Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: César Chávez.

Previous: Places of Cesar Chavez

Article

From the depth of need and despair, people can work together, can organize themselves to solve their own problems and fill their own needs with dignity and strength.

– Casar Chavez

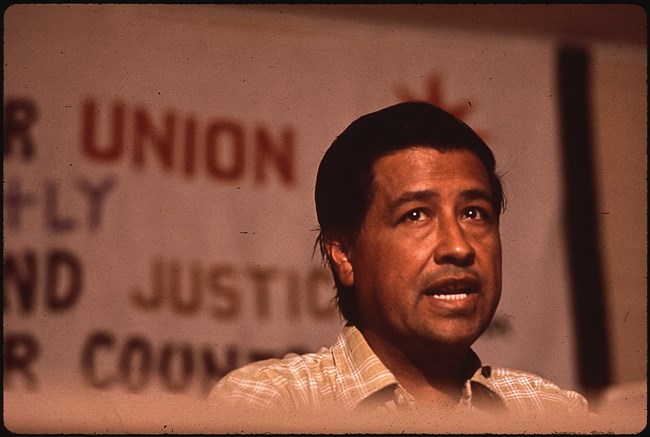

Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons. This photo was provided by the National Archives and Records Administration as part of a cooperation project with Wikimedia Commons.

Cesar Chavez was a fighter for Latino civil rights, especially those of migrant farm workers. Born to Mexican parents in Yuma, Arizona in 1927, Chavez left school in 8th grade and experienced the hardships of farm labor. He worked with other Latino Civil Rights leaders in the Community Service Organization (CSO) before leaving to focus more directly on agriculture. He, along with Dolores Huerta, Larry Itliong, and others, formed the National Farm Workers Association, which would become the United Farm Workers (UFW). Their headquarters is now the César E. Chávez National Monument, a National Park site in California. With the union, Chavez organized the groundbreaking Delano grape strike and the national grape boycott. He also engaged in other non-violent practices, like leading a 340-mile march from Delano to Sacramento, California and performing long fasts to raise awareness for the challenges facing farm workers. Chavez was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom posthumously, recognizing his contributions to equality in America.

How do we build and support community, both locally and with those who provide us with vital resources like food globally?

Cesar Chavez and UFW organized national boycotts, first of grapes then of lettuce to pressure business to improve working conditions.

Think about where your food comes from. Not just the land, but the people who grow, harvest and package your food. Pick three items from your last grocery trip. Look on the labels for the company that makes the product and where the food comes from. This can be done with fruits or vegetables, but also any item you regularly purchase at the grocery store. Then, do a little research and try to answer these questions:

Start on the company’s website. Some will have a tab that says something like “Careers” or “Come work with us.” The salary may be posted there.

If you can’t find the salary, think about why not?

It likely isn’t easy to find an answer to exactly who the workers are who make your food or how they are treated. The United Farm Workers and other unions continue to advocate for better conditions, higher pay and reformed immigration laws for migrant agricultural workers, but also to make these more visible to the general public. How much do you think the way we grow and buy food in the United States has changed since the Delano grape strike and boycott in the late 1960s? How have working conditions for farm workers changed or remained the same?

Chávez believed in a strong community, not just for economic rights, but for civil rights and social health. Wherever he went, he built connections- with other activists like Larry Itiliong and Dolores Huerta, with politicians like Robert F. Kennedy and George McGovern and with everyday volunteers who joined marches, helped build the union headquarters and fed the workers. Who are the members of your community that support you?

Reach out to someone who supports your community and thank them. It doesn’t have to be very formal, but it makes a big difference for people to know that their efforts are recognized and appreciated.

You can take a virtual tour of the César E. Chávez National Monument from the Park Service. As you do, think about the role that space played in organizing for change. How did Chavez and UFW make this a place for community and support for agricultural workers?

The tour will take you inside the Visitor’s Center and museum. Inside, choose three objects that stand out to you. Think about the following questions:

The museum preserved Chavez’s office as it would have been when he was working. What benefits does this offer us as historians? What space in your life best tells a story of your values and your actions?

Alternate tour of the museum can be taken through Google Arts and Culture

Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: César Chávez.

Previous: Places of Cesar Chavez

Last updated: September 15, 2025