresting the area. The enrollees also began to plant trees and shrubs on overworked farm lands. They built lakes with beaches, bath houses, and swimming areas. At Virginia Kendall, local architect Albert Goode designed the Ledges and Octagon shelters, using local sandstone and “wormy” chestnut wood. At any given period, work was not confined to any single project or park. Progress at Virginia Kendall, Furnace Run, and Sand Run depended on the weather, enrollee’s experience, and available equipment.

Courtesy Summit Metro Parks

Camp Life

After the first year of CCC work, Director Wagner wrote to a National Park Service inspector that the creation of a park for Akron’s citizens was his primary goal. But he came to expand on that idea: “I want you to know that originally I probably saw this program in a much more selfish light than I now see it. I was moved by an interest in securing improvement to Sand Run and to Virginia Kendall. Today… I have become much more interested in what is undoubtedly the most important element of the program, namely the future of the enrollees themselves.”

Courtesy Summit Metro Parks

Organizing the recruits into a conservation army was no easy task. The United States Army stepped in to oversee the camps. In return for their labor, enrollees received $5 per month, while their families received $25. Men worked hard with only the simplest of tools. In return they received employment, food, shelter, skills, and hope.

While the Army managed the camps, the National Park Service was responsible for project oversight and planning. Because the agency managed natural resources, it understood Roosevelt’s vision to restore depleted resources.

Eight to 10 foremen supervised the enrollees’ work. These foremen were joined by eight skilled men from local unemployment rolls called LEMs, or Locally Experienced Men. At Virginia Kendall, LEM Luman Cranz and Roland Arnold provided valuable leadership. Both men were well liked and built their reputations on work done for the CCC—reputations that later led to permanent jobs in the community.

Education was not a part of the ECW Act, but was added later. Several foremen taught classes in carpentry, forestry, practical drafting, photography, and first aid. Some enrollees learned to read; others obtained high school degrees or college credit. The classes at Virginia Kendall offered one of the “best and most diversified” programs in the state. In the field and classrooms, enrollees began to learn skills. For some, these skills led to careers. More universally, the CCC experience taught cooperation and instilled pride.

NPS / Ted Toth

An Enduring Legacy

By 1939, much had been accomplished. At Virginia Kendall Park, the Ledges and Octagon shelters were completed. CCC-built Kendall Lake provided year-round use: a toboggan run in the winter and swimming in the summer. Nearby, the former CCC camp had been re-built as Happy Days Lodge, an overnight summer camp for Akron children. (The lodge was named for Roosevelt’s 1932 campaign song, “Happy Days Are Here Again.”) Other metro parks areas also boasted new facilities, such as Furnace Run’s picnic shelter, lake, and bath house. To the north, Cleveland Metroparks added over 15,000 trees, 2.5 miles of bridle trails, and miles of waterline with labor from their CCC camp.

Moreover, men had been given hope. Enrollees had the opportunity for three “hots” and a “flop,” meaning three hot meals a day and a clean, dry place to sleep. Uniforms were included—more clothes than some men had ever owned. Some learned to read and write; others developed a skill that later served them during World War II or in life.

And the land itself changed. Across the valley, forests grew in place of eroded farms. The public could enjoy designed landscapes and views. The new amenities attracted people to the valley seeking relaxation, recreation, and renewal.

In March 1942, the Virginia Kendall camp shut its doors along with camps nationwide as the country shifted its focus to World War II. But in nine years, a great deal of work had been accomplished in Virginia Kendall Park. Today the National Park Service is the caretaker for the legacy these men left here. Out of hard times and crisis came one of the most beloved retreats within Cuyahoga Valley National Park.

Tags

- cuyahoga valley national park

- ohio

- midwest

- ccc

- civilian conservation corps

- franklin d roosevelt

- new deal

- conservation movement

- labor history

- chestnut blight

- cultural resources

- historic preservation

- historic buildings

- historic camp

- architecture

- parkitecture

- national register of historic places

- nr

- historic district

- ohio and erie canalway

- national heritage areas program

- heritage areas

- cultural landscape