Part of a series of articles titled Administrative History of the National Park Service Inventory & Monitoring Division.

Article

I&M Administrative History: Babbitt Flips the Table

Not long after NPS-75 was published, the Office of Inspector General released the audit that had sent its men to Gary Williams’s new office door earlier in 1992. The report was an indictment of the park service’s habitual underfunding of resource management and science. “Because the Park Service gave greater priority and emphasis to visitor-related issues,” the OIG wrote, it “consequently was not able to provide adequate oversight and funding to protect and conserve natural resources.”1 As a result, resource damage had occurred at multiple parks. The NPS was failing to meet its obligations under the Organic Act.

Some harm came from threats the NPS had known about but failed to mitigate. Using an NPS database, the OIG had identified a $477 million backlog of 4,700 uncompleted projects intended to prevent or mitigate known threats to park resources—yet noted that in 1992, the NPS had allocated only $93 million (10% of the agency’s total budget) to the entire natural resource management program.2 Over the previous nine years, resource management had received about 8% of the total budget. The other 92%, according to the OIG, had been “devoted primarily to visitor-oriented programs.”3

Damage from unknown threats often occurred because the bureau hadn’t implemented sufficient inventory and monitoring activities to detect them. For instance, lack of I&M had hampered the bureau’s response to resource disasters, with devastating consequences. After the Exxon Valdez tanker spilled 11 million gallons of crude oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound, officials at Kenai Fjords National Park, Katmai National Park and Preserve, and Aniakchak National Monument and Preserve were unable to accurately assess the extent of the damage because of a lack of baseline data. After receiving word of the incoming disaster, park staff scrambled to perform preassessments of coastal resources before the oil washed ashore—but their value was limited and not ultimately used to determine losses or damage. Lack of pre-existing data also made it difficult to judge the spill’s long-term effects. At the opposite end of the National Park System, ammonia toxins from a nearby landfill leaked into Florida’s Biscayne Bay for five years, undetected, because park officials had not used a panel that included them during water-quality testing. After park officials were finally notified of the leak, un-ionized ammonia in Biscayne National Park waters was recorded at 32 ppm—1,000 times EPA-recommended levels.4

At Crater Lake National Park, a 1989 survey of Sun Creek found 130 native bull trout—a 96% decrease from the number (3,000) recorded during the last survey, done 42 years earlier. Long-term monitoring during the intervening decades would have alerted park officials to the decline, allowing them to take action before the near-extirpation of the species from the park. Yet in just the second year of funding the I&M program, the NPS was already following a reliable pattern of apportioning funds for science and then diverting them elsewhere. After an initial allocation of $1.9 million in fiscal year 1992, I&M was programmed to receive $4.4 million for fiscal year 1993—but then that number was slashed to a flat $1.9 million, scuttling the program’s 10-year goal of completing the inventories and phasing in prototype parks for monitoring.5

In their response to the OIG’s draft findings, NPS leaders had blamed Congress, complaining that the NPS as a whole had been consistently underfunded, making it impossible to put enough dollars into resource management. In the audit’s final version, the OIG clapped back, pointing out that NPS leaders—not Congress—decided how to distribute whatever funds were allocated. Over and over, those leaders had chosen to dedicate 10% (or less) of the budget to the “conservation” half of the agency’s dual mandate, preferring to spend the vast majority on “use.” The ironic but predictable long-term effect of overinvesting in use was that the very resources people came to see had deteriorated, causing “a reduction in the natural value and attraction of the parks to future generations.”6 In its recommendations, the OIG urged the NPS to fund I&M in a way that would allow the program to complete its initial 10-year project on schedule, but stopped short of suggesting ways the NPS could break its longtime habits and safeguard resource funding in the future.7

Later that year, though, the National Research Council offered some ideas. In “Science and the National Parks,” an NRC subcommittee summarized the recommendations from all external reviews of NPS science dating back to the Leopold Report (including a table showing that inventory and monitoring had been recommended in every major internal and external science review since the 1963 Robbins Report), then added its own review and recommendations. In their view, the NPS needed three things: (1) an explicit legislative mandate to do science, (2) autonomous lines of funding and supervision for science, and (3) a chief scientist who could raise the credibility of science within the organization and strengthen its ties outside it. The subcommittee, which included two members of the Evison group, presented inventory and monitoring as the “absolute minimum” the NPS science program should do, because it would provide a basis for analyzing most other management-relevant questions that might arise.8

In the world envisioned by the National Research Council, researchers and resource managers would be partners, with researchers—whose work was mandated by law—routinely providing input to resource management plans. Free of fiscal and supervisory encumbrance to each other, they would regularly sit down and devise a mutually agreed-upon, scientifically rigorous research plan that would meet short- and long-term management needs. The resulting research would be adequately funded. Results would be objectively analyzed, delivered in a timely manner, and actively incorporated into a logical decisionmaking process. Yet researchers and managers would also understand each other’s constraints. Scientists would “recognize that managers often are compelled to make decisions without the benefit of adequate analysis and will therefore need advice based on the best current scientific information or on the preliminary results of continuing studies.” Managers would recognize that “current research findings can be limited by the lack of baseline data and that this lack of information itself hampers the quick derivation of clear and short-term results.”9

To achieve that level of mutual understanding required routine communication and trust-building over time. In fact, this model, in which scientists worked closely with but were not directly responsible to park superintendents, had been working effectively for years in the NPS Western Region—where, for instance, Gary Davis was assigned to Channel Islands National Park but reported to the region’s chief scientist. But when the NPS’s central science office was split into regional offices in the 1970s, each region had been left to develop its own way of doing things. The Western Region may have set the standard, but the other regions weren’t required to adhere to it, and so different regions followed different models. In her unpublished administrative history of Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit system, Diane Krahe notes that in 1993, an NPS committee proposed that the Western Region model be adopted across the bureau. NPS director James Ridenour was amenable to the idea, but was replaced before it could be implemented.10

Around the same time, new Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt proposed an alternative approach to the scientist/manager relationship: Remove scientists from the NPS entirely. By creating the new “National Biological Survey” (NBS), Babbitt intended to erase any question that DOI researchers were unduly influenced by land managers, by putting them all under the same independent organizational umbrella. Many scientists would be assigned to carry on the same work, from the same work stations—but under the aegis of a separate agency. Extracting biologists from their individual agency silos was also supposed to encourage an ecosystem-management approach to federal lands, reduce duplicative effort, and shore up the government’s ability to identify places where habitat conservation might help prevent the necessity of endangered-species listings.11

When Congress declined to pass authorizing legislation for the NBS in the summer of 1993, Babbitt established it himself, by secretarial order.12 Absent any Congressional funding, the new bureau was staffed with researchers and support personnel reassigned from other bureaus—more than 1,800 in all. Most (~1,300) came from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. The NPS surrendered roughly 170 full-time positions and $20 million in base funding.13 Babbitt appointed two highly respected academic professors to lead the NBS. As director, he chose avian ecologist Ronald Pulliam, director of the University of Georgia’s Institute of Ecology. Small-mammal ecologist James Reichman, previously of Northern Arizona University, Kansas State University, and the National Science Foundation, was tapped to be assistant director for research. Pulliam and Reichman would need someone with bureaucratic experience to help them navigate the federal labyrinth, so Babbitt arranged for Gene Hester to leave his position with the NPS and become deputy director of the NBS.14

The National Biological Survey ran aground almost immediately—doomed by semantics, political paranoia, and Babbitt’s failure to account for the importance of human ties in scientific endeavors. One year after its formation, Republicans were elected to majorities in both houses of Congress, buoyed by the conservative “Contract with America.”15 The contract promised to reduce the presence of government in people’s lives, and rumors began to circulate that in direct contrast to that principle, the goal of the NBS was to root out every possible threatened and endangered species in the country via surveys conducted on private lands—likely resulting in thwarted development opportunities and loss of property value. Soon, there was talk of completely eliminating the new bureau—which now contained a substantial portion of all the scientists in the Interior Department. Babbitt had put most of his eggs in one basket.

A name change ensued. In 1995, Babbitt swapped out “Survey” for “Service” (to tamp down the imagined specter of bureaucrats with clipboards tramping across people’s fields looking for rare rodents so they could seize the property), and issued an order prohibiting employees from working on private lands without permission. But by the following year, amid Congressional plans to zero-out the bureau’s budget, Babbitt shuffled his department again. In October 1996, the National Biological Service was reborn as the Biological Resources Division (later Biological Resources Discipline, currently Ecosystems Mission Area) of the U.S. Geological Survey.

The turmoil behind the scenes was no less dramatic. Swift institutional change was not something US government employees were accustomed to—and in creating the NBS, Babbitt had pulled 1,800 people out of seven DOI agencies where many of them had built their careers, severing the relationships they had established within those agencies and, in many cases, eliminating the logistical support they relied on to do their work. At Channel Islands, for instance, Gary Davis (whose position had been moved to the NBS) found himself unable to continue long-term research on coral reefs and kelp forests because they required SCUBA diving—and the NBS didn’t have a dive program. So instead of collecting data, Davis put his energies into trying to formalize organizational infrastructure that was well-established at the bureau he’d just been forced to leave, in order to continue the same work.16

The effects were also felt in parks. The departed scientists took decades of institutional knowledge about parks and park ecosystems with them, leaving knowledge gaps park managers found difficult to grapple with. Though a handful of superintendents weren’t entirely displeased with the promise of having access to science without having to deal with scientists, it didn’t take long for others, such as Yellowstone’s Mike Finley, to start expressing frustration—sometimes publicly.17 Babbitt got wind of the grumbling, and asked new NPS Associate Director for Natural Resources Mike Soukup what the problem was. Soukup told him what he knew: that taking scientists out of the parks had undermined, rather than strengthened, the use and stature of science in the NPS.18

With no mandate to use science in decisionmaking, and now no scientists anywhere near the room where it happened, superintendents inclined to ignore science were now even more free to do so. Those who valued it no longer had the benefit of day-to-day contact with the people who knew most about it, and found it more difficult than ever to get the scientific attention and information they needed for effective management. In short, the NBS had “removed NPS research from the direct influence of park management, but also made the research less relevant to management needs.”19

A 1996 survey of NPS and NBS staff showed negative effects on both sides of the new bureaucratic divide. Asked about their access to scientific information before and after the creation of the NBS, 49% of NPS respondents said they had “regularly” received scientific assistance prior to the formation of the NBS. Only 19% said they had received scientific assistance “regularly” afterward. Nearly three times as many respondents (32%) said they “never” received scientific assistance after the NPS scientists were transferred, as opposed to before (11%). One-fifth of scientists transferred from the NPS to the NBS reported being either “not encouraged or actively discouraged” from assisting NPS managers after the transfer. More than 50% felt their support from parks had declined.20

On paper, the NBS may have looked like a logical solution to some longtime problems with government science. But what the plan ignored was that for government science to be worth doing, agency leaders had to be convinced of its relevance and utility—a process that requires interpersonal communication and trust. Relationships are built far more easily around a water cooler than over a long-distance telephone consultation—let alone via annual reports or journal articles. The physical absence of scientists in parks left a gap quickly filled with divisional priorities, political pressures, and local influence. More importantly, it ensured science would never be embraced as an integral, routine part of NPS culture and practice. When Secretary Babbitt asked his new associate director what he could do to improve the mood of the superintendents and the morale of NBS researchers, Soukup had a ready answer: send the scientists doing park-based research (~70–80 of the NPS positions originally moved to the NBS) back to the parks.21

Soukup had experienced the problems wrought by the NBS first-hand. He had come to Washington through a revolving door that took him, in short order, from director of the NPS South Florida Research Center to an NBS unit in Gainesville and then back to the NPS. Just prior to his NBS transfer, Soukup had announced the reorganization of the SFRC. Since its inception 20 years earlier, the center had never received a substantial funding increase. As a result, inflation and rising costs had eroded the budget to the point where it had had to stop research at all the parks it served except Everglades. Even then, the SFRC was relying on $2 million in competitive project funds—referred to in NPS parlance as “soft money” with no expectation of long-term renewal—to support its efforts. And as its funding had decreased, its responsibilities had increased to include resource management as well as research.22

Recognizing the current model was unsustainable, the leaders of the center re-envisioned it. To this point, its operations had remained organized by subject, with different stovepipes for hydrology, wildlife, vegetation, marine science, and data management. The new model reorganized the center by function, with different sections for inventory and monitoring, data management, research, and resource management. In addition to building efficiencies, the integrated subject approach was also better situated to take an ecosystem view, and so better in line with the emerging ecosystem management approach that was gaining traction in the NPS during this period. But the research component was defined just in time for the NBS to come along and pluck it out. Soukup and his colleagues were sent to the NBS’s South Florida/Caribbean field unit at the University of Florida, where they experienced the same kind of logistical-support problems that had frustrated Gary Davis in California.

As associate director, Soukup was determined to restore park managers’ access to management-relevant science—and scientists. But ultimately, Babbitt decided to move the NBS into the USGS intact. In parks that could afford it, superintendents favorable to science slowly started re-creating and re-hiring some of the positions they’d surrendered. In other places, the loss felt more permanent.

The nascent I&M program had been shaken and splintered by the creation of the NBS, but was still extant. Initially, the entire program was slated for transfer out of the NPS; Babbitt’s order creating the NBS seemed specifically intended to sweep I&M into it. The mission of the new bureau was “to gather, analyze, and disseminate the biological information necessary for the sound stewardship of our Nation’s natural resources.” To accomplish that mission, the NBS was assigned to perform biological research in support of management; “inventory, monitor, and report on the status and trends in the Nation’s biotic resources;” and transfer the information gained to resource managers.23

But not all of the NPS I&M program’s work was biological. Of the 12 basic inventories, only a handful focused on biotic resources. This meant I&M’s resources of interest now fell into two bureaucratic categories: biological, falling under NBS purview, and non-biological, which remained the responsibility of the NPS. Biological inventories, such as vegetation mapping, were now an NBS responsibility. They, and their associated funding, were transferred to the new agency. For the next several years, when the I&M program needed to initiate a vegetation mapping project, Gary Williams had to request the funding, and work, from the NBS. Non-biological inventories, such as soils, geology, and water, remained with the NPS—along with Gary Williams, who, as I&M program coordinator, was not classified as a research scientist.24

Soon, the program was also split according to function. At a Washington meeting whose purpose was to identify which NPS staff should be transferred to NBS, Gary Davis successfully argued that once the design and protocol-development phases of a prototype monitoring program were complete, and turned over to park staff for implementation, the program’s function was no longer “research.” At that point, monitoring became part of routine park operations (like putting the flag up and taking it down), putting it outside the mission of the NBS. Having reached that stage, Channel Islands and Shenandoah national parks got to keep their monitoring programs. For the other two prototype parks (Denali and Great Smoky Mountains), a deal was struck with lasting ramifications. With protocol development designated a “research function,” the design of prototype monitoring programs would be done with funding and full-time employees from the NBS (later USGS-BRD).25 When monitoring was ready to be implemented, it was considered to be operational, and responsibility for program funding and staffing was transferred to the National Park Service.26

Re-defining monitoring as a management, rather than research activity, allowed the NPS to hold on to some small aspect of its biological science program. In fact, the park service had always been ambivalent about what kinds of activities constituted “research.” The authors of a 1945 report on research in the NPS opined, “Results of routine observations or taxonomic studies are not classified as the results of research in the strict sense of the word.” “True research” involved “bringing to light new data, information of a new or revised interpretation.”27 In the 1980s, the Western Region research scientists had initially rebuffed Gary Davis’s I&M plans as not “real research.” In response to Congressional questions about how much money the NPS spent on research, an NPS spokesperson explained in 1987 that for budget purposes, “‘Research’” could be defined either as “all data collection and analysis, not only original investigations . . . [including] monitoring activities for air quality, water quality, etcetera, and other long-term monitoring and basic inventories of park resources”—or “as only original investigations.”28

But after the advent of the NBS, park service staff had to be careful about the language they used to describe the work done by employees whose duties involved biological science. In the past, “inventory and monitoring” and “research” had often been discussed as two different components of a single necessary science program. Now, lines had been drawn between what were appropriately NPS functions (biological monitoring) and NBS functions (biological research), and each bureau had to stick to its own business. From the start, NBS critics in Congress had worried about functional duplication, correctly predicting that the agencies whose scientists had been harvested would eventually strive to replace them.29 For their part, NBS staffers, who had been through a considerable amount of upheaval, were concerned about their own relevancy if their former bureaus sought to revive their own biological research efforts—concern that sometimes lent itself to territoriality.30 Fraught as the whole experience had been, Babbitt himself tended to be sensitive, throughout his tenure, to what he suspected were efforts to undermine the NBS/BRD.31

There were also legal questions to consider. After facing repeated questions about whether he’d had the authority to create the NBS in the first place, Babbitt requested an opinion from a departmental lawyer. In May 1994, solicitor John Leshy confirmed that Babbitt had been within his rights as secretary to reorganize the department—and in the process, to revoke functions from some bureaus and redelegate them to others.32 In the sense that the NBS had not been so much created as assembled, Frankenstein-style, out of parts from other bureaus, Babbitt was on solid legal ground. But if the cannibalized bureaus resumed the functions that had been reassigned to the NBS, then the ground could get shaky. The end result of all this has been a lasting reluctance to describe the work of NPS I&M as “research.”

Within I&M, the split in functions complicated the budget. Biological inventories were funded by the NBS, with monies that were previously part of the I&M budget. On the monitoring side, the funding was shifted back and forth depending on the prototype’s development phase. A table of sources for Denali’s prototype funding shows one example of how support originated with the NPS, then moved to the NBS and, after the monitoring design and protocols were complete, back again.33

Table 3. Funding history of the Denali National Park Long-Term Ecological Monitoring program, 1992–2002.A| Agency | Funding source | Design | Development | Implementation/Transition | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 1993 | 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | ||

| NPS | I&M | 140B | 275B | – | 60C | 35D |

35D

165B |

20

266.5B |

266.5B | 485B | 485B | 485B |

| NPS | DENA-Base | – | – | – | – | – | – | 345.5B | 345.5B | 506B | 493B | 493B |

| NPS | DENA-Other | – | – | – | – | – | – | 33.5 | 33.5 | 33.5 | 33.5 | 33.5 |

| NBS | NBS | 275B,E | 275B | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||

| USGS | BRD | – | – | – | 275B | 150 | 205 | 205 | 285 | – | – | |

| USGS | ASC-Base | – | – | – | – | – | – | 136 | 136 | 136 | 163 | 113 |

| Total | 140 | 275 | 275 | 335 | 310 | 350 | 1006.5 | 986.5 | 1445.5 | 1174.5 | 1124.5 | |

AAcronyms: NPS=National Park Service I&M=inventory & monitoring DENA=Denali NBS=National Biological Survey/Service USGS=US Geological Survey BRD=Biological Resources Division ASC=Alaska Science Center.

BMajority funding source.

C$60K funding transfer from I&M program to park base for GIS Coordinator.

D$35K funding transfer from I&M program to park to fund program coordinator position.

E$275K transfer from the park to the National Biological Service, now the Alaska Science Center.

The introduction of the NBS to the I&M program also muddied staff supervision in I&M. For instance, after Alaska’s I&M coordinator, Lyman Thorsteinson, was transferred to the NBS, the servicewide coordinator and the prototype coordinator worked for two different bureaus, while much of the on-the-ground work was carried out by park staff.34 By February 1994, ideological divisions had opened over the direction of the program. NPS staff from the park and Alaska Regional Office were unable to agree with NBS staff about the best use of available funds or the appropriate scale for monitoring (site-specific vs. watershed).35 A 1995 program summary detailed a laundry list of ongoing problems, including “limited funding, uneven funding for different studies, data backlogs, lack of space to accommodate needed workers, inefficiencies of working with two agencies, and the lack of ability for management to make use of the data collected.”36

Adding to the general aura of instability, the NPS underwent its own internal restructuring in 1994, driven in part by a push for decentralization. The number of regional offices was reduced, the number of area support offices increased, and when possible, program management was moved out of Washington.37 Gary Williams got his chance to move the I&M program to Colorado. He chose Fort Collins over Lakewood, and I&M has been headquartered there ever since.38 With much of the NPS’s Wildlife and Vegetation Division transferred to NBS, Williams found himself in Fort Collins with an assortment of other resource program specialists. Some were placed in the new NPS Biological Resources Management Division (BRMD) and, just as there had been discussion about moving I&M into the NBS, there was discussion about moving I&M into BRMD. Ultimately, I&M remained apart from BRMD for the same reason it had remained apart from the NBS: much of its work was non-biological. Instead, it became part of the new Natural Resource Information Division, cobbled together from what Williams described as “bits and pieces” of programs that had been similarly dissembled by the NBS or the NPS restructuring, including resource planning, publications, interpretation, and GIS. The new division was led by Rich Gregory, the former head of a US Fish and Wildlife Service publications group that was being dissolved.39

Despite this avalanche of organizational, fiscal, and physical realignments, the work went on. In the five years between the start of planning in 1993 and 1998, the I&M program funded 560 natural resource inventories. The priority order of inventories and parks was developed by regional NPS staff in response to ranking information received from park staff in 1992. Although the HTF plan had called for inventories to be conducted park by park, with priority going to parks whose inventories were already closest to completion, followed by parks whose inventories were in the worst shape, the I&M Advisory Committee took a slightly different approach. Taking the park priorities into account, regional staff compiled a regionwide list of resource inventory priorities and then ranked them by park across all 12 themes. Staff from the Washington office merged the information across regions to develop a servicewide listing of priorities for each inventory. Then, in July 1993, an IMAC subcommittee developed a park-by-park priority sequence for each inventory. A 1993 memo from Associate Director Denny Fenn explained the process and included the full, ordered lists of inventories and parks.40 For most inventories, the IMAC sequence followed some version of the servicewide listing, with some inventory-specific modifications (parks designated as Class I under the Clean Air Act, for instance, went to the head of the line for air-quality inventories).

Before starting any inventories, parks needed to understand the scope of what research had already been done, so the Natural Resource Bibliographies were done first, across the board. Intended to solve some of the longstanding recordkeeping problems revealed in the fallout from William Newmark’s work in the 1980s, the bibliographies incorporated all of a park’s historical scientific material, including unpublished reports, journal articles, maps, photograph collections, and other sources of natural resource information, into an automated database. They were prioritized region by region, according to overall need. The Alaska parks were first, followed by parks in the Southwest, Rocky Mountain, Mid-Atlantic, National Capital, Southeast, Midwest, Western, and North Atlantic regions. Parks in the Pacific Northwest Region, many of which already had bibliographies, were near the bottom of the list; their funding would be used for updates and digital conversion. To maintain the databases and provide user support, the program funded an “NRBIB coordinator” position.

By 1998, most of the in-park work for the natural resource bibliographies had been completed. Maps of vegetation communities and soil types would require base cartography, which was easily acquired from the U.S. Geological Survey, so that was another inventory completed early in the process.41 Complete or partial base cartographic data were acquired for 240 parks by 1998. Soils surveys were underway in 41 parks. Inventories of geology, air quality, meteorology, and species lists were still in the planning and groundwork stages. About one-quarter of the 560 funded inventories were of water quality data and analysis. Sometimes called the “Horizon Reports,” the water quality inventories were produced through a private–public collaboration between private contractor Horizon Systems, Inc., the I&M program, the NPS Water Resources Division, and multiple state and federal agencies. They were intended to provide park staff with a complete accounting of all water-quality stations and data collected in and near the parks and stored in the US Environmental Protection Agency’s STORET database. Each voluminous report featured descriptive statistics and graphics of the parameters measured at each station, along with data on central tendencies and trends in annual, seasonal, and period-of-record water quality.42

The NBS/USGS-BRD had initiated vegetation mapping projects in 20 parks by 1998, with completed packages delivered to five. Vegetation mapping was a gargantuan job. The primary product of these efforts was a digital GIS layer of polygons showing the location of vegetation communities. The maps, however, were accompanied by an entire library of vegetation data and descriptive information, including a report, databases, geospatial datasets, photographs, and aerial photography. Project teams gathered aerial imagery, collected data from vegetation plots, classified and wrote descriptions of vegetation types, assessed the accuracy of the results, created the geodatabase and map, and wrote a report. Each project ultimately represented hundreds to thousands of hours of effort by ecologists, field technicians, GIS technicians, data managers, editors, and park staff.

Before the first projects even began, the NPS had to develop and adopt uniform vegetation classification standards in cooperation with other agencies and the Federal Geographic Data Committee’s Vegetation Subcommittee, and develop protocols for data collection and accuracy assessment. To test the classification system and field procedures, vegetation mapping was piloted at four ecologically diverse parks: Assateague Island National Seashore (MD/VA), Tuzigoot National Monument (AZ), Scotts Bluff National Monument (NE), and Great Smoky Mountains National Park (NC/TN).

Bailey’s ecoregions, on which vegetation mapping came to be based, and which served as the first foundation for the boundaries of monitoring networks.

To maximize efficient use of funds, vegetation mapping projects were clustered geographically, using a US Forest Service publication referred to as Bailey’s Ecoregions of the United States.43 Conducting the mapping at multiple parks in the same area during the same block of time (possibly using the same experts hired under the same contract), was expected to be cheaper, more effective, and more efficient than jumping from park to park according to the status of each park’s data.44 Originally published as a map in 1976, Bailey’s Ecoregions was expanded in 1980 to include narrative descriptions providing public land-management agencies with a more comprehensive understanding of ecosystems at the regional scale. It identified four broad “domains,” further broken into “divisions” and “provinces” based on climate, vegetation, and landform.45

After assigning each NPS unit to an ecoregion, the subcommittee calculated the number of high-priority vegetation mapping projects found in each ecoregion to determine the overall inventory order. As the greatest number of high-priority projects was found in eastern ecoregions, the top one-fifth of the list consisted almost entirely of parks near and east of the 100th meridian.46 In keeping with NPS recommendations, vegetation mapping officially began at smaller parks with predominantly prairie communities. The first finished projects were delivered to Devils Tower (WY), Jewel Cave (SD), Mount Rushmore (SD), and pilot parks Scotts Bluff (NE) and Tuzigoot (AZ). Because of the scale at which Alaska parks would be mapped, using satellite imagery instead of on-the-ground teams, vegetation mapping there was treated as a separate effort, coordinated by the Alaska Regional Office.47

All the early planning documents indicated the inventories would be completed in ten years’ time. But as the inventory process got underway, it quickly became apparent that the goal of completing 12 inventories for each of 250 parks (~3,000 inventories) in 10 years had been overambitious. Before work could begin there were standards, procedures, and agreements to develop and contractors to hire, and plans didn’t necessarily proceed according to schedule. Unused funds for some projects ended up pre-funding others, so while the wheels had started to turn, it took a while to get up to speed.

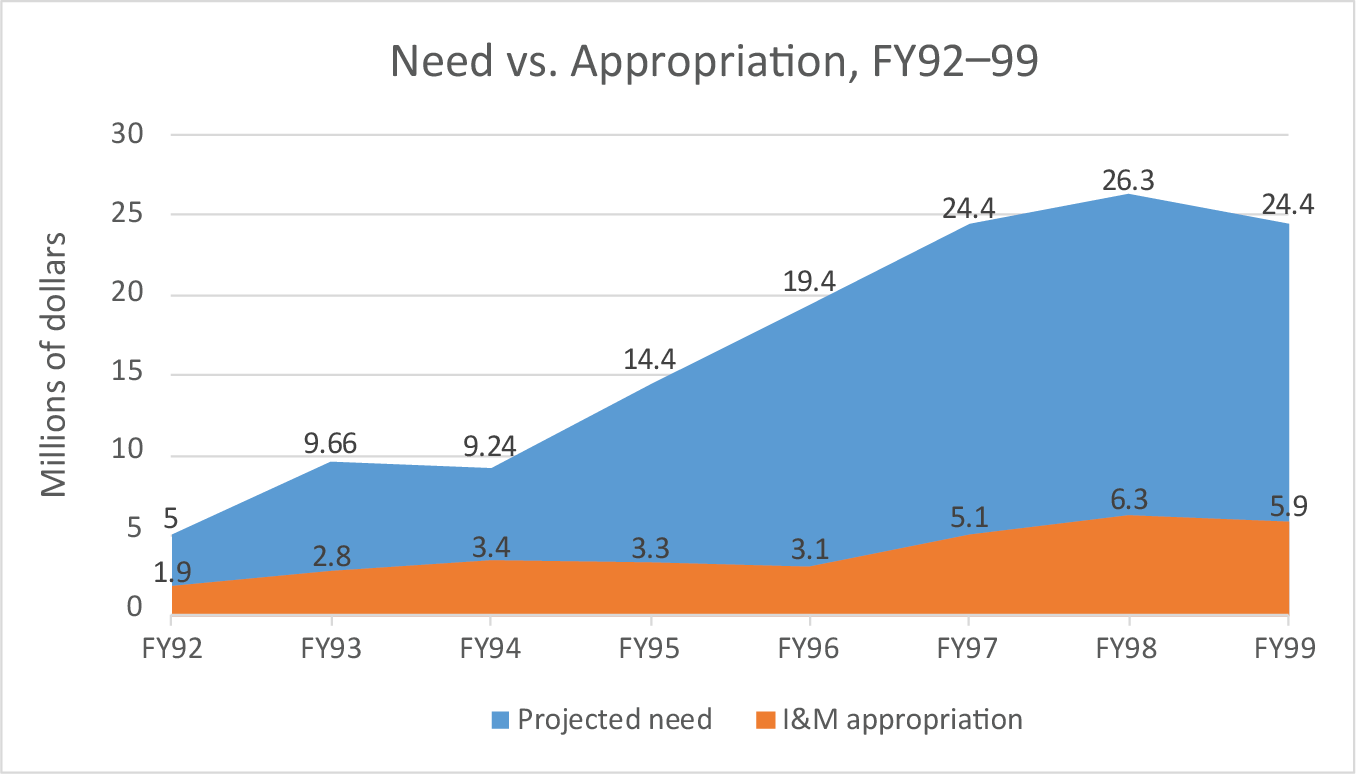

The bigger problem was funding. At its outset in 1992, the I&M program had a budget of $1.9 million. At that time, inventories were projected to cost about $109 million over 10 years, peaking at $17 million in fiscal year 1998.48 Since then, the program had received annual budget increases of $1–2 million in most years, with the total budget topping out at $6.3 million in fiscal year 1998—about 37% of the originally projected need for inventories alone that year (if they had been fully funded to that point). The result was that “the increases have not permitted the comprehensive inventories and monitoring that can effect the preservation of natural resources for future generations.”49

Projected need (ca. 1992) versus actual annual appropriations for the inventory and monitoring program, 1992–1999.50

In fiscal year 1998, no new vegetation mapping projects were started because there was only enough funding to continue the projects already underway. Another problem was a lack of control over how some of the money was spent. In fiscal year 1997, for instance, the USGS-BRD had used about $200,000 of funding intended for vegetation-mapping projects to pay salaries, instead, and I&M leadership was not confident they would be able to get the monies directed back to project work.51 By 1998, both BRD and NPS were planning to review the vegetation mapping program, recognizing that with flat budgets of around $1.1 million each year, the existing program was not sustainable. Program coordinator Mike Story predicted that at the current rate of funding and effort, vegetation mapping would drag on for the next 60 years.52

Lack of funding was also hampering efforts on the monitoring side of the program.53 By 1999, monitoring had been implemented at only three parks and clusters (Great Plains Prairie Cluster, Cape Cod National Seashore, Virgin Islands-South Florida Cluster) beyond the initial four. The other LTEM prototypes selected in 1993 (Northern Colorado Plateau Cluster, Mammoth Cave National Park, Olympic National Park, North Cascades National Park) were still waiting.

At the two funded cluster programs, it was increasingly apparent that passing the baton from the USGS-BRD to the NPS as the programs transitioned from research to operations wasn’t going to be as straightforward as previously imagined. Because protocols had to produce information useful to park managers and be achievable within the logistical and funding constraints of the eventual NPS-led program, there needed to be some level of NPS involvement during their development. For this reason, the Prairie Cluster had two coordinators: one employed by NBS, the other NPS. Because she alone didn’t necessarily possess all the necessary scientific expertise to be able to provide advice about the broad range of specialties the protocols addressed, NPS coordinator Lisa Thomas advocated for hiring the rest of the Prairie Cluster’s NPS staff over the course of three years prior to the end of the research phase.54 The LTEM staff, Thomas argued, would be “an essential bridge” between BRD scientists and park managers who, even before the transfer of scientists to the NBS, didn’t necessarily have access to natural resource specialists. This was especially true in smaller parks with a stronger focus on cultural, rather than natural resources, like those of the Prairie Cluster.

Just as they foresaw the need for NPS staff to participate in the research phase of the LTEM program, the leaders of the Prairie and Virgin Islands clusters recognized they would need access to BRD experts during the operational phase. Sooner or later, protocols would need to revised, and statistical analysis would need to be done on the data collected. Both clusters proposed a gradual, rather than abrupt, transition, in which NPS staff would be brought on prior to the actual transfer of funding and supervision from BRD to the NPS. They also advised Gary Williams that their programs would continue to need technical support from BRD for the foreseeable future. The Prairie Cluster anticipated needing an annual commitment of at least $50,000 for this assistance.

Neither cluster was confident it would be able to make the transition within the five years originally projected. For the Prairie Cluster, this was because five years was not expected to be enough time to develop and test protocols, identify levels of natural variability, and develop procedures for data management and reporting. The Virgin Islands cluster was behind schedule due to a lack of funding. Although its prototype proposal was written in anticipation of a $600,000 annual budget, the USGS-BRD had programmed just $175,000 for the Virgin Islands cluster in 1997 (its first year).55

Making the USGS partially responsible for an NPS program had turned out to be inefficient and ineffective on many fronts. Eventually, both the vegetation mapping projects and the entire monitoring program would be returned to the NPS—but not before the park service was given a mandate to do science, and the financial capacity to do it right. The two things NPS science proponents had sought for so long were about to change from wishes into reality. What would make the difference? For one thing, a story.

NEXT CHAPTER >>

<< PREVIOUS CHAPTER

Research and writing by Alice Wondrak Biel, Writer-Editor, National Park Service Inventory & Monitoring Division

1Inspector General to The Secretary, “Final Audit Report for Your Information - ‘Protection of Natural Resources, National Park Service,’” October 23, 1992.

2US Department of the Interior Office of Inspector General, “Audit Report: Protection of Natural Resources, National Park Service,” 5.

3US Department of the Interior Office of Inspector General, 12.

4Inspector General to The Secretary, “Final Audit Report for Your Information - ‘Protection of Natural Resources, National Park Service,’” October 23, 1992, 10.

5Inspector General to The Secretary, 10–11.

6Oddly, the OIG’s implication that everything that happened in a park except for resource management was “visitor-oriented” helped reinforce the perception—established in the Organic Act and institutionalized over the subsequent decades—that resource conservation and visitor enjoyment were mutually exclusive activities. They were seen as two sides of the same coin, cast in perpetual opposition to each other. Still today, the persistent notion that resource-protection activities have no direct impact on visitor experience is a constant challenge for resource managers seeking to fund their programs—even though the goal of such programs is to safeguard the very things that make up the core of visitor experience.

7It appears the I&M funds were indeed restored after the release of the OIG report. In a December information bulletin, Gary Williams stated that the FY1993 Servicewide I&M budget was $4.5 million. Williams, “I&M Information Bulletin.”

8National Research Council, Science and the National Parks, 93.

9National Research Council, Science and the National Parks, 96.

10Krahe, “Partners in Stewardship: An Administrative History of the Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit Network,” 18.

11Frederic H. Wagner, “Whatever Happened to the National Biological Survey?,” BioScience 49, no. 3 (March 1999): 219–222.

12“US Department of the Interior Secretarial Order No. 3173, Establishment of the National Biological Survey,” September 29, 1993, https://www.doi.gov/sites/doi.gov/files/elips/documents/archived-3173_-establishment_of_the_national_biological_survey.pdf.

13Diane Krahe, “The Ill-Fated NBS: A Historical Analysis of Bruce Babbitt’s Vision to Overhaul Interior Science,” in Rethinking Protected Areas in a Changing World: Proceedings of the 2011 George Wright Society Biennial Conference on Parks, Protected Areas, and Cultural Sites (George Wright Society, n.d.), 161.

14Wagner, “Whatever Happened to the National Biological Survey?”

15The Contract with America was a Republican legislative agenda introduced prior to the 1994 midterm elections. Rooted in the conviction that the federal government was “too big, too intrusive, and too easy with the public’s money,” it promised to reduce the size of government, lower taxes, slash welfare programs, and promote business interests.

16Davis, interview by Biel and Beer.

17Krahe, “Partners in Stewardship: An Administrative History of the Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit Network,” 18; Michael Soukup, interview by Alice Wondrak Biel, June 3, 2021.

18Michael Soukup, interview by Alice Wondrak Biel and Margaret Beer, December 10, 2019.

19“Science and Resources Management in the National Park Service,” 80.

20“Science and Resources Management in the National Park Service,” 80.

21Soukup, interview by Biel and Beer, December 10, 2019.

22Michael Soukup and Robert F. Doren, “Reorganization of the South Florida Research Center,” Park Science: A Resource Management Bulletin 13, no. 3 (Summer 1993): 1; Soukup, interview by Biel and Beer, December 10, 2019.

23“US Department of the Interior Secretarial Order No. 3173, Establishment of the National Biological Survey.”

24Williams, interview by Biel and Beer, November 20, 2019.

25National Park Service, “NPS Inventory and Monitoring Program Annual Administrative Report: Fiscal Year 1993,” 8; Davis, interview; Williams, interview, November 20, 2019; Gary Williams to Alice Wondrak Biel, “Manuscript Review,” October 14, 2021.

26National Park Service, “Inventory and Monitoring Program Annual Report: Fiscal Year 1996” (Fort Collins, Colorado: Natural Resource Information Division, 1997), 2.

27National Park Service, “Research in the National Park System.”

28Senate Hearings Before the Committee on Appropriations, Department Of the Interior and Related Agencies Appropriations, Fiscal Year 1988, 643–644.

29In 1999, Frederic Wagner observed that ironically, “if the net effect of the 1993–1998 changes is to increase the total research capability in DOI, the end result could be salutary.” Wagner, “Whatever Happened to the National Biological Survey? 221.”

30Krahe, “Partners in Stewardship: An Administrative History of the Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit Network,” 29; Soukup, interview by Biel and Beer, December 10, 2019.

31Soukup, interview by Biel and Beer, December 10, 2019.

32John Leshy to Secretary, “Secretary’s Authority for Creating the National Biological Survey,” May 2, 1994, https://doi.opengov.ibmcloud.com/sites/doi.opengov.ibmcloud.com/files/uploads/M-36980.pdf.

33Boudreau, “Synthesis and Evolution,” 12.

34Boudreau, "Synthesis and Evolution," 11–12.

35Boudreau, "Synthesis and Evolution," 11.

36Boudreau, "Synthesis and Evolution," 13.

37National Park Service, “Restructuring Plan for the National Park Service,” November 1994.

38Fort Collins was already home to the NPS Water Resources Division, and the GIS division and Air Quality Division were both located in Lakewood, so the move put I&M in close physical proximity to many of the agency’s other scientific professionals and potential partners.

39Williams, interview by Biel and Beer, June 10, 2020.

40Dennis B. Fenn to Regional Directors and Natural Resource Inventory and Monitoring Coordinators, “Servicewide Natural Resource Inventory Update and Projected Activities for FY 1994,” Memorandum, September 1993, http://npshistory.com/publications/interdisciplinary/im/im-activities-fy1994.pdf. The list would undergo some revisions in 1997, after “increased urgency for inventories in some parks; the completion of many inventories;” new opportunities for leveraging funds; and “the need for more explicit information about the execution of biotic surveys and geologic inventories” prompted Rich Gregory to ask park superintendents to re-evaluate their priorities. Rich Gregory to Superintendents, Natural Resource Park Units, “I&M Program Priorities for Natural Resource Inventories,” Memorandum, July 30, 1996, Folder, “Priority Call 1996,” IMD Chief’s Office; Gary Williams to Files, “Priority Listings for Level I Inventories,” July 22, 1997, Folder, “Priority Call 1996,” IMD Chief’s Office.

41Williams, interview by Biel and Beer, November 20, 2019.

42National Park Service, “Inventory and Monitoring Program Annual Report: Fiscal Year 1998” (Fort Collins, Colorado: Natural Resource Information Division, 1999), 17; Water Resources Division and Servicewide Inventory and Monitoring Program, “Baseline Water Quality Data Inventory and Analysis: Mojave National Preserve,” Technical Report (Fort Collins, Colorado: National Park Service, October 2001).

43Fenn to Regional Directors and Natural Resource Inventory and Monitoring Coordinators, “Servicewide Natural Resource Inventory Update and Projected Activities for FY 1994,” September 1993.

44Williams, interview by Biel and Beer, November 20, 2019.

45Robert G. Bailey, “Description of the Ecoregions of the United States,” Miscellaneous Publication (US Department of Agriculture, 1980), https://www.fws.gov/wetlands/Documents/Description-of-the-Ecoregions-of-the-United-States.pdf.

46Fenn to Regional Directors and Natural Resource Inventory and Monitoring Coordinators, “Servicewide Natural Resource Inventory Update and Projected Activities for FY 1994,” September 1993.

47National Park Service, “Inventory and Monitoring Program Annual Report: Fiscal Year 1997” (Fort Collins, Colorado: Natural Resource Information Division, 1998).

48Williams, “Phase I Overview”; National Park Service, “Inventory and Monitoring Program.”

49National Park Service, “Inventory and Monitoring Program Annual Report: Fiscal Year 1997,” ix. As of November 2018, vegetation mapping inventories were still ongoing, with the last 47 projects in progress. https://www.nps.gov/im/vmi-products.htm.

50“History of Inventory and Monitoring Funding,” 1999, Office of the Chief, Inventory and Monitoring Division, Fort Collins, Colorado; Williams, “Phase I Overview.”

51“Summary, NPS National I&M Advisory Committee Meeting, Jacksonville, Florida” (NPS National I&M Advisory Committee Meeting, Jacksonville, Florida, 1997).

52“Summary, NPS National I&M Advisory Committee Meeting, Seattle, Washington” (NPS National I&M Advisory Committee Meeting, Seattle, Washington, 1998); “Meeting Notes” (Springfield, Missouri, 1998).

53“Inventory and Prototype Monitoring of Natural Resources in Selected National Park System Units, 1998-1999,” Natural Resource Technical Report (Fort Collins, Colorado: National Park Service, Natural Resource Information Division, 2000); National Park Service, “Inventory and Monitoring Program Annual Report: Fiscal Year 1996.”

54Lisa Thomas to Gary Williams, “Transition Plan,” June 24, 1997, Inventory & Monitoring Division, Ft. Collins, Colorado.

55“Inventory and Monitoring Protocol Development - Operational Program: A Plan for Transition, Virgin Islands/South Florida Cluster,” n.d., Inventory & Monitoring Division, Ft. Collins, Colorado.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Tags

Last updated: September 25, 2023