Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Abby Kelley Foster .

Previous: Places of Abby Kelley Foster

Article

The content for this article was researched and written by Dr. Katherine Crawford-Lackey.

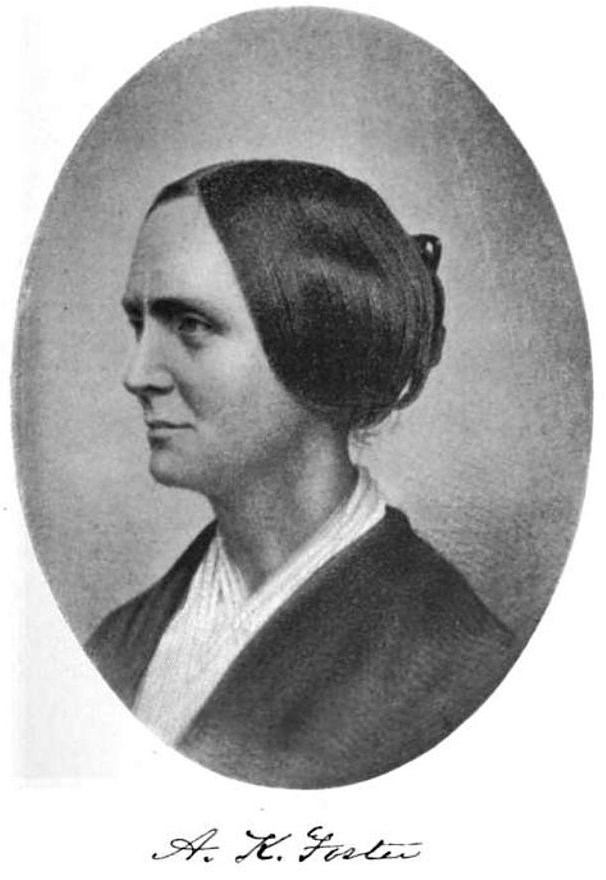

Abby Kelley Foster was an abolitionist (someone opposed to slavery) and an early women’s rights advocate. Devoting her life to creating a more equitable society, she used her skills as a lecturer and educator to advocate for the rights of African Americans and women.

Raised in Worcester, Massachusetts, Abby Kelley Foster was brought up with belief in equality for all people. She shared her beliefs with others and tried to convince them that slavery was wrong. The abolitionist wanted others to recognize that African Americans were equal to white Americans. She also knew that women were just as deserving of rights as men.

In 1838, Abby Kelley Foster she made her first public speech at an anti-slavery convention in Philadelphia. At the time, it was unusual for a woman to speak in public, let alone address a crowd of male onlookers. Her speeches were so effective that she became a highly sought-out lecturer.

She spent most of her life lecturing until she was too sick to travel. Even then she continued to fight for women’s rights. As the co-owner of her house, Liberty Farm, Kelley paid property taxes. But she did not have the legal right to vote on how that tax money was spent. She refused to pay property taxes from 1874 to 1879 as a form of protest.

Explore the early history of the women’s rights movement in the United States.

Learn about some of the challenges women faced in 19th century America and how they overcame discriminatory barriers.

Identify ways in which we can commemorate the perseverance of women’s rights advocates.

In the 1800s, Abby Kelley traveled the lecture circuit to spread her beliefs on abolitionism and women’s rights. How do people today communicate their message and create change? What strategies can you use?

In 1851, Abby Kelley addressed those gathered at the National Woman's Rights Convention in Worcester, Massachusetts. The women’s rights movement had gained much attention since the 1848 meeting in Seneca Fall, New York. At this first meeting, women like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott signed the Declaration of Sentiments. This document was based on the Declaration of Independence and outlined rights of women were entitled to, including suffrage (voting) rights.

At the meeting in 1851, attendees were discussing more than just suffrage rights. They talked about educational advancement, job training, and property rights for women. When Kelley Foster addressed the crowd, she congratulated participants on work well done. She also noted a topic not previously discussed at the convention: the importance of a woman’s labor. Kelley stated:

We complain that woman is inadequately rewarded for her labor. It is true. We complain that on the platform, in the forum, in the pulpit, in the office of teacher, and so on to the end of the list, she does not hold that place which she is qualified to fill; and what is the deep difficulty? I cannot, I will not charge it all upon man. I respond to the statement that it is chargeable upon us as well as upon others.

Kelley acknowledged that systematic discrimination prevented women from achieving their full potential, but she focused on encouraging women to take initiative. She wrapped up her speech by declaring:

Bloody feet, sisters, have worn smooth the path by which you have come up hither.

What do you think she meant by this statement?

Now it’s your turn! Write a speech about a positive change you’d like to see in your community. Consider the following questions:

You can read Kelley’s full speech below or at the Worcester Women’s History Project website. As you do, consider three things Kelley does to persuade her listener.

Mrs. Abby Kelly Foster rose and said:

Madam President: I rise this evening not to make a speech. I came here without any intention of even opening my mouth in this Convention. But I must utter one word of congratulation, that the cause which we have come here to aid, has given such evidence this evening of its success. When genius, that could find ample field elsewhere, comes forward and lays itself on this altar, we have no reason for discouragement; and I am not without faith that the time is not far distant, when our utmost desires shall be gratified, when our highest hopes shall be realized. I feel that the work is more than half accomplished.

I have an idea, thrown into the form of a short resolution, which I wish to present to this Convention, because no one else has brought it forward. I feel that behind, that underneath, that deeper down than we have yet gone, lies the great cause of the difficulties which we aim to remove. We complain that woman is inadequately rewarded for her labor. It is true. We complain that on the platform, in the forum, in the pulpit, in the office of teacher, and so on to the end of the list, she does not hold that place which she is qualified to fill; and what is the deep difficulty? I cannot, I will not charge it all upon man. I respond to the statement that it is chargeable upon us as well as upon others. It is an old, homely maxim, but yet there is great force in it, "Where there's a will, there's a way;" and the reason why woman is not found in the highest position which she is qualified to fill, is because she has not more than half the will. I therefore wish to present the resolution that I hold in my hand:

Resolved, That in regard to most points, Woman lacks her rights because she does not feel the full weight of her responsibilities; that when she shall feel her responsibilities sufficiently to induce her to go forward and discharge them, she will inevitably obtain her rights; when she shall feel herself equally bound with her father, husband, brother and son to provide for the physical necessities and elegances of life, when she shall feel as deep responsibility as they for the intellectual culture and the moral and religious elevation of the race, she will of necessity seek out and enter those paths of Physical, Intellectual, Moral and Religious labor which are necessary to the accomplishment of her object. Let her feel the full stimulus of motive, and she will soon achieve the means.

I believe that the idea embodied in this resolution, though not expressed so clearly as I fain would have had it, points to the great difficulty that lies in our way; and therefore, I feel that it is necessary for us to inculcate, on the rising generation especially, (for it is to these that we must chiefly look,) it is necessary for us to inculcate on them particularly this feeling of responsibility. Let mothers take care to impress upon their daughters, that they are not to enter upon the marriage relation until they are qualified to provide for the physical necessities of a family. Let our daughters feel that they must never attempt to enter upon the marriage relation until they shall be qualified to provide for the wants of a household, and then we shall see much, if not all, that difficulty which has been complained of here, removed. Women revolt at the idea of marrying for the sake of a home, for the sake of a support -- of marrying the purse instead of the man. There is no woman here, who, if the question were put to her, would not say, Love is sufficient. She says it is sufficient, and she believes it; yet behind this lies something else, in more than one case in ten.

Let us therefore inculcate upon our daughters, that they should be able to provide for the wants of a family, and that they are unfit for that relation until they are qualified to do so. If we teach our daughters that they are as much bound to become independent as their brothers, and that they should not hang upon the skirts of a paternal home for support, but secure subsistence for themselves, will they not look out avenues to new employments? Why, we all feel it, we all know it; if women could be taught that the responsibilities devolved equally upon themselves and the other sex, they would seek out the means to fulfill those responsibilities. That is the duty we owe our daughters to-day; that is the duty each one owes to herself to-day, to see to it that we feel that we must enter into business, such as will bring in to the support of our families as much as the labor of our fathers, husbands, and brothers does. Woman's labor is as intrinsically valuable as any other, and why is it not remunerated as well? Because, as has been shown here, because there is too much female labor in the market, compared with the work it is allowed to undertake. There are other means of support; there are other modes of acquiring wealth: let woman seek them out, and use them for her own interest, and this evil will in great part be done away.

Then, again, let every woman feel that she is equally responsible with man for the immorality, for the crime that stalks abroad in our land, and will she not be up and doing, in order to put away that vice? Let every woman understand that it is for her to see that disease be not inflicted on the community, and will she not seek out means to do it away? If she feel that she is as competent to banish superstition, and prejudice, and bigotry, from the world as her brother, will she not be up and doing? Here is the great barrier to woman's obtaining her rights. Mary Wolstonecraft was the first woman who wrote a book on "Woman's Rights;" but a few years later, she wrote another, entitled "Woman's Duty;" and when woman shall feel her duty, she will get her rights. We, who are young on this question of Woman's Rights, should entitle our next book "Woman's Duties." Impress on your daughters their duties; impress on your wives, your sisters, on your brothers, on your husbands, on the race, their duties, and we shall all have our rights.

Man is wronged, not in London, New York, or Boston alone. Look around you here in Worcester, and see him sitting amidst the dust of his counting room, or behind the counter, his whole soul engaged in dollars and cents, until the Multiplication Table becomes his creed, his Pater noster, and his Decalogue. Society says, keep your daughters, like dolls, in the parlor; they must not do anything to aid in supporting the family. But a certain appearance in society must be maintained. You must keep up the style of the household. You are in fault if your wife do not uphold the condition to which she was bred in her father's house. I put this before men. If we could look under and within the broadcloth and the velvet, we should find as many breaking hearts, and as many sighs and groans, and as much of mental anguish, as we find in the parlor, as we find in the nursery of any house in Worcester. But woman is vain and frivolous, and man is ignorant; and therefore, he is what he is. Had his daughters, had his wife, been educated to feel their responsibilities, they would have taken their rights, and he would have been a happy and contented man, and would not have been reduced to the mere machine for calculating and getting money he now is.

My friends, I feel that in throwing out this idea, I have done what was left for me to do. But I did not rise to make a speech -- my life has been my speech. For fourteen years I have advocated this cause by my daily life. Bloody feet, sisters, have worn smooth the path by which you have come up hither. (Great sensation.) You will not need to speak when you speak by your everyday life. Oh, how truly does Webster say, Action, action, is eloquence! Let us, then, when we go home, go not to complain, but to work. Do not go home to complain of the men, but go and make greater exertions than ever to discharge your every-day duties. Oh! it is easy to be lazy; it is comfortable indeed to be indolent; but it is hard, and a martyrdom, to take responsibilities. There are thousands of women in these United States working for a starving pittance, who know and feel that they are fitted for something better, and who tell me, when I talk to them, and urge them to open shops, and do business for themselves, "I do not want the responsibility of business -- it is too much." Well, then, starve in your laziness!

Oh, Madam President, I feel that we have thrown too much blame on the other side. At any rate, we all deserve enough. We have been groping about in the dark. We are trying to feel our way, and oh! God give us light! But I am convinced that as we go forward and enter the path, it will grow brighter and brighter unto the perfect day.

I will speak no longer. I speak throughout the year, and those of you who speak but once should take the platform. I hope, however, that you do not feel that I speak to you in anger. Oh, no; it is in the hope of inducing you to be willing to assume responsibilities, to be willing to have a sleepless night occasionally, and days of toil and trouble; for he that labors shall have his reward; he that sows shall reap. My teacher in childhood taught me a lesson, which I hope I never shall forget. She had appointed me a task, and when she asked me if I had learned it, I said, "No, it is too hard." "Well," said she, "go into the road and pick me up an apron full of pebbles." I did it. "It was easy to do it," said she. "Oh, yes," I replied. "Go out again," said she, "and pour them down, and bring me in an apron full of gold." It was impossible. "Yes," said my teacher, "you can get that only by earnest labor, by sacrifice, by weariness." I learned my lesson, I accomplished my task; and I would to God that every person had had similar instruction, and learned the necessity of toil -- earnest, self-sacrificing toil. (Loud cheers.)

Abby Kelley Foster was not the only woman abolitionist. In fact, many women were involved in the cause. Black and white women lectured, published newspaper articles, and even risked their lives and freedom to assist those escaping slavery. Some women abolitionists include Maria W. Stewart, Ellen Craft, Eliza Gardner, Clara Vaught, Nancy Prince, and Harriet Tubman.

Choose one of the women listed above (or another woman abolitionist you find interesting) and research their life. Consider the following questions as you do:

When was this woman born?

How did she become involved in abolitionists?

Who did she work with?

What risks did she take to help others?

What is she most known for today?

While she was not present at the 1848 Seneca Falls ConvenElizabeth Cady Stanton with her talk of women’s rights. When Stanton, Lucretia Mott, and other activists met in 1848, they drafted a Declaration of Sentiments. It listed the rights women believed they were entitled to, including suffrage (or voting) rights.

The first part of this document reads:

When, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one portion of the family of man to assume among the people of the earth a position different from that which they have hitherto occupied, but one to which the laws of nature and of nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes that impel them to such a course.

We hold these truths to be self-evident; that all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. The history of mankind is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations on the part of man toward woman, having in direct object the establishment of an absolute tyranny over her. To prove this, let facts be submitted to a candid world.

The attendees then listed the rights they had been denied. A few of their frustrations included:

He has never permitted her to exercise her inalienable right to the elective franchise.

He has compelled her to submit to laws, in the formation of which she had no voice.

He has made her, if married, in the eye of the law, civilly dead.

He has taken from her all right in property, even to the wages she earns.

For two days (July 19-20, 1848), the convention participants discussed the rights women had and the rights they still had to achieve. They edited and developed a final version of the Declaration of Sentiments. 68 women and 32 men signed their names to the document. The members then debated twelve resolutions that called for equality for women in different areas of American society and culture, including the right to vote in public elections. Even among these delegates, a resolution calling for a woman’s right to vote barely passed.

Why do you think the attendees bolded the word “he” at the beginning of each grievance?

Only one-third of the 300 people at the convention signed the Declaration of Sentiments. Why do you think the other 200 refused?

Identify three to five rights that are most important to you. Why are they important to you? What would it be like to live without these rights?

Bibliography:

Sterling, Dorothy. Ahead of Her Time: Abby Kelley and the Politics of Antislavery. New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1991.

Wellman, Judith. “How Abby Kelley Turned Seneca Falls on Its Ear Five Years Before the Seneca Falls Woman's Rights Convention” Worcester Women’s History Project, (May 29, 2004), http://www.wwhp.org/Resources/akfoster.html

http://www.haineshouse.org/haines-house.html

“Abby Kelley Foster’s Speech,” Worcester Women’s History Project, http://www.wwhp.org/Resources/WomansRights/akfoster_1851.html

Part of a series of articles titled Curiosity Kit: Abby Kelley Foster .

Previous: Places of Abby Kelley Foster

Last updated: July 30, 2021